Biologists and Bicknell’s Both Tote Backpacks on Mansfield

Team BITH at the bottom of Haselton Trail prior to our first-ever on-foot ascent to VCE’s ridgeline banding site on Mansfield, a hike made necessary by heavy rains that washed out the toll road. From left: Latrice Hodges, Madison Sayers, Kevin Tolan, CCR, Chris Hansen, Nathaniel Sharp, Ari Lattanzi, and Walnut. © Charles Gangas

Poetic justice? Divine retribution? What goes around comes around? Revenge of the BITH? Call it what you will, but after >25 years of affixing miniature “backpacks”—radio transmitters, light-level geolocators, and GPS tags—to Bicknell’s Thrush (BITH) on Mt. Mansfield, VCE finally got its comeuppance last week. After a June 27 microburst severely washed out the upper toll road, Vail Resorts had no choice but to ban all vehicular travel until repairs could be completed. Team VCE, never one to shrink from a challenge, and determined not to miss a week of our field season, gamely decided to access our ridgeline banding site on foot—a first in our 31 years of avian studies on the mountain.

Besides, didn’t we owe a show of solidarity to those intrepid BITH, who toted their backpacks 1,500+ km to the Greater Antilles, and back? Fair is fair. So it was that on July 6, a crew of 7 VCEers assembled at the base of the Haselton Trail, donned our backpacks, and began the 5.5-km trudge up to Mansfield’s ridgeline. Of course, our backpacks weighed far more than the 4% of body weight that a 1.1-gram GPS tag adds to a typical BITH. Well, we may have been lugging overnight gear, food, and banding supplies, but at least we were on a well-marked trail over a relatively short distance, versus migrating hundreds of kilometers under cover of darkness across unfamiliar and potentially treacherous terrain that includes open ocean.

The ascent up Haselton Trail was both grueling and historic for VCE. Kevin Tolan on the trail’s wooded lower portion (left) and grinding out a final push up the Nosedive ski trail, with Mansfield’s summit in the distance (right). © Nathaniel Sharp

We made it up the Haselton Trail without incident, though not without exertion (some of us moving far more quickly and nimbly than others), reaching the uppermost parking lot by 5:30 pm. We had to wonder if BITH feel as spent after a night’s migratory flight as we all (OK, I…) did. We fanned out as usual to set mist nets, opening 33 in our continuing effort to blanket the ridgeline and intercept as many GPS-tagged BITH as possible. After the heady successes of our early weeks, when we recovered 5 backpacks during two different banding sessions, we fully expected return rates to diminish. So, when female #2821-79107 appeared in a net on the Lakeview South Trail at 8:45 pm, still sporting GPS tag #50485 and weighing a healthy 26.5 g, Kevin and I enthusiastically exchanged high fives. However, with no laptop on hand (remember, we backpacked…) to check her tag’s data and view a preliminary track of movements, we had to hold ourselves in suspense for 24 hours. More on that below…

A quiet and cool evening unfolded, and we literally had the ridgeline to ourselves—not a vehicle to be seen, including our own. We finished banding the last of our 16 birds at 10 pm and were soon splayed out in sleeping bags on the gravel parking lot, under a waxing moon. Alarms jangled at 4 am, and we had all nets open well before sunrise. That allowed just enough time for 2 juvenile Northern Saw-whet Owls to entangle themselves, a week or two earlier than we normally catch the species, and providing a memorable first handheld encounter for our two summer interns, Latrice Hodges and Madison Sayers.

VCE summer interns Latrice Hodges and Madison Sayers with their first-ever handheld birds, a pair of juvenile Northern Saw-whet Owls: 7 July 2022. © Nathaniel Sharp

The rest of our morning featured steady, if unspectacular banding, with the biggest surprise being a juvenile and adult male Common Grackle in the same net—as far as we can tell a first for the ridgeline. Julie and Emily Filiberti joined us ~6 am after hoofing it up the Halfway House Trail, and we were grateful for both their company and their help with banding and data recording. They may be the first mother-daughter pair to ever be photographed with handheld BITH!

