Last year we announced an exciting new web site that allowed us to connect with volunteers the the virtual internet world to help us enter thousands of historic bird records that only existed on paper and filed away in boxes. We called it the Phoenix Project, part of the Vermont Atlas of Life. Many of you answered our call for help. Volunteers joined our virtual expedition and digitized nearly 6,000 pages of historic spring bird records in just 3 months! Now we need your help with our second virtual expedition.

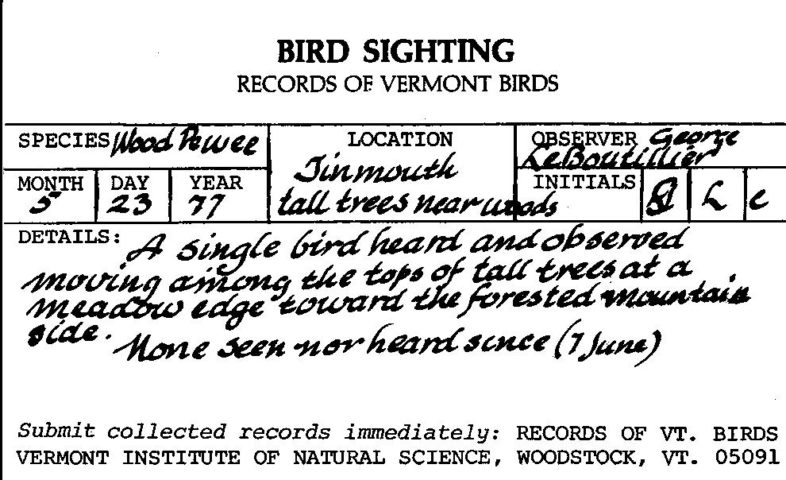

We’ve scanned over 7,000 spring bird observation cards spanning from 1974 to 1999 and uploaded them for data entry. These bird sightings were from a paper publication many of you may fondly remember: Records of Vermont Birds (RVB). For 30 years, RVB was the most complete and authoritative source of bird sightings, including first arrival dates for migrants, ever assembled — on paper. RVB’s publisher, the Vermont Institute of Natural Science, has given to VCE the historic bird records behind RVB. With your help, we will bring that data online.

An historic bird observation card from the Records of Vermont Birds.

The rebirth of bird sightings data depends on a dedicated corps of volunteers who, in their leisure time and from the comfort of home, can easily move bird sightings from paper to computer. To make it happen, VCE traveled virtually around the world to Australia to team up with DigiVol. DigiVol is a crowdsourcing platform that was developed by the Australian Museum in collaboration with the Atlas of Living Australia and is used by many institutions around the world as a way of combining the efforts of many volunteers to help digitize important biodiversity data. DigiVol allows volunteers to view scans of the paper documents online, and convert them on the spot to digital form. From there, VCE verifies the data entry and then adds the records to Vermont eBird, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life, for use free of charge to anyone — from students to birders to researchers.

Here at VCE, we’re ready to put some of the digitized data to use. Since much of those early bird sightings were first collected, the growing season in Vermont has increased by about two weeks. Ice-out on lakes and leaf-out on the lilacs in our front yards come about 12 days sooner. Although the phenology — or the timing of major natural events — varies normally from year to year, on average Vermont springs come earlier. And that could be a concern for bird conservation. As plants and insects emerge earlier in the season, for example, we can analyze whether birds have adequately adjusted the timing of their own migration or breeding cycles to keep pace. A mismatch could cause bird populations to decline.

Visit our DigiVol project where you can register and login. You’ll find a short tutorial to read before getting started. If you have questions or would like to share a neat observation you uncover during your travels through these historic records, there’s even a project forum to post notes to the community, ask us questions if you need help, or even just note a neat historic record you’ve encountered that others might want to hear about.

With the help of volunteers distributed literally around the world many hands will make light work of science and conservation. Thank you to those of you that have helped us with this massive task in the past, and those of you joining us on this new mission.