Jason Hill, Brett Sandercock (Kansas State University), and Clay Graham prepare to relase an Upland Sandpiper wearing a solar-powered GPS tag at Konza Prairie, Kansas. © Jason Hill

Tracking grassland birds with satellite tags is all about understanding their year-round movements. And it’s also about connecting people and lands along the bird’s migratory path.

We often think about the conservation of migratory birds primarily as management actions aimed at promoting and enhancing breeding efforts. However, many migratory bird species, like the Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda), spend only 4 to 5 months on the breeding grounds. Yet, for the vast majority of bird species, we know far more about their breeding biology, than their migration and over-wintering ecology. In many ways this discrepancy is understandable—during the breeding season birds tend to be easier to find (e.g., they frequently vocalize and have brighter plumage), and (in the U.S. especially) their breeding locations are often well-documented.

But once the breeding season ends, the mystery begins for many bird species that are on the move.

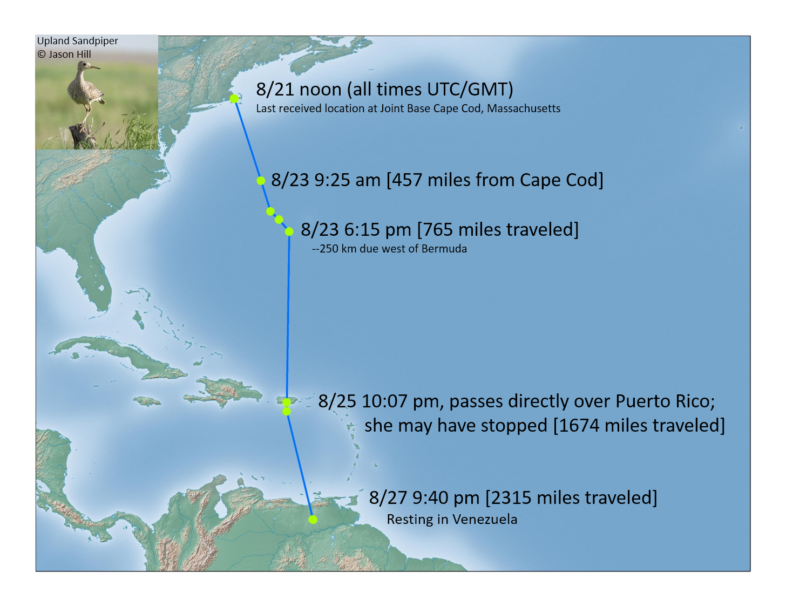

In May, we attached a solar-powered satellite tag to an Upland Sandpiper at Joint Base Cape Cod, MA, as part of our grassland bird research and partnership with the DoD Legacy Program. In late August, this female sandpiper took off from Cape Cod and spent four days flying south across the Atlantic, over Puerto Rico, and on to Venezuela, where she has been taking a well-deserved rest of the last two weeks. Eventually, she’ll likely continue her journey to southern South America, perhaps Argentina.

There is much that we want to know and document about her journey. What type of habitat is she using along the way? Are these stop-over areas rangelands or natural grasslands vulnerable to agricultural conversion? Are these areas protected, and are they important to other species besides Upland Sandpipers? And many more.

Since she landed in Venezuela we have been in touch with almost half a dozen colleagues there who are helping us answer these questions. With a little luck, we’ll be able to identify these stop-over habitats and the people that own them, and string together a safe network of lands stretching from the breeding grounds to their wintering areas.

The trans-Atlantic flight of an Upland Sandpiper during autumn migration.