A Serendipitous Orchard Oriole Extravaganza

Orchard Orioles on their Latin American wintering grounds. From left: adult male (© Miguel Díaz), yearling male (© Karine Scott), female (© Carlos Alvarez N.).

Birders live for the unexpected. Nothing thrills us like an unforeseen avian find—a storm-tossed vagrant, a wayward spring overshoot, an out-of-season lingerer, or an astounding concentration. It’s all about discovery, surprise, serendipity. And, birds, owing to their supreme mobility, are more likely to astonish us humans than just about any other animal group.

For me, Panama City provided a recent encounter that was both fortuitous and unforgettable. During my recent layover there, en route back to Vermont from a 3-week field trip in Cuba, I stumbled upon a winged torrent of Orchard Orioles. On February 8, during the hour before dusk, I ventured out from my hotel (the Crowne Point), a mere kilometer from Tocumen International Airport, to casually check a patch of semi-open vegetation I could see across the busy road. Crossing a pedestrian overpass at 5:10 pm (the road was that busy), I observed a loose flock of 20+ songbirds crossing the road below me, heading towards an extensive patch of very tall, cane-like grass (elephant grass, I believe). Many of the birds’ underparts showed a rusty cast, but, lacking a Panama field guide, I figured my fleeting glimpse would lead to an inconclusive ID.

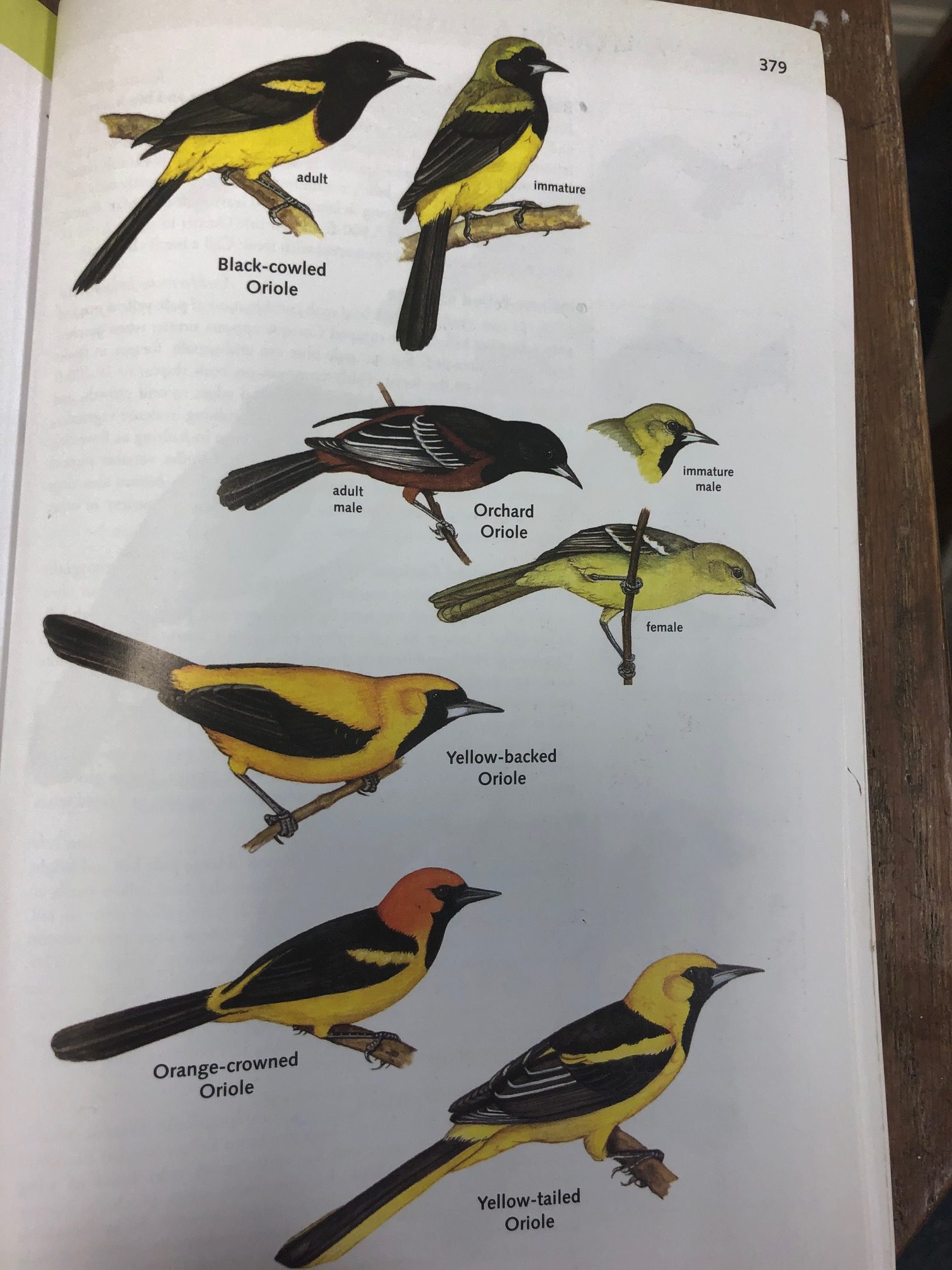

Five species of orioles found in Panama: 4 year-round residents and the North American migrant Orchard Oriole (second from top). © The Birds of Panama: a Field Guide (Angehr and Dean, 2010)

