Dawn light through the cliff net © Anna Peel

I open my car door and step out into the sun of a new day on Mount Mansfield. There’s an urgent to-do list of tasks awaiting me, with a team to coordinate and nets to set up, but there’s something I need to do first. I breathe in.

My lungs have been downland all week, full of the smells of a dirty car in summer, sweat and sunscreen in the garden, chicken poop on the porch steps, all the rich human and domestic odors that bloom in the heat of June. Mansfield air is something else entirely. A deep breath of the mountain is medicine that reaches right inside you, all mineral and green. It’s full of the kind of indifferent, magnificent wildness that challenges humanity to bend to its power, rather than the other way around.

Summer dawn on Mansfield, when the wind is warm and sweet and the sun is just beginning to cast strawberry shadows against the net, is another essential moment of peace for me in the busy week. Each morning this year, there’s one birdsong in particular that I’m waiting for as the dawn chorus swells around me: the crescendo-decrescendo trill of a male Blackpoll Warbler asserting his territory.

When a male Blackpoll first arrives on the mountain in late May, he is immediately in competition with other males to corner the best territory and find a mate. Once he has secured a patch of mountain and a mate, he then has to prevent other males from encroaching upon either. As a result, a researcher armed with a speaker and a recording of a Blackpoll song in May or June is almost guaranteed to provoke nearby males into responding to that recording. This allows us to quickly and efficiently target and capture birds for tag deployment, without spending very long in their territory.

However, once fledglings emerge from the nest in July, Blackpolls no longer have any pressing reason to defend a particular territory. This results in a sharp drop in their responsiveness to the song of an unfamiliar male, as well as any interest in our speakers.

In last year’s pilot season of a new collaboration between VCE and National Audubon, with funding by Massachusetts Clean Energy Center (MassCEC), we fitted Blackpolls with harnesses containing tiny archival geolocators with the ability to track their location, speed, and elevation as they made their perilous, days-long transatlantic journey to their non-breeding territories in South America and back again. The goal is to ascertain whether they are flying at a height that could bring them into contact with offshore windmills.

In 2024, we deployed fifteen tags on Blackpoll Warblers throughout the breeding season, which required us to come up with inventive ways to coax the incurious July and August Blackpolls into our nets. This summer, we deployed all twenty Blackpoll tags before the end of June, in an intense and satisfyingly efficient joint effort.

Each of the Blackpoll Warblers equipped with a geolocator harness also gets a unique combination of colored legbands to help us identify the bird from afar. As you can see in the photo of a Blackpoll wearing a geolocator, the tag is relatively low-profile, with just a light-detecting stalk emerging from the feathers.

Colored legbands are much easier to spot than the tag itself. They give the bird an appearance of “fat legs” even with the unassisted human eye. With binoculars to see the unique colorband combination, we can identify individual Blackpolls before we even have them in the hand.

An adult male Blackpoll Warbler wearing one of our geolocators © Alicia Brunner

We haven’t yet recovered any of 2024’s geolocators, but the mountain is full of Blackpolls on the move. Every new visit carries with it the possibility that today will be the day we find one of last year’s tagged birds, carrying with it a wealth of precious information that could tell us whether or not these intrepid little birds have the potential to interact with offshore wind farms along their migration route.

High-Intensity Workouts for Birds

Since 2024, the VCE team has been collaborating with researcher Dr. Sarah Deckel to capture Swainson’s Thrushes and Bicknell’s Thrushes, and compare the two species’ energy use at high altitudes.

Swainson’s Thrush is an elevational generalist; Dr. Deckel has found them breeding at elevations as low as 800 meters on Mount Washington, and we regularly catch Swainson’s Thrush with breeding evidence at our Mansfield station, which sits at 1,173 meters.

Bicknell’s Thrush, on the other hand, are high-elevation specialists, well adapted to extreme mountain conditions. The lowest-elevation Bicknell’s Thrush nest found on Mansfield was at around 950 meters, but the majority of breeding Bicknell’s Thrush on Mansfield are to be found above 1100 meters.

