Here in Vermont, we dream of June during the darkest days of January. Verdant wooded hillsides glowing brightly under a robin egg sky. Warm afternoon breezes rolling through the valleys as we lounge by the clear waters of a cold river. The chorus of birds waking us each morning. The smell of freshly cut grass wafting through the window. We forget about the clouds of black flies, the hum of the mosquitos and the rainy days. June is a dream here. Its days last forever.

By Desiree Narango

When you think of moths, what colors come to mind? Gray? Brown? What about hot pink and electric yellow? This June, your porch light may come alive with the disco party colors of a charismatic nocturnal visitor that epitomizes the word ‘cute’: the Rosy Maple Moth (Dryocampa rubicunda). June marks the peak flight of adult Rosy Maples, which come out to find a mate and lay eggs in late June.

Rosy Maple Moths are also called Green-striped Mapleworms due to their equally adorable caterpillar stage. To complete their life cycle, Rosy Maple Moth caterpillars feed almost exclusively on maple trees. They are what entomologists call a ‘specialist’ insect–one dependent on just a small number of host plants to complete its life cycle. Vermont is home to seven species of native maple trees, and numerous introduced non-native species. Yet, despite the availability of a diverse menu, these caterpillars tend to favor the sweetest members of the Acer genus, Sugar Maple (A. saccharum) and Red Maple (A. rubrum). So those local sugarbushes not only yield syrup for your pancakes, they also support a vast amount of native wildlife. Despite being very closely related to our native maples, non-native maples like Norway Maple (A. platanoides) and Japanese Maple (A. japonicum) are subpar cuisine and tend to be avoided by most insects that specialize on maples.

Adult Rosy Maples do not feed, meaning the entirety of their life cycle depends on the availability of maple trees. Don’t worry though–tree herbivory from Rosy Maple caterpillars is usually minor, especially in New England where this species has only one brood a year. Trees bounce back in no time, suffering no lasting damage from briefly hosting this insect.

You may never even notice if your backyard maple tree is hosting mapleworms. But if you do find caterpillars, consider sharing your observation with us on our iNaturalist Caterpillar and Sawfly Host Plant Project. Your observations will help illuminate patterns of host plant selection by butterflies and moths across the region.

Rosy Maple Moths can be found in most deciduous and mixed-forests across Vermont, even in residential neighborhoods. And there are a variety of ways to help support moth populations.

Happy mothing!

By Jason Hill

Awash in newly arrived birds, June is an easy time to miss the appearance of one of my favorite giants: Trichiosoma triangulum, the Giant Birch Sawfly. Adults emerge in late May in New England, after overwintering as cocooned larvae buried in the leaf litter. Once transformation to their adult stage is complete, they chew a hole in their cocoons and escape to freedom.

In contrast to most sawflies, this species is large, conspicuous, and easy to identify. The other 100,000+ species of described sawflies (Suborder Symphyta) are notoriously difficult to identify. It doesn’t help that the taxonomy of sawflies (and the closely related horntails and wood wasps) is constantly in flux. Like other sawflies, however,T. triangulum is a stingless species that (likely) feeds on pollen and nectar; the details of their diet are not well documented. Stingless they may be, but their powerful mandibles (especially enlarged on males) can deliver a most uncomfortable bite if handled on anything but very chilly days.

The adults may feed on tree sap, as well, using those large mandibles to girdle small branches. Female T. triangulum deposit eggs in late May or June inside the leaves of alder (Alnus), birch (Betula), Willows (Salix), and other shrubs and trees. The females insert their ovipositor just beneath the cuticle of a leaf, and use a saw-like motion to create a cavity for the deposited egg. Larval T. triangulum superficially resemble caterpillars, defoliate plant leaves, and can ‘reflex bleed’ to deter predators by excreting a clear defensive liquid. By the end of the summer, the larva drop to the ground where they build a cocoon for the winter. T. triangulum is widespread throughout northern New England from sea level to mountain summits, but is infrequently photographed and reported. Having seen folks run from these amazing (and harmless) sawflies atop Killington Peak, Vermont, I suspect their size and appearance discourages many would-be-photographers.

