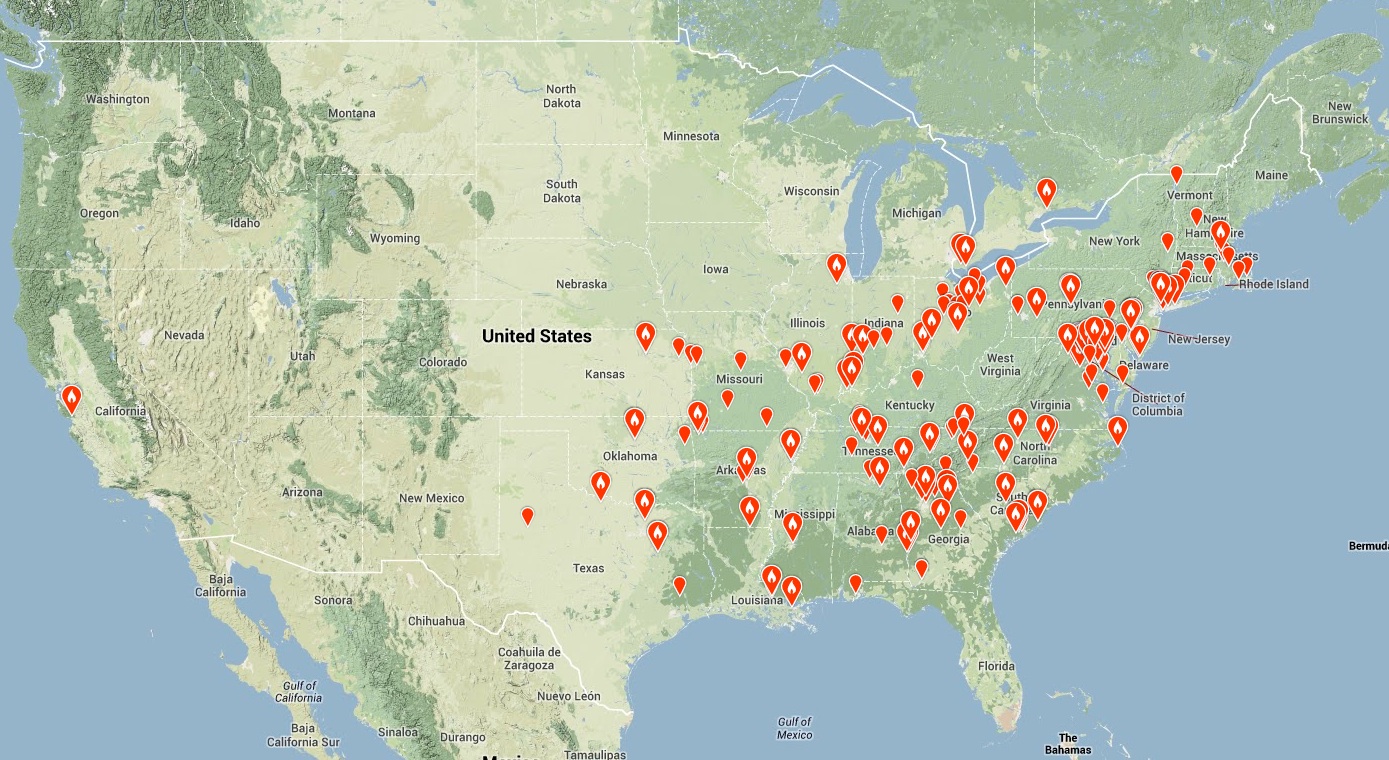

Rusty Blackbird sightings from Opening Weekend of the Spring Migration Blitz, 1-3 March 2014. Data from eBird.

The Rusty Blackbird Spring Migration Blitz is in full swing, and opening weekend was a huge success. Birders from all 23 southern Blitz states scoured the landscape for this elusive songbird, despite snowstorms throughout much of the East. With partners like the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service working hard to publicize this event, word about this under-recognized species is spreading and birders are rallying to conserve a vulnerable songbird.

The Rusty Blackbird is one of North America’s biggest conservation mysteries. Why did this species lose up to 95% of its population across five decades? And given this dramatic and rapid decline of a once-common species, why did no one notice this alarming trend until very recently?

Garnering support for conservation is a much easier task when an initiative is represented by an attractive species. Known as “charismatic megafauna,” cuddly giant pandas, beautiful and majestic tigers, and dignified bald eagles catch the public’s eye and generate sympathy and attention. Although animals do not have an inherent conservation value based on appearance or “likeability,” widespread public support is more easily generated to save an African lion than to conserve a “little brown bird” like the Bicknell’s Thrush or an “ugly” or “disgusting” insect such as the American Burying Beetle. (Actually, both Bicknell’s Thrush and American Burying Beetles are quite spectacular, but those are stories for another day.)

But Rusty Blackbirds face a more insidious challenge. Black birds in general experience an odd yet deep-rooted prejudice; they are often portrayed as evil (think of the crow scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds”) or as harbingers of overwhelming sorrow or death (Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven” is a spooky example).

Crows, ravens, magpies, and blackbirds are often represented as destructive in mythology across the world. In many religions, blackbirds symbolize the devil or damnation. Beyond religious or cultural associations, blackbirds simply have a bad reputation among many amateur bird enthusiasts. Backyard birding websites such as SongbirdGarden.com offer tips on getting rid of blackbirds, grackles, and starlings. While European Starlings are not native to the U.S. and carry the stigma of an invasive species, such a strong objection to native birds is unusual. In fact, scientists speculate that one reason the Rusty Blackbird decline went unnoticed for so long is that this species was considered “just another blackbird” and therefore must be both common and resilient.

We recently posted a collage of four bird species on the Rusty Blackbird Spring Migration Blitz Facebook page: a Brown-headed Cowbird, a Rusty Blackbird, a European Starling, and a Common Grackle. Beginner birders frequently have difficulty distinguishing between these species, and our collage aimed to educate Blitz participants on common Rusty Blackbird look-alikes. Surprisingly, this collage garnered some fascinating backlash that epitomizes one of the Rusty Blackbird conservation challenges. One individual commented, “I call them ‘Nasty’ birds… they devour the sunflower seed… and there are hundreds of them on my feeders… ugh.” Another individual replied, “I don’t know anything about rusty blackbird’s, but