Dr. Sarah Deckel banding a target-netted Swainson’s Thrush on Mount Mansfield © Sarah Deckel

Dr. Deckel’s theory is that the generalist Swainson’s Thrush might be working harder than the specialist Bicknell’s Thrush to survive at Mansfield’s ridgeline, where temperature swings, wind gusts, and rainstorms can be far more dramatic and frequent than at lower elevations. She’s testing that theory by taking blood samples from both species to compare a new molecular technique using oxygen isotopes. Once she’s back in the lab at the end of the field season, she’ll run the samples to see which samples have higher concentrations of oxygen-17 and oxygen-18, oxygen isotopes that build up in the bloodstream during metabolic effort.

It’s been a real pleasure to collaborate with Sarah on Mansfield. By helping us with our long-term monitoring, she’s been able to catch more Swainson’s and Bicknell’s than she would have been able to on her own, and we’ve been able to open more nets for more extensive coverage of Mansfield’s breeding bird population!

Baby Birds Emerge

The month of July brought new species up to the ridgeline, as birds began to range away from their breeding territories, a phenomenon known as “post-breeding dispersal.” In addition to these restless adults, fledglings emerged from their nests all over the mountain, shepherded by their anxious parents. We’ve cooed over downy young Golden-Crowned Kinglets and admired the plumage of a male Bay-Breasted Warbler.

All summer long, we have been graced by the glorious cascading song of a Winter Wren singing just below the Nose of the mountain; in the past few weeks, we were lucky enough to catch a handful of this wren’s fledglings. There’s no size difference between a fledgling wren and an adult wren—both weigh barely more than two pennies put together, and both can put on a real show of ferocity, either tangling in the net or wriggling in the hand. The best way to tell the difference is by examining the patterns in their wing: the barring in fledgling wingfeathers lines up across the wing, creating relatively uniform stripes. This is because they grow every wingfeather at the same time. Adults, on the other hand, replace their wingfeathers sequentially, meaning that the barring on their wingfeathers does not align into neat stripes.

The neatly-striped wingfeathers of a fledgling Winter Wren © Mike Sargent

The ruby-red eye of an adult female Sharp-Shinned Hawk © Anna Peel

We also had the opportunity to see a Sharp-Shinned Hawk up close not once, not twice, but three times! Our first Sharp-Shinned Hawk of the 2025 season was an older female, caught in our nets on our very first visit to the mountain in May. Her plumage and rich red pupil told us she was at least two years old. The last glimpse we had of her was of her acrobatically winging out of our hands and away over the ridgeline. The next Sharp-Shinned Hawk we caught was younger—what we call a “second-year male”—and a little less savvy. We first caught him in the second week of July, and then found him in our nets again the next week!

