An owl print in the snow. / © K.P. McFarland

This month, wildlife and the rest of us here in New England will cross a threshold – arbitrary yet not insignificant: 10 hours of daylight. You can sense it when you head out in the morning: Black-capped Chickadees, Northern Cardinals and European Starlings are among birds breaking out into song, and Downy Woodpeckers are starting to drum. Even though we’ve got lots more winter, we’ve also got change. So here’s a Field Guide to February to help get your hopes up, no matter what that groundhog predicts.

February In flight

Some of the notable birds seen around Vermont during the past few weeks: Bohemian Waxwings (view eBird map) have begun to join Cedar Waxwings feeding on wild fruit and ornamental trees, even in our cities. We’re also seeing a few Pine Siskins (view eBird map) coming to feeders around the state.

Pick your favorite sign of spring: squirrels mating, mud oozing, maples flowering. We like a vulture soaring. Although it’s hardly a long-distance migrant, Turkey Vulture is among the first northbound birds we see (view live eBird map) in northern New England each February. Not far behind are Red-winged Blackbirds (view live eBird map). We hope you’ll add your sightings to eBird.

Check out the eBird bar chart for this month to find out what might be around you this month.

Leap Day 2016

Since it takes the earth 365 days, 5 hours, and 48 minutes to circle round the sun, a Leap Year with one “extra day” every four years is an adjustment that keeps our calendar in synchrony with the planetary cycle. The good news is, you have an extra day to work on your bird life list this year!

Since it takes the earth 365 days, 5 hours, and 48 minutes to circle round the sun, a Leap Year with one “extra day” every four years is an adjustment that keeps our calendar in synchrony with the planetary cycle. The good news is, you have an extra day to work on your bird life list this year!

Playing ‘Possum

The Virginia Opossum has its first litter of 5-13 young in February. The young are about the size of a bumble bee at birth, only one-fifth of a gram. As soon as they are born they crawl, blind, into the female’s pouch and begin to nurse. After 60 days of pouch life, they crawl out and may be carried on her back. When they are about 100 days old, they are on their own.

With thin fur coats, naked tail, and ears and a long snout; opossums are not well adapted to a cold northern winter. Many show signs of frostbite. Yet, they have be marching slowly northward in overall distribution for decades. The first opossum was reported in Burlington in 1988. By 1995, they had reached Montreal.

“They are very opportunistic, and my guess is that global warming has something to do with pushing them farther north,” University of Vermont mammalogist Bill Kirkpatrick told the Burlington Free Press in 2000.

With a mild winter so far, opossums are likely to continue this trend. You can help track their range by posting your sightings to iNaturalist Vermont. Meanwhile, check out the latest sightings reported from around the state.

Nesting Owls

Despite the cold and snow, here in the north breeding season for Great Horned Owls is underway. They’re already sitting on their nests in the southeast. Pairs may roost together near their chosen site before the female lays eggs, which will hatch in just over a month. Listen for them in your neighborhood. Even though the female is larger than her mate, the male has a larger voice box and a deeper voice. Pairs often call together. You can often hear the differences in pitch. Great Horned Owls use old nests of other species, usually Red-tailed Hawks, other hawk species, crows, ravens, herons, or even squirrels. They may line the nest with shreds of bark, leaves, downy feathers plucked from their own breast, fur or feathers from prey, or trampled pellets. Nests deteriorate over the course of the breeding season, and are seldom reused in later years.

If you hear or see a Great Horned Owl, add your sighting to eBird. Here’s a map of all the sightings reported so far this year.

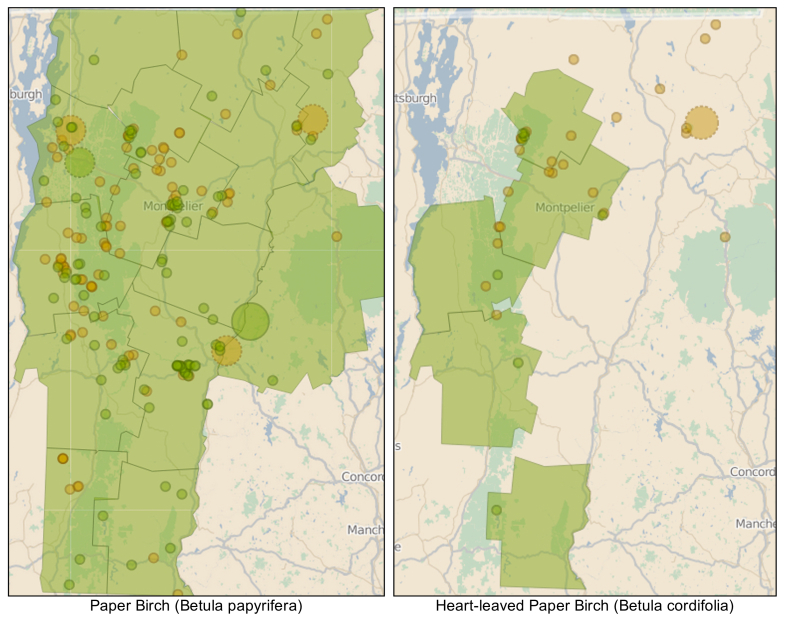

segregation BY elevation: Paper Birches

Many people don’t realize that two species of paper birch trees grow in northeastern North America – Paper or White Birch (Betula papyrifera) and Heart-leaved Paper Birch (B. cordifolia), once considered a variety of White Birch. As its name suggests, the latter species has distinctive heart-shaped, many-veined leaves, and it is restricted to mid- to high-elevation Appalachian and northern forests.

Many people don’t realize that two species of paper birch trees grow in northeastern North America – Paper or White Birch (Betula papyrifera) and Heart-leaved Paper Birch (B. cordifolia), once considered a variety of White Birch. As its name suggests, the latter species has distinctive heart-shaped, many-veined leaves, and it is restricted to mid- to high-elevation Appalachian and northern forests.

Heart-leaved Paper Birch is a diploid (28 chromosomes), making it unlikely that these two species will readily hybridize. The primary means of distinguishing Heart-leaved Paper Birch from White Birch include:

- The leaf base is heart-shaped (cordate).

- Its leaves are dotted with resin glands.

- Young shoots are not hairy.

- A bronze or pinkish inner bark shows when the outer bark peels.

We know surprisingly little about the exact range of these two species. How low in elevation does Heart-leaved Paper Birch grow? How high does White Birch climb into the mountains? Do they overlap in some areas? And how will these species respond to climate change, or have they already? Observers adding records to iNaturalist Vermont, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life, are helping to map these and many other species. We hope you will add your observations too.