Emily and Julie Filiberti ready to release two banded Bicklnell’s Thrushes in the early morning light on Mansfield’s ridgeline, 7 July 2022. © Nathaniel Sharp

Our final tally of 77 mist net captures included:

Northern Saw-whet Owl — 2 juveniles

Yellow-bellied Flycatcher — 2 (1 new, 1 return from 2021)

Red-breasted Nuthatch — 1 free-flying juvenile

Bicknell’s Thrush — 20 (16 males, 4 females); 7 new, 3 returns (2018, 2020, 2021), 10 within-season recaptures

Swainson’s Thrush — 3 new males

Hermit Thrush — 1 female with regressing brood patch

American Robin — 3 males; 1 new, 1 return from 2017, 1 within-season recap

Purple Finch — 1 male

Dark-eyed Junco (Slate-colored) — 8 (1 male, 2 females, 5 free-flying juvs)

White-throated Sparrow — 8 (4 males, 3 females, 1 free-flying juv)

Common Grackle — 2 (adult male with free-flying juv); highly unusual (if not a first) on ridgeline

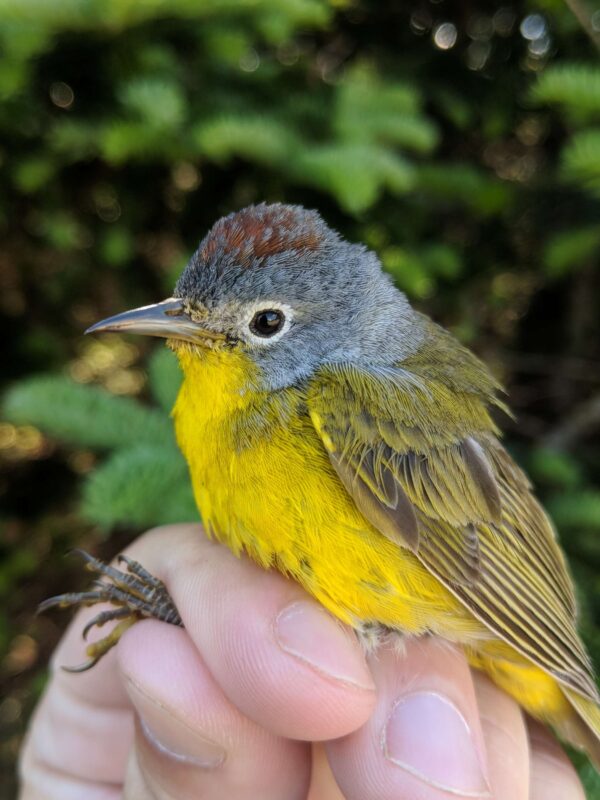

This dapper male Nashville Warbler was only the second of its species captured in VCE mist nets on Mansfield so far this season. © Nathaniel Sharp

Nashville Warbler — 1 male

Magnolia Warbler — 1 yearling male

Blackpoll Warbler — 10 (5 males, 5 females)

Black-throated Blue Warbler — 1 yearling male

Yellow-rumped Warbler (Myrtle) — 13 (8 males, 4 females, 1 free-flying juvenile)