By Michael Hallworth

The northern forest is teeming with life this time of year, when black flies, mosquitoes, and caterpillars are plentiful. The flush of insects is precisely why millions of songbirds migrate thousands of miles from the tropics to breed in this region. They’re taking full advantage of the insect buffet. The abundance of food is especially important for female songbirds as they enter an energetically demanding time of the year: egg laying. Typically, female warblers lay one egg a day and, depending on the species, lay between four and five eggs per nest. The lucky ones build a nest, lay eggs, raise nestlings, and are finished breeding for the year. Some even produce two broods. Others aren’t so lucky. Why? Chipmunks, Red Squirrels, Blue Jays, Black Bears, and the occasional White-tailed Deer can’t resist the tasty, protein-rich eggs or vulnerable nestlings.

Nest predation varies from year to year; in some years there aren’t many predators, but in others predators can nearly bring songbird reproduction to a standstill. In summers following a heavy cone mast, when Red Squirrels and Chipmunks are abundant, nest predation is high and female songbirds have their work cut out for them. Since songbirds are relatively short-lived and may only have a single breeding season to raise young, they’ll continue to re-nest as long as enough food is in the forest. For example, the summer of 2007, which followed a year of abundant cones, was an especially rough season for female Black-throated Blue Warblers. One laid 18 eggs in a single season! Despite her best efforts, she failed to fledge any young. So next time you’re walking in the woods and enjoying all the beautiful songs that males sing, be sure to tip your hat to all the hard-working females.

By Kent McFarland

The Northeast is home to over 40 species of blackflies, although only four or five are considered really annoying to humans. In some cases, blackflies may not bite but merely irritate us as they swarm about. (Hint: they like dark objects so choose clothing wisely.) Only the females bite and fortunately for us, most species feed on birds or other animals.

Biologists have found Peregrine Falcon chicks being killed by recent outbreaks of blackfly swarms in the Arctic, possibly due to climate change. Farther south in Wyoming, researchers found blackflies killed 14% of the Red-tailed Hawk nestlings that they monitored, and they were the only known cause of mortality. In 1984, heavy spring rains in the Upper Midwest apparently created ideal breeding habitat for blackflies, whose populations exploded. Dense clouds of them attacked nesting Purple Martins, causing widespread die-offs and colony-site abandonments. Blackflies can be a big problem for many nesting birds.

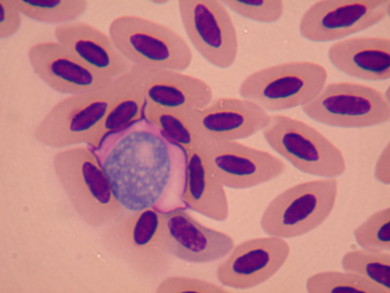

A stained blood smear showing Leucocytozoon (large purple blob) among Bicknell’s Thrush blood cells / © VCE

But they don’t just bite birds, they also transmit disease. Leucocytozoon is a genus of parasitic protozoa. They use Simulium blackfly species as their definitive host and birds as their intermediate host. There are over 100 Leucocytozoon species and more than 100 species of birds have been recorded as hosts.

VCE teamed up with University of Vermont biologist Ellen Martinsen and found that in Vermont’s Green Mountains, 67% of females and 48% of males were infected by Leucocytozoon spp. Our colleagues in New Brunswick, Canada found that 69% of the Bicknell’s Thrushes they sampled were parasitized by Leucocytozoon.

Blackflies breed exclusively in running water. Some species live in large, fast-flowing streams, others in small, sluggish rivulets. Almost any kind of permanent or semi-permanent stream is occupied by some species. Large blackfly populations indicate clean, healthy streams since most species will not tolerate pollution.

Blackfly females lay their eggs on vegetation in streams or scattered over the water surface. The eggs hatch in water and larvae attach to submerged substrate. They feed by filtering water for tiny bits of organic matter. Once the larvae are mature, they pupate underwater. Emerging adults ride bubbles of air, like a hot air balloon, to the surface and fly away. They mate nearby and females search for a blood meal before laying eggs.

By Bryan Pfeiffer

Even devoted birdwatchers find it tough to love the Brown-headed Cowbird. Black body. Fat head. Grating voice. And the female is a homely gray. Not exactly a glamor couple. But appearance is only part of the cowbird’s PR problem.

What most disturbs some birders is cowbird breeding behavior, which biologists call “brood parasitism.” Cowbirds build no nests of their own. After having indiscriminate sex, females wander the landscape laying eggs in the nests of other songbirds, leaving the unwitting foster parents to raise the cowbird chicks.

This doesn’t always turn out so well for the host family. Cowbird chicks exercise brutal sibling rivalry. They tend to grow faster and larger than their adoptive siblings, gaining an edge in gobbling the food delivered by parents. During the melee at feeding time, cowbird chicks might stomp on and smother nest mates. They sometimes even push eggs or chicks out of the nest.