What a Difference a Year Makes

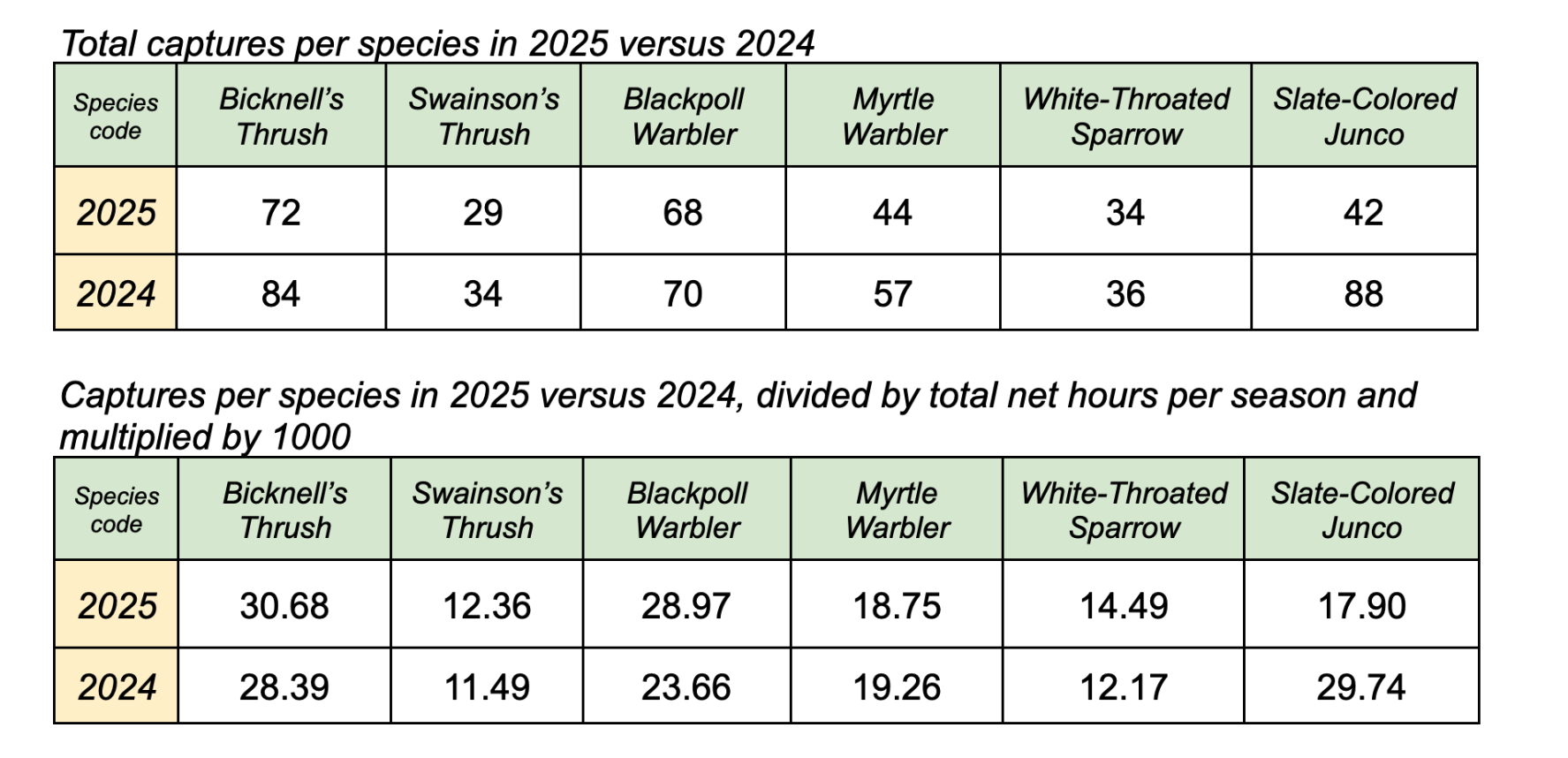

Taking a moment to compare our capture numbers from last year with this year, one thing leaps out at me. Our Slate-Colored Junco capture numbers are half of what they were last year, although all of our other target species are visiting our nets at roughly the same or higher rates as 2024. This trend remains even when capture numbers are adjusted to reflect the total number of active net-hours of banding each season.

Dark-Eyed Juncos are one of North America’s swiftest-declining bird species, despite their wintertime abundance in New England backyards. According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, their numbers nationwide have dropped by 42% since the late 1960s; our mountaintop trend only reinforces the necessity of keeping watch over even these seemingly common species.

In terms of species diversity, in 2024 we caught birds from 36 species, whereas in 2025 only 29 different species graced our nets. We also haven’t been subject to the remarkable deluge of hatch-year Pine Siskins that besieged Mansfield in 2024, which was an irruption year for the species—in fact, we haven’t caught a single one in 2025 so far, although on our second July visit to Mansfield, six chatty Siskins were hopping busily back and forth across the access road each time we checked our Lake View nets.

We’ll be back on the mountain in September to look for Bicknell’s Thrush as they begin their migratory journey to the Caribbean. We might also get the opportunity to see our Blackpoll Warblers equipped for their long southward flight, beautifully chubby once they’ve doubled their body weight with fat.

There’s no season like fall migration for encountering high species diversity, and I for one can’t wait to see what September will bring us.