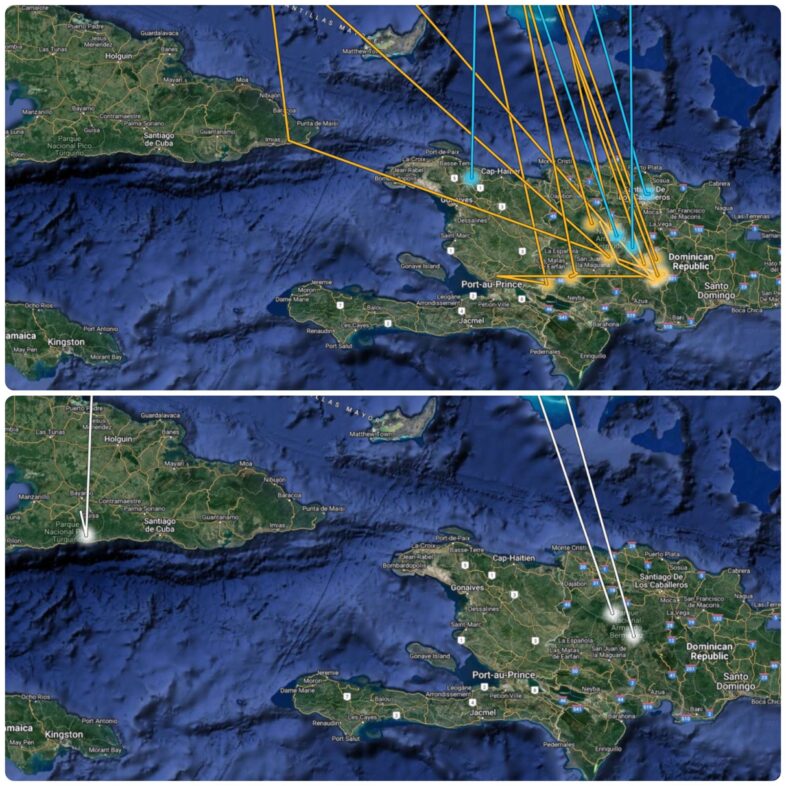

Back to BITH and their hemispheric movements, female #2821-79107—only our third recovered female of the 9 we tagged last year, and our 13th Mansfield bird overall (17 total, counting 4 males from Quebec)—turns out to have behaved like most of the other BITH so far. She overwintered in the Dominican Republic’s Cordillera Central, ~4 km east of the island’s (and Caribbean’s) highest peak, Pico Duarte (3,087 m asl). She was among the most sedentary of birds we’ve tracked, having settled on her winter territory by 1 November and still there when her GPS battery died on 3 May. She also claimed honors as the highest-altitude BITH we’ve ever documented on the planet; her winter territory of 6+ months occupied a patch of cloud forest between 2,460–2,665 m elevation!

Of the 17 BITH (14 males, 3 females) we’ve now tracked, 15 have overwintered in the DR, 1 in northern Haiti, and 1 (a female) in eastern Cuba’s Sierra Maestra. Of the 15 DR birds, only 2 males have settled outside of the Cordillera Central’s extensive mountainous terrain—1 in the degraded Sierra de Neiba near Haiti, 1 in Cordillera Septentrional near the north coast. Somewhat shockingly, we have yet to recover a single BITH that spent time in Sierra de Bahoruco, which supports Hispaniola’s second largest region of cloud forest, much of it still intact. We’re truly puzzled by this, especially in light of our band recovery of a male BITH that we banded on Mansfield in June of 1995 and mist netted a mere 6 months later at VCE’s Pueblo Viejo study site in Bahoruco. That bird provided the first-ever direct evidence of a VT-DR migratory connection.

Overwinter locations and late winter movements of GPS-tagged BITH: top shows males (orange = 10 Mansfield-tagged birds, blue = 4 tagged in Quebec), bottom shows females. Map courtesy of Kevin Tolan.

Until we dig more deeply into our GPS tag data, insights will remain limited, but the overall pattern so far indisputably confirms that overwintering BITH are highly concentrated in the DR. And, it appears that the mid-late winter intratropical migrations (ITMs) we suspected are not occurring. Only 4 birds (3 males and the Cuba female) have shown any notable movements from their discrete early winter territories, and 3 of these didn’t move until late April or early May, at which point their batteries died. The fourth appears to have been an “outlier”, possibly a late-arriving migrant to the Cordillera Central that moved 3.5 km between 30 November and 10 December, another 8.5 km between 10 and 20 January, then was sedentary until 20 April, when it again moved 3.5 km and remained 2 days before its battery died.

With the Mansfield toll road due to reopen this week, just in time for VCE’s 7th banding session of 2022, our hopes are high for a few more backpack recoveries (25 total or bust). Without question, we’ve gained a newfound respect for backpack-toting BITH. In fact, the mind boggles to contemplate female #2821-79107 spending 4 months in Mansfield’s fir forests to raise a brood, undergoing her energy-intensive annual molt, preparing for migration, navigating the arduous southward journey to end up in a patch of Dominican cloud forest at 2,500 m altitude for 6 months, then winging back north to the very same patch of Vermont montane forest and beginning the cycle again! Did I mention that she accomplished all this while lugging a 1.1-g backpack? That extraordinary feat lends some stark perspective to the 5.5-km backpacking “heroics” that VCE achieved last week…

Team VCE, none the worse for wear, ready to descend Mansfield from our ridgeline banding site on 7 July, after a productive overnight session. © Nathaniel Sharp (who actually changed his t-shirt…)

Interesting and graceful report, as always. Thank you.

Such exciting stuff!

Thanks to the VCE intrepid Team! You do amazing work!

And, thanks for the detailed reports!

Martha Pfeiffer

What a story of dedication to this project!

The effort was rewarded with the saw-whets and another GPS pack.

Thanks for your efforts and great narrative.