Three minutes later, I stood on a tree-lined dirt road just 50 m from whizzing vehicles, surrounded by familiar chattering calls and snatches of song. Hoisting binoculars, I realized the treetops above me were awash in orioles—Orchard Orioles. I immediately started counting. Small, noisy groups of 3-10 birds continuously streamed in from the southwest, “staging” briefly in the treetops, then leaving en masse (10-30+ birds) every 2-5 minutes. All moved northwest across the busy paved road. The majority of birds—perhaps 60%—were full adult males, followed by yearling males and females. Calling was near-constant, singing less frequent and not “full-throated” as during breeding. There was no question that this dusk flight led to a nocturnal roosting area, which had to have been the large stand of presumed elephant grass, or Napier grass, across the road. I continued to watch and count, mesmerized, as the flight continued at a strong pace until 5:40 pm, when it began to slow. Volume dropped dramatically from 5:50-6:00, and I saw fewer than 15 individuals between 6-6:10, after which I saw or heard none. My final tally: 665 birds, duly recorded in an eBird checklist! Given that I was positioned in one place the entire time and could not possibly have seen, let alone accurately counted, every bird that moved past, I’m convinced that this number is well below the actual number that passed by. And, the flight was well underway when I arrived. There could easily have been >1,000 birds. It may have been the most striking non-migratory movement of songbirds I’ve ever witnessed, in large part because it was so completely unexpected.

A small patch of elephant grass (well, probably…), Cenchrus purpureus, near the 2-hectare tract in which an enormous flock of Orchard Orioles appeared to roost overnight in Panama City, 8 February 2020.

Intrigue got the better of me overnight, and I was back before dawn the next morning, positioning myself in the same spot, hoping to intercept a return post-roost dispersal flight. It was still completely dark when I arrived at 6:00 am. I waited until 6:35, at which point full daylight had arrived, but saw and heard no orioles. I began walking and birding along a dirt road that parallels the busy main road, when at 6:40 I heard the unmistakable chattering of orioles and saw a group of 20 birds fly from the same treetops many had used the previous evening, then pass right overhead. I immediately began counting. An extraordinary spectacle unfolded over the next hour, with steady pulses of birds in groups of 5-30, most stopping briefly in nearby broadleaf trees before moving past me. The flight was heavy from 6:50 to 7:20, after which it slowed from 7:20-7:30, and further from 7:30-7:40. The last two individuals passed over at 7:43 am. I left the site at 7:46 and continued birding, at which point I found a single adult male foraging about 150 m away at 7:52 am.

As during the previous evening, birds were very vocal, but I heard relatively little singing, mostly calls. Height of birds passing overhead ranged from 2-50 meters, most 10-25 m above me. Again, the majority of orioles for which I could determine age and sex (~50%) were full adult males, the rest composed about equally of yearling males and females. All birds were flying in the exact opposite direction of the previous evening’s flight, when they approached from the southwest and moved northeast. The morning flight was universally oriented to the southwest. There is no doubt that I missed birds moving past. A few groups were 50+ m to the north and west of me, and I could easily have missed birds that were higher or further away. I counted (and eBirded) a staggering (to me, anyway) 1,235 birds, and I’d be very surprised if the entire flight didn’t include at least 1,500 individuals. And who knows how many others might have streamed in (and then back out) to and from other areas well beyond my view??

Nocturnal roosting in non-breeding songbirds is hardly a new phenomenon to science. Blackbirds and starlings are known to congregate in enormous flocks of up to several million birds in southern U.S. wetlands and swampy deciduous woods. Such congregations of North American migrant passerines are, however, less well-documented on their Neotropical wintering grounds.

Having recently read VCE Advisory Council member Roger Pasquier’s book Birds in Winter, I recalled a passage in which he mentioned winter communal nocturnal roosts of both Orchard and Baltimore Orioles in Panama. In fact, Roger recounted reports of 300-400 roosting Orchard Orioles near the Tocumen Airport from December of 1973 through January of 1974. So, it wasn’t as if I had made a startling new discovery! However, some digging on eBird revealed that the concentrations I observed exceed any others, by a longshot. Reviewing high December–February counts for each country within the known winter range of Orchard Oriole (all of Central American, Colombia, and Venezuela), I found only one count of 500 birds, in southern Mexico. Most other all-time winter high counts are in the 150–200 range. Go figure.

My casual, exploratory, no-expectations dusk walk revealed a spectacle the likes of which I’ve never witnessed before, and may never again—a serendipitous thrill forever etched in my memory bank.

Thank you for that amazing description and for sharing the experience.

It was fun to read about this remarkable event! Thanks for writing about it so eloquently and sharing it with us.

How extraordinary, Chris!

How fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time to witness this!

I was amazed the other day of the dopler radar movement of birds moving over the Florida Keys. Hoping we will see yellow rumped warblers again this spring. Had them 2 years ago, first and only time in the 40 years we have lived in this same place.

Chris,

Great to have seen this. So wonderful to get good bird news

Vicarious exhilaration for all of us, Chris, thanks to your vivid description.