Monarch nectaring on Joe-pye Weed during migration. / © K.P. McFarland

It can happen almost anywhere. On a cool, foggy morning, for example, when fall warblers drop from their nocturnal migratory flights into your backyard. Or along a big river some evening when you notice a Common Nighthawk moving south — then another, and another. Or on some summit when the Broad-winged Hawks kettling above and Monarchs gliding southward convince you that summer is indeed over. Here is your field guide to life on the move in September.

Hawkwatching Confidential

If it’s September, it’s a broadwing up in the sky. Okay, that’s a generalization, but not a bad one. So if those migrating hawks appear to you to be little more than specks in the sky, or if you need to brush up on your hawkwatching skills, VCE research associate Bryan Pfeiffer offers some advice on his blog. And if you ever wanted to know what it was like to go on a hawkwatch, join Outdoor Radio on the expedition to the Putney Mountain hawk watch.

Monarch Migration – Shaping up to be a Big Year in the Northeast

Judging by the observations from around the Northeast, this summer has been a productive year for Monarch butterflies, and it could be one of the best fall migrations here since 2007. When the hawks are moving, the Monarchs are too. Both ride the air currents southward. The Monarchs barely flap a wing. On days with unfavorable winds, you can often find them fueling on flower nectar, especially in large fields of Red Clover. By the time cold air settles into the Northeast, the Monarchs are well on their way to Mexico.

Each winter in small area in the transvolcanic mountains not far from Mexico City the entire population of Monarch butterflies from east of the Rocky Mountains wait in the trees. These are small peaks ranging from 7,800 to 11,800 feet in elevation and covered with Oyamel Fir trees (Abies religiosa), a species closely related to the Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea) found on the mountain tops here in northeastern North America. In 1984, a study found that there may have been as many as 60 overwintering sites that can be used by the butterflies, but now there are just a few each winter. A site may contain up to 4 or 5 million monarchs per acre and cover as little as one-tenth up to 8 acres of fir forest.The butterflies arrive from the north in November to late December and hang out on the trees metabolizing fat reserves that they have built up during migration. Remarkably, they actually gain weight on migration and arrive on the wintering grounds with fat reserves for the winter, unlike songbirds, which require huge fat stores to burn on migration.

The winter generation lives up to 8 months while the successive spring and summer generations are lucky to live 5 weeks. It takes up to 6 generations of spring and summer Monarchs to produce the final “super-Monarch” that migrates to Mexico in autumn and then back to the southern United States in spring.

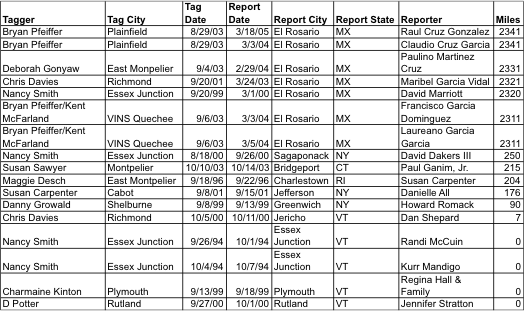

How do we know that at least some Monarchs from the Northeast actually make it to Mexico? Tracing unique chemistry in their wings tells us that about 15% of the overwintering population comes from the Northeast on average. And, we also know directly from Monarch tags. Many of us have been tagging adults during fall migration in cooperation with Monarch Watch. Using small tags like tiny bumper stickers with unique identification numbers on them, volunteers capture and place them on a Monarch’s wing in the fall. With millions of Monarchs, the odds of a recapture are very poor. Here in Vermont we have had a few lucky finds. There have been 7 Monarchs tagged in Vermont and found in Mexico! Maybe you could be a lucky tagger. Anyone can do it. Just visit Monarch Watch for more details.

You can also watch Monarchs virtually move southward on the internet as people like you report sightings to Journey North, e-Butterfly.org, and iNaturalist. Whether you find eggs or caterpillars, see them nectaring or actively migration southward, you can add your sightings to help get a picture of this amazing migration across the continent.

Humming Along

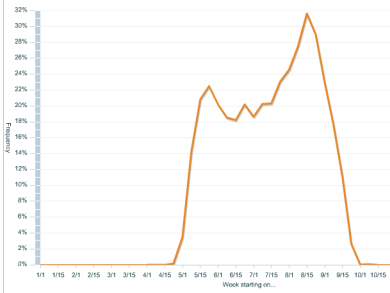

Frequency of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds reported on Vermont eBird checklists.

When the flowers stop blooming and insects stop flying, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have gone south. Some adult males start migrating south as early as mid-July, but the peak of southward migration is August and early September, and by October they’re all gone.