The most poignant evidence of all this comes after the cowbird fledges. Birders occasionally encounter an elegant songbird–a northern cardinal, a chipping sparrow, or a yellow warbler, for example–feeding a hulking cowbird chick out of the nest. It’s like a human mom with triplets feeding a fourth who happens to be an NFL linebacker.

But let’s give cowbirds their due. After all, cowbirds are simply being cowbirds. Like the rest of us they’ve adapted to changes in the landscape. Read more in an essay from VCE Research Associate Bryan Pfeiffer published in Northern Woodlands magazine.

By Kent McFarland

Have you ever seen a large bee hovering around you like they are about to attack? And then suddenly they zoom off? This is common behavior for male Eastern Carpenter Bees as they patrol their small territories looking for intruders or mates. There’s no reason to be alarmed; males don’t sting. Only the dark-faced females can muster a sting, and usually only if handled. Male territories encompass about 60 feet around the nest site or food-plant area, and they will chase any interloper that comes near–birds, flying insects, people, and even, reportedly, the occasional airplane high in the sky.

There are over 300 species of native bees in Vermont, but there’s only one large carpenter bee, the Eastern Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa virginica), and it’s fairly easy to identify. At first blush they look like large bumble bees, but if you look more closely you’ll notice that they have shiny, black, and hairless abdomens. Peer even closer and you’ll see massive and sharp appendages, called galea, hanging down from the mouth. These are used to chew their way through wood, giving them their name.

Carpenter bees don’t eat wood. They gnaw through it, creating tunnels for nesting and resting in dead trees or branches, logs, or unfinished wood on structures. They prefer softwoods like pine, fir, or cedar, which are easier to excavate. With their sharp galea, a female chews a round entrance hole about a half-inch in diameter. It can take her up to two days to chew across the wood grain. Once the tunnel is about as deep as the length of her body, she turns 90 degrees and excavates more quickly going with the grain. If she comes to a knot, she’ll tunnel around it. Some nests have two or more tunnels that parallel the main hall, each over a foot long. They can use the same nest site year after year, sometimes by adding a new tunnel or lengthening an existing one. One studied colony was used for 14 years.

Carpenter bees are so-called solitary bees. Unlike honey bees or most bumble bees, there are no queens or workers, just individual males and females. Newly hatched females may live together in the nest with their mother during their first year, but after that each female will have its own nest and brood.

At the end of a tunnel, the female lays an egg on a loaf of pollen the size of a kidney bean. At just over half an inch, it’s one of the largest insect eggs in the world. The female chews the surrounding wood into a pulp to create a cardboard-like partition that seals the egg within its own cell. Each tunnel can have up to eight cells. When they hatch, the grubs feed on the loaf of pollen.

Here’s what gets them in trouble. Carpenter bees can create nests in fences, outdoor furniture, and buildings. They select bare wood on roof eaves, fascia boards, porch ceilings, decks, railings, siding, and shutters. They will seldom bore into painted or varnished wood.

It takes years for carpenter bees to cause significant structural damage. You can minimize their damage by filling and sealing nest holes in the fall or winter with a small dowel or caulk and covering them with fresh paint. Filling them in the spring or summer will just cause the female to make a new entrance hole. You can also provide alternative nesting sites in untreated cedar boards, their favorite wood.

Why not just eradicate them? Carpenter bees pollinate plants in 19 different families, from spring lupines to late-summer goldenrods. Like most bees, they enter the opening of a flower and reach in with their glossa, like a long tubular tongue, to suck nectar. They also gather pollen to carry away on their bristled-covered rear legs.

Carpenter bees are also cheaters. If the flower is too small or too long for them to reach with their relatively short glossa, they put their carpenter’s skill to work and simply cut a hole into the base of the flower for direct access to the nectar. Other bees will also sometimes feed at these nectar holes as well.

Over the last decade, carpenter bees have been moving farther and farther north. Keep watch for the hovering male signaling his territory around you and add your sightings to the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist! Check out the map of sightings and see if any have been observed near you.

Thank you so much for explaining more about creatures I’ve heard about but knew little about and for the links and, of course, the great photos.

I’m too lazy and busy to read it ALL, but loved the pictures and the information about cowbirds. Thanks!

Wonderful information. I hiked with Michael Sargent today. He said his photography that was credit had a link. Can’t find?