Here in Vermont, we dream of June during the darkest days of winter. Verdant wooded hillsides glowing brightly under a robin egg sky. Warm afternoon breezes rolling through the valleys as we lounge by the clear waters of a cold lake. The chorus of birds waking us each morning. Butterflies and bees skipping from one flower to the next. We often forget about the clouds of black flies, the hum of the mosquitoes and the rainy days. June is a dream here. Its days last forever. Here are some natural history wonders for the month from the Green Mountains.

Black Flies Bother Birds too

We are not alone in complaining about black flies. Our loon biologists and volunteers are experiencing denser than average black fly swarms this year. Recently, they were particularly bad on Maidstone Lake. A new volunteer, Becky Scott, met up with VCE’s loon biologist, Eric Hanson, to deploy loon nest warning signs around an island.

As they approached the island, they observed the pair in the channel near the traditional nest site and assumed they were likely not nesting yet, but definitely thinking about it. Eric took a peek at the nest site that the pair has used most frequently in the past and saw two eggs covered with black flies. The loon was off the nest because of these pesky flies.

In Wisconsin, biologists have estimated that during year with high populations of black flies, nearly 50 percent of the loon nests fail. Usually these failures occur early in the nesting cycle and the majority of the loon pairs re-nest.

The Northeast is home to over 40 species of black flies. But only 4 or 5 are considered to be really annoying to humans. In some cases, black flies may not bite but merely annoy us, as they swarm about our head or body (Hint – they like dark objects. Choose clothing wisely). Only the females bite and fortunately, for us, most species feed on birds or other animals. There is one species of black fly that feeds exclusively on loons, so the black flies attacking us are likely a different species than those biting loons.

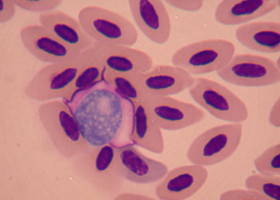

They don’t just bite birds, they can also transmit disease. Leucocytozoon is a genus of parasitic protozoa. They use Simulium black fly species as their definitive host and birds as their intermediate host. There are over 100 species and more than 100 species of birds have been recorded as hosts, including loons. And it may compromise their overall health.

Back on Maidstone Lake, Becky observed that the pair remained off the nest throughout Memorial Day weekend, indicating that the nest will likely fail. There are still several weeks for the pair to re-nest after the black flies subside. Eric has noticed many pairs this year near their traditional nest sites, but not nesting yet. Do some loons actually delay nesting because of these biting insects? Other pairs seem to be doing just fine, and hopefully have nested in an area with fewer blackflies.

Loon Language

Perhaps one of the most fascinating things about loons is their haunting and variable voice. Loons are most vocal from mid-May through June. They have four distinct calls which they use to communicate with their families and other loons.

The Mournful “Wail” – An “ooohh ahhhh” is often the sounds of loons identifying or calling to each other; it can also signal initial signs of a mild disturbance.

The Laughing “Tremolo” – A trill or series of trills can be a sign of distress or alarm, and occasionally excitement.

The Crazy and Wild “Yodel” – This is the male territorial call, usually directed at unwelcome loons. Every male has a distinct yodel and transmits much information through the yodel – from how big the male is to his motivation to defend.

Hoots and Coos – On a quiet evening you can hear the loon family or group of loons in a “social gathering” communicating to each other.

Listen for loons and be sure to report your sightings to Vermont eBird, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life, and help us track their populations.

A GEM, A TEASE, AND A TRAP

Showy Lady’s-slipper (Cypripedium reginae) after a rainstorm in Eshqua Bog, Hartland, Vermont. / © K.P. McFarland – www.kpmcfarland.com

There are about 47 species in the orchid genus Cypripedium, the Lady’s Slipper. Lucky for me three of them bloom within just a short distance from my house. Yellow and Showy Lady’s Slippers grow in a nearby fen and the more upland, acidic loving Pink Lady’s Slipper can be found in mixed pine woodlands.

Gems of the forest to me, but just a tease and a trap for pollinators. There is no edible reward for their pollinating help. The beautiful pigmentation and scent entices insects to enter the flowers down through the labellum, the irregularly shaped petal that forms the “slipper”, of the Showy and Yellow Lady’s Slippers. Unlike most Cypripedium, insects enter the Pink Lady’s Slipper through a slit that runs the length of the labellum. Either way the insects become trapped in the slipper without any nectar and soon begin to move around wildly trying to find an escape route.