Most, if not all, of the hummingbirds at your feeders in September are migrants and not the same individuals you’ve watched all summer. Since they all look alike, it’s difficult to know for sure, but banding studies have shown the turnover. It’s not necessary to take down feeders to force hummingbirds to leave, and in the fall all the birds at your feeder are already migrating anyway. Keep them up as long as you can and just maybe a wayward rare species will find them.

Where do they all go? There is some evidence that more of them travel around the Gulf of Mexico in fall migration, rather than cross it as they do in spring. They’ll spend the winter in Mexico and Central America. Weighing a mere two-tenths of an ounce, they’ll make the round trip back in April and delight us once again with their bright colors and active flights after our long white winter.

Make sure you add your sightings to Vermont eBird and help track their phenology.

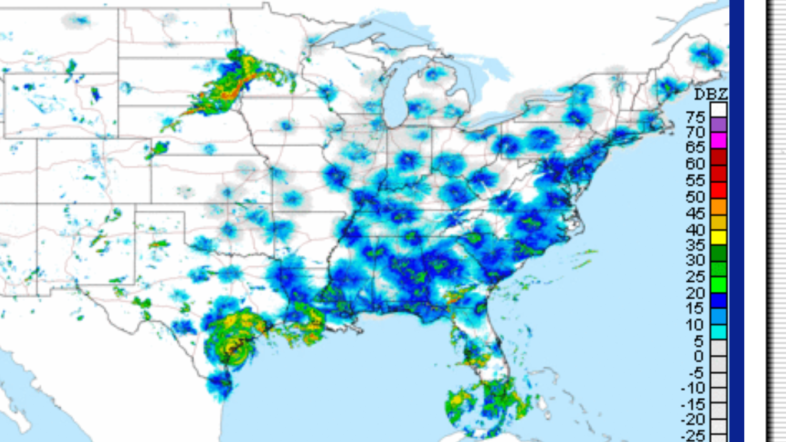

Ghosts on the Screen

When radar was first deployed, operators called them “ghosts”, mysterious echoes seen on radar screens on clear nights. Some of these were caused by migrating birds and insects. Since the first units were placed along the Gulf Coast in the 1950s, ornithologists and birders have become increasingly aware of the power of using radar as a tool for understanding bird migration. In addition to detecting and depicting meteorological phenomena, this radar network can be used to watch and to track the movements of birds. And, its available at your fingertips. When a cold front passes through and the winds are from the northwest, visit the NOAA weather radar site on the internet when it becomes dark outside and see if the birds have lifted off and are headed southward. Learn more about radar ornithology from the eBird blog.

Green Darners on the Move

A mere three inches long and weighing just four-hundredths of an ounce, it’s gliding on four wings thousands of feet in the air. With hundreds, maybe even thousands, of other individuals and little fanfare, it left a small Vermont pond and struck southward. Autumn is a season of migration and this Common Green Darner dragonfly is headed to warmer waters thousands of miles away, perhaps as far as Central America or the Caribbean.

Dragonfly migrations have been observed on every continent except Antarctica, with some species performing spectacular long-distance mass flights. A dragonfly called the wandering glider is the long-distance champion, making flights across the Indian Ocean that cover twice the distance of monarch butterfly migrations. In North America, dragonfly migrations occur annually in late summer and early fall, when millions of insects, hatched in the north, move southward. Of North America’s over 330 dragonfly species, only nine regularly migrate.

North America’s most abundant and widespread migrant dragonfly is the Common Green Darner. In the spring, just after the ice has disappeared from the ponds, green darners suddenly appear, well before any local dragonflies have emerged. These are migrants from the south, having flown from perhaps Florida, the Caribbean, or Mexico. They breed soon after arriving, and their nymphs develop quickly in water warmed by the spring and summer sun. Many adults emerge from the ponds in August. They feast on insects to pack on fat, perhaps increasing their weight by up to a third. But instead of breeding at their natal site, they begin a southward migration that may span a month or even longer.

Migrating only during daylight hours, green darners can fly more than 60 miles a day with favorable tailwinds from the north. When the winds turn against them, they stop, sometimes for several days, to dine on mosquitoes, gnats, flies and other insects until the north winds urge them onward. But no one knows where they are going exactly…but VCE biologists are working to solve the mystery.

Hi Kent,

Terrific overview of what to expect in September. Here on the Lake Michigan shore we too have seen the reemergence of the Monarch after several years of very small numbers. We have also seen more abundant growths of the milkweed, which here seem to be a favorite for the Monarch. I’m going to pass this along to some of my Michigan friends and family. Good stuff.

Kathy and I are headed back to NH in a couple weeks. It’s hard to leave this spectacular coastline but we look forward to fall in the Conn River Valley.

Good to hear they are doing well out there too. I have heard this from several others too. Would be nice to see a little population jump in the winter grounds this winter for them. Safe travels!