By Bryan Pfeiffer and Kent McFarland

“Stick Season,” as we call it here in New England, when the woods are gray and cold, has been anything but lifeless this November. Fall migration continues with passing shorebirds, waterfowl and the final hawks drifting south. The year’s last butterflies — sulphurs and late Monarchs — remain on the wing. And winter visitors, including Snow Buntings, seem to be arriving in good numbers. We’re also expecting a wave of Common Redpolls. Here’s more in your Field Guide to November.

A Rush of Redpolls

The Tadoussac Bird Observatory, on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River about 200 kilometers downstream from Quebec City, documented an amazing flight of 14,391 Common Redpolls in a mere seven hours on October 24. Although the birds seem to be remaining north of the St. Lawrence, we may have redpolls in our future here in the Northeast this winter. Watch for them with this live map from Vermont eBird.

The Snows of November

Although a quick look at eBird data doesn’t suggest a snowstorm of Snow Buntings, lots of birders are finding them this month. VCE Research Associate Bryan Pfeiffer reports nearly stepping on a flock at Dyer Point on the Maine coast last weekend. Here in Vermont, birders from Mt. Mansfield to the Champlain Valley have been reporting Snow Bunting encounters since late October. Away from Champlain Lowlands (which is traditionally the best bunting winter habitat here in Vermont), watch for flocks stopping in at windswept farm fields (where they find meals of grass seeds) or at your bird feeders. Meanwhile, Snowy Owls seem to be moving south in decent numbers this fall — but more so in the Midwest (particularly Wisconsin) than here in the Northeast. Our best evidence for that is (of course) eBird. Here’s the latest on the Snowy Owl movements this winter.

And the Butterflies Flew No More

Clouded Sulphur (Colias philodice) takes a break in the high peaks of the Presidential Range, NH. / © K.P. McFarland

November may be known for its gray skies and brown landscapes here in the Northeast, but there are always a few glorious blue days with temperatures rising into the short-sleeve zone. And with those days come the last of the fluttering butterflies. You can find a few Clouded and Orange Sulphurs dancing about the fields, or late Monarch attempting to wing its way southward. Maybe you’ll run into a camouflaged anglewing — Question Marks and Eastern Commas — adding punctuation to your fine day outdoors. And the truth is, during many Novembers, you might now have a better chance finding them. On average, butterfly flight periods are likely lengthening.

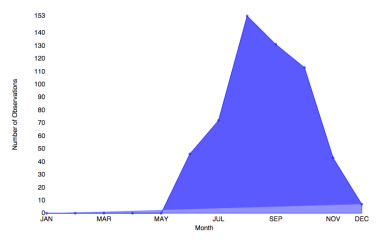

Clouded Sulphur flight season in Vermont from e-Butterfly.org data. Some are found in the Champlain Valley as late as early December.

A recent study in Canada showed that the timing of butterfly flight seasons responded to temperature both across the landscape (variation in average temperature from site to site in Canada) and across time (variation from year to year within each individual site). They found that given the widespread temperature sensitivity of flight season timing, with increased warming we can expect long-term temporal shifts of 2.4 days for every 1.8 degree F change in air temperature for many if not most butterfly species.

Help us document the late season fliers. When you find a November butterfly, snap a photograph and submit it to e-Butterfly.org, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life. Let’s see who can find the latest butterfly in 2015!

A Wingless Winter Moth

By now virtually all our moths and butterflies are overwintering as either eggs, caterpillars, or pupae (a cocoon in the case of a moth). But as you walk through deciduous woods in November and even into December, look for an exception – a lesson in adaptation, fertility, and feminine sacrifice going by the name Bruce Spanworm. These moths are also called Hunter’s Moths because they fly in the company of deer hunters.

As a caterpillar, Bruce Spanworm (Operophtera bruceata) is one of the inchworms, a member of the large moth family called Geometridae (which means “earth-measuring”). As an adult, Bruce Spanworm is not particularly showy. Its forewings, about 1.5 inches across, are dull gray with dark flecking, and its hindwings are even less dramatic. But who needs pizzazz when you’ve got the audacity to fly around in winter? Kent explains how it happens on his blog and Bryan also offers a perspective on his blog.

The Last Dragonfly

We don’t call it Autumn Meadowhawk for nothing. Find it this autumn in your local meadow hawking for insects. One of about 140 dragonfly and damselfly species in Vermont, this one begins its flight season in July. Our latest flight date on record is November 26. Vermont has five of these red meadowhawk species (in the genus Sympetrum), only one of which, this one, has yellow legs and most likely the last adult dragonfly you’ll see until April (unless you head south this winter). Look for it drifting past fall hawkwatch sites or baking what little sun and warmth is available in various open habitats late in the year. Submit your sightings to iNaturalist Vermont.

We don’t call it Autumn Meadowhawk for nothing. Find it this autumn in your local meadow hawking for insects. One of about 140 dragonfly and damselfly species in Vermont, this one begins its flight season in July. Our latest flight date on record is November 26. Vermont has five of these red meadowhawk species (in the genus Sympetrum), only one of which, this one, has yellow legs and most likely the last adult dragonfly you’ll see until April (unless you head south this winter). Look for it drifting past fall hawkwatch sites or baking what little sun and warmth is available in various open habitats late in the year. Submit your sightings to iNaturalist Vermont.

The Butcher Bird Arrives

No, not the turkey on your platter. We’re talking about Northern Shrikes, aka “butcher bird” – a predatory songbird that breeds in the far north and winters in southern Canada and the northern United States. Shrikes feed on small birds, mammals, and insects, and are known for impaling them on spines trees or barbed wire fences. VCE’s Chris Rimmer discovered that they can return winter after winter to the same territory. Using band recoveries, he found 12 cases in which shrikes were recaptured at or near the same winter location one to three years later. Keep a look out for these feisty songbirds and be sure to report your sightings to eBird.

“Blue Fuzzy-Butts”

Those tiny tufts of powder-blue lint floating, well, like floaters in your field of view, aren’t outcasts from the dryer cycle. They’re hearty November insects, the adult form of a wooly aphid species. We more often see these aphids gathered in a mass on speckled alder, sucking liquids and covered with a waxy white coating resembling cotton or wool (like the image here). But the adult stage (the blue-lint form) is now on the wing. Bryan’s partner Ruth calls them “Blue Fuzzy-Butts.” Bryan reports on his blog.

Wonderful article with great photos!

Do we get snow buntings in Woodstock? Great article. Project feeder watch with Cornell university begins this Saturday , will keep my eyes open all these winter birds…already have had a bunch of purple finches

We do sometimes. Check around Billings Farm (have seen them along parking lot and pasture there) and also over in fields in East Woodstock floodplain below the sewer plant. Here’s a link to Vermont eBird map for sightings over the last decade in Woodstock: http://ebird.org/ebird/vt/map/snobun?neg=true&env.minX=-72.73912978950193&env.minY=43.52740425204128&env.maxX=-72.25126815620115&env.maxY=43.681043386375116&zh=true&gp=false&ev=Z&mr=1-12&bmo=1&emo=12&yr=last10. Good luck finding them!

I appreciated the above information. Your photos are beautiful.