By Kent McFarland and Bryan Pfeiffer

Here in Vermont, we dream of June during the darkest days of January. Verdant wooded hillsides glowing brightly under a robin egg sky. Warm afternoon breezes rolling through the valleys as we lounge by the clear waters of a cold river. The chorus of birds waking us each morning. The smell of freshly cut grass wafting through the window. We forget about the clouds of black flies, the hum of the mosquitos and the rainy days. June is a dream here. Its days last forever.

Cowbirds Being Cowbirds

Even devoted birdwatchers find it tough to love the Brown-headed Cowbird. Black body. Fat head. Grating voice. And the female is a homely gray. Not exactly a glamor couple. But appearance is only part of the cowbird’s PR problem.

What most disturbs some birders is cowbird breeding behavior, which biologists call “brood parasitism.” Cowbirds build no nests of their own. After having indiscriminate sex, females wander the landscape laying eggs in the nests of other songbirds, leaving the unwitting foster parents to raise the cowbird chicks.

This doesn’t always turn out so well for the host family. Cowbird chicks exercise brutal sibling rivalry. They tend to grow faster and larger than their adoptive siblings, gaining an edge in gobbling the food delivered by parents. During the melee at feeding time, cowbird chicks might stomp on and smother nestmates. They sometimes even push eggs or chicks out of the nest.

The most poignant evidence of all this comes after the cowbird fledges. Birders occasionally encounter an elegant songbird – a northern cardinal, a chipping sparrow, or a yellow warbler, for example – feeding a hulking cowbird chick out of the nest (see photo). It’s like a human mom with triplets feeding a fourth who happens to be an NFL linebacker.

But let’s give cowbirds their due. After all, cowbirds are simply being cowbirds. Like the rest of us they’ve adapted to changes in the landscape. Read more in an essay from VCE Research Associate Bryan Pfeiffer published in Northern Woodlands magazine.

Black Flies Aren’t Just annoying to us

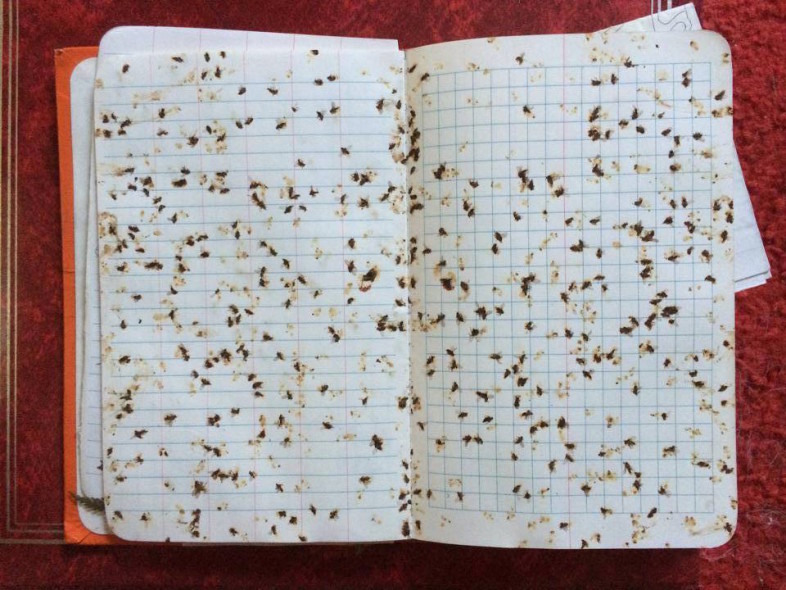

Noel Dodge was one of our best student interns on the Bicknell’s thrush project. He’s now a professional biologist and still working hard on conservation issues and still comes up to Mt. Mansfield from time to time to help us band birds. One day while banding Bicknell’s Thrushes on Stratton Mountain, he decided to collect a sample of blackflies around us. His method? Field notebook slaps. Here’s a few hours of work on June 16, 2002. Field work can be tough! Imagine our necks and ears after that morning!

The Northeast is home to over 40 species of blackflies. But only 4 or 5 are considered to be really annoying to humans. In some cases, blackflies may not bite but merely annoy us, as they swarm about our head or body (Hint – they like dark objects. Choose clothing wisely). Only the females bite and fortunately, for us, most species feed on birds or other animals.

