Mount Mansfield after a late autumn snow shower. / © K.P. McFarland

October is a month of change. The leaves slip from green to gold. Then, suddenly, they all seem to drift to the ground. The trees are nearly naked once again, and ‘stick season’ has arrived. So, here’s your field guide to some moments that you might not otherwise notice during these few precious weeks that feature yellow-brown hills beneath a deep blue sky (with the last Monarchs fluttering southward).

Some Sharpies Go South

Sharp-shinned Hawk about to be released after it was banded and a sample of blood taken for analysis of mercury levels. / © K.P. McFarland

The autumn river of raptors migrating southward becomes dominated by Accipiters like Sharp-shinned Hawks in October. Although not all individuals leave, many do. More than 11,000 Sharp-shinned Hawks were seen on one October day at Cape May Point, New Jersey as they pushed southward. Most overwinter somewhere in North America; however, some travel as far south as Central America, migrating thousands of miles between their breeding and wintering grounds. They are powered by a mix of flap-gliding flight and soaring on mountain updrafts and rising plumes of hot air. Recently, more sharpies have been overwintering farther north. No one knows exactly why, but the popularity of backyard bird feeding may provide some Sharp-shinned Hawks the food they need to survive northern winters.

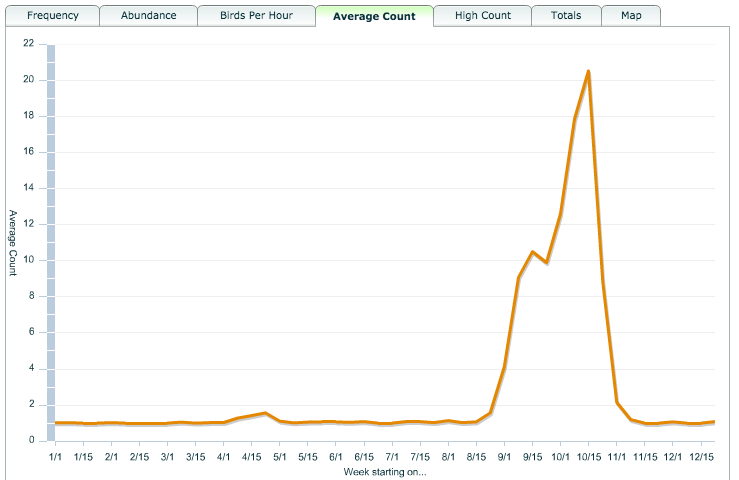

Observations of Sharp-shinned Hawks reported to Vermont eBird. You can help track these and other birds by reporting your sightings too.

Sharp-shinned Hawk populations currently appear stable, after dramatic declines during the DDT pesticide era (mid-1940s to 1972). Recently, work by VCE has shown that individuals nesting in Vermont’s Green Mountains and a rare subspecies in the mountains of Hispaniola, have high levels of mercury in their blood. Learn more from VCE’s Research Notes about this finding.

The Phenology of Fall Leaves

Autumn view from Okemo Mountain fire tower. /© K.P. McFarland

We’ve all learned the basics of how and why leaves change color in the fall. But on this edition of Outdoor Radio, we take a deeper look at the chemistry of fall foliage and take leaf peeping to a whole new level. We meet Joshua Halman, a Forest Health Specialist with the Vermont Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation at Underhill State Park, where a fresh autumn snow has fallen overnight. The department has monitored these trees for 25 years, recording color change and leaf drop here and at other places around the state.

Halman reports that this work has documented the impacts of climate change. “Seen over this time, the peak color and the main time for leaf drop has actually become later,” Halman explains. “What we’re seeing since we started recording our fall phenology data is that, on average, foliage is peaking about eight days later over that 25-year period.”

Listen to the show

You can find more information at the Vermont Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation’s Forest Health Monitoring page, and learn more about fall leaves on the VCE blog – Turn Red or You’re Dead and Abscission and Marcescence in the Woods.

The Last Butterflies?

A Clouded Sulphur sips from a Dandelion flower. / © K.P. McFarland

For the past eight months they have flickered and fluttered among us – tiny flashes of red, orange, yellow and blue floating above hayfields and dancing in flower gardens: Spring Azures, Great Spangled Fritillaries, Red Admirals, Monarchs and more than a hundred other butterfly species here in New England. But soon, when freezing temperatures finally reach the warmest corners, the show will come to an end. Our last butterfly of the year, probably a Clouded Sulphur somewhere, will flutter no more. Winter will finish off the butterfly season.

Or so we’re told. Even in the deepest, darkest winter night, they’re among us. Learn more on the VCE blog… and add your sightings to our site, e-Butterfly.org.

Long Live the Queen!

Northern Amber Bumble Bee nectaring Red Clover. / © K.P. McFarland

Most of the bumble bees you see flying right now are males (drones) looking for a mate or young queens preparing for winter. Each year in the bumble bee kingdom, only a queen will carry the colony’s torch through winter to produce the next generation. Every other bee – workers, drones, and the old queen – dies with the onset of fall frost.

Not so with the honeybee, with which more people are familiar. In the dead of winter, you can visit the honeybee observation hive at the Montshire Museum of Science, which is made with a pane of glass on each side of a thin box. The workers are all gathered around the queen in one spot. If you put your hand on the glass away from them, the glass is frigid, but the back of your hand on the glass right in the center of the cluster is incredibly warm. Eating stored honey keeps their metabolisms high enough to produce excess heat and keep the cluster alive.

Bumble bees take a completely different approach. They do not put all of their energy into food storage for the winter but hedge their bet on the survival of a few queens. Read more on the VCE blog… and add your photo-observations of bumble bees to iNaturalist Vermont.

Going Deep

Spotted Salamander.

In the spring Spotted and Jefferson’s salamanders crawl to vernal pools — temporary woodland ponds that fill with water but then dry out later in the summer, providing a fishless environment for larval salamanders, where they mate and lay eggs. But for 90% of the year, these salamanders are elsewhere in the forest. Sometimes you can find them by flipping over a large stone or rolling a rotting log, but for the most part, they are tough to find.

Technology allowed VCE biologist Steve Faccio to easily spy on salamanders using miniature tags that emit a radio signal. With a radio receiver and small antenna, Steve could then monitor each tagged salamander’s movements and locations.

Standing on a forest path near the site, Steve turned on his radio receiver and tuned to a salamander’s frequency. A faint, but audible “ping” sounded from the headphones. A few minutes later Steve had honed in to the general area of the animal. The signal was strong, but he couldn’t quite pinpoint it. The salamander was underground.

After an hour on hands and knees, Steve found the exact spot. A series of narrow, branching tunnels under the leaf litter and rotting logs held the prize. Steve was able to move just a few leaves and there it was peering out from a tunnel opening.

These salamanders can’t dig. They use shrew, mice and chipmunk tunnels for refuge. In fact, the tunnels are so important to them that Steve could predict areas in the forest that would be used by the salamanders just by the density of mammal tunnels. Without small mammals, there were no salamanders to be found.

After tracking them to these surface tunnels all summer long, suddenly, with the chill of fall, the salamanders changed behavior. They entered more vertical tunnels that led deeper underground. By November nearly all of them were deep under the earth. The radio signal only traveled about two or three feet, so eventually the signals were lost. They had gone deep enough to escape the ground-penetrating frost, and radio spying by biologists from above.

Nice photos…….nice article

Interesting article! October is such an exciting month with so many changes happening.