Pollen grains are stuck on structures called pollinia. These are behind a shield near the opening called the staminode. When the insect enters the flower, it cannot come into contact with the flower’s own pollen. This prevents self-pollination. To escape, the insect exerts pressure on the stigma creating a larger escape hatch. If it has pollen grains on its body from a previous flower, they are likely to stick to the stigma. The only passage to freedom from there is past the pollinia where a sticky mass of pollen will adhere to its body on the way out. With luck, it will visit another Lady’s Slipper to transfer the pollen. But after a few visits to these flowers, they usually catch on that there is no nectar reward inside the flower and begin to avoid Lady’s Slipper flowers. This might explain the low seed set for these orchids.

Who are the pollinators for these deceptive flowers? A study of the population of Showy Lady’s Slippers near my house found that over 90% of the pollination was done by hoverflies with a minor contribution from flower beetles. Others have found leafcutter bees visiting the flowers.

Recently, Martha Case and Zachary Bradford from the College of William and Mary came up with an ingenious method for discovering visiting pollinators. They used a piece of ribbon and a clip to block the escape passage from the slipper. They found a near threefold increase in pollinator detection in Yellow Lady’s Slippers. Ten bee species from four families (Andrenidae, Apidae, Halictidae and Megachilidae) were found in the flowers (read more about the study).

For an insect, beauty is indeed only skin deep when it comes to the Lady’s Slippers.

Self-medicating Bumble Bees

A bumble bee collecting nectar containing iridoid glycoside secondary metabolites from a turtlehead (Chelone glabra) flower. / © K.P. McFarland

Many plants rely on flower visits by pollinators such as bees in order to reproduce. When bees consume nectar and pollen, they must cope with naturally occurring secondary chemicals produced by plants, substances usually associated with plants’ defense against herbivores.

Why would plants expose their pollinators to these chemicals? How do they affect bee health? And what are the consequences of plant chemistry for pollination of wild and cultivated plants?

Leif Richardson, a VCE research associate, and his colleagues found that toxic chemicals in nectar reduced infection levels of the Common Eastern Bumble Bee parasite by as much as 81 percent by seven days after infection. In a press release, UMass Amherst evolutionary ecologist Lynn Adler says, “We found that eating some of these compounds reduced pathogen load in the bumblebee’s gut, which not only may help the individual bees, but likely reduced the pathogen Crithidia spore load in their feces, which in turn should lead to a lower likelihood of transmitting the disease to other bees.”

Read the published study and watch Richardson’s presentation at VCE’s Suds & Science series about his research exploring effects of plant chemicals on bumble bee – parasite interactions and bee foraging behavior. He also addresses the importance of wild bees to agriculture and ongoing efforts to halt their decline.

Finding Ferns

Last June, on an iNaturalist Vermont walk with interns and citizen naturalists, VCE’s Kent McFarland and Park ecologist, Kyle Jones, took a two-hour fern tour of Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park. Led by the group was able to find 22 species of true ferns and document 17 of those with photos in iNaturalist Vermont, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life.

Naturalist examines Goldie’s Wood Fern closely. © K.P. McFarland

There are 36 species of true ferns known in the Park, out of the 65 species found in Vermont. Finding nearly two-thirds of the species in the Park in just a few hours was a lot of fun and incredibly helpful for comparing the identifications of each species. There are nearly 3,700 fern observations in iNaturalist Vermont representing 54 species in iNaturalist Vermont now.

Ferns and their allies are seedless vascular plants. So how do they reproduce? Their life cycle has two different stages; the sporophyte (most of the mature plants you normally see), which release spores, and gametophyte, which releases gametes. The spores grow into tiny gametophytes with both male and female organs that release and capture sperm. A fertilized egg develops into a new sporophyte. It’s a very strange system. Check out this graphic that really helps to show how it all works.

Perhaps Vermont’s most famous fern is the Green Mountain Maidenhair fern, which was formerly described in 1991. It is only known from about 7 places in northern Vermont and adjacent Quebec in rare serpentine soils, and has yet to be reported to iNaturalist Vermont.

You can find a key to the ferns and their allies at GoBotany and learn more about each species. From rare to common, there’s plenty to find and learn about Vermont’s ferns. Explore, find, photograph, and share your observations with iNaturalist Vermont.

hi there, love your field guides. they are hard to read on my phone because the text is so small though, smaller than any other email i get.

food for thought.

thanks!

Thanks for the feedback. I checked and I see what you mean. That is terribly small. I will see if we can change the programming. Meanwhile, if you click on the title of any blog post in an email from us, it will take you to the web view, which is quite readable on my phone. Thanks again and thanks for the nice words about our posts! Best, Kent

Nice article.

The articles and photos on Loons is very well done and fantastic recordings of Loon calls. I learned a lot and thank you all.