Biologists have found Peregrine Falcon chicks being killed by recent outbreaks of blackfly swarms in the Arctic, possibly due to climate change. Farther south in Wyoming, researchers found blackflies killed 14% of the Red-tailed Hawk nestlings that they monitored, and they were the only known cause of mortality. In 1984, heavy spring rains in the upper Midwest apparently caused ideal breeding habitat for blackflies, whose populations exploded. Dense clouds of them attacked nesting Purple Martins causing widespread die-offs and colony-site abandonments. Blackflies can be a big problem for many nesting birds.

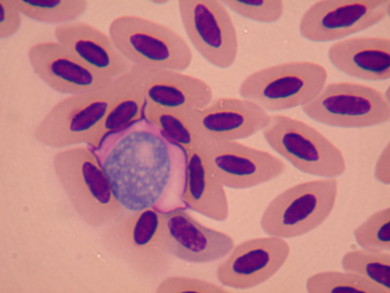

A stained blood smear showing Leucocytozoon (large purple blob) in Bicknell’s Thrush blood (cells are small dark purple). / © VCE

But they just don’t bite birds, they also transmit disease. Leucocytozoon is a genus of parasitic protozoa. They use Simulium blackfly species as their definitive host and birds as their intermediate host. There are over 100 species and more than 100 species of birds have been recorded as hosts.

Recently, VCE teamed up with Vermont-based biologist Ellen Martinsen and found that in Vermont’s Green Mountains, 67% of females were infected by Leucocytozoon sp. and 23 males, 48% were infected by Leucocytozoon. Our colleagues in New Brunswick, Canada found that 69% of the Bicknell’s Thrushes they sampled were parasitized by Leucocytozoon.

Blackflies breed exclusively in running water. Some species live in large, fast-flowing streams, others in small, sluggish rivulets. Almost any kind of permanent or semi-permanent stream is occupied by some species. Large blackfly populations indicate clean, healthy streams since most species will not tolerate pollution.

Blackfly females lay their eggs on vegetation in streams or scattered over the water surface. The eggs hatch in water and larvae attach to submerged substrate. They feed by filtering water for tiny bits of organic matter. Once the larvae are mature, they pupate underwater. Emerging adults ride bubbles of air, like a hot air balloon, to the surface and fly away. They mate nearby and females search for a blood meal before laying eggs.

Avian Infidelities

Blackbirds do it. Chickadees do it. Even educated emus do it.

Some birds are cheaters. Their trysts, dalliances, one-morning stands, and other infidelities would constitute a racy script for a wildlife soap opera.

But first, the faithful: In the vast majority of bird species, one male and one female unite for the purpose of raising young. In this classic form of monogamy, or “single marriage,” the pair stays together either for a single breeding season (the case among most songbirds) or for as long as they both shall live (in geese, gulls and swans, for example).

Among the rest (or the restless, as the case may be), polygamy, or “many marriages,” ranges from casual to calculating. Read more in a blog post from VCE Research Associate Bryan Pfeiffer.

How To Catch a Dragonfly AND TELL US ABOUT IT

Vermont has 142 species of dragonflies and damselflies, and catching one in a net is a lot more challenging than it might appear. So we’ll turn to an “encore edition” of Vermont Public Radio’s “Summer School” series. In one episode, VCE Research Associate Bryan Pfeiffer offered a lesson on swinging for dragonflies in the big leagues.

The atlas of dragonflies and damselflies of Vermont has been updated at Odonata Central by the Vermont Atlas of Life. Two new discoveries in 2014 now brings the total number of Odonata, the order of insects containing dragonflies and damselflies, to 142 species.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of odonate experts Mike Blust and Bryan Pfeiffer, the atlas covers the distribution of all 142 species known from Vermont, including all of the resident and regular migrant species, as well as all known vagrants – individual insects appearing well outside their normal range. Blust and Pfeiffer conducted fieldwork across Vermont for years, with the help of other enthusiasts, and compiled an amazing dataset of Vermont’s odonates. Their work will soon be published in Dragonfly Society of the Americas journal Bulletin of Odonatology.

Since 2013, biologists and citizen naturalists with the Vermont Atlas of Life have contributed new records to the effort through iNaturalist Vermont and directly to Odonata Central. And there have been some remarkable finding over the last few seasons. Read all about them on our blog.

You can help us record and map all the dragonflies and damselflies in Vermont, rare or common. This year, join a field trip and learn, take digital photographs and submit your observations to Odonata Central or to iNaturalist Vermont, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life. There is much to discover about biodiversity in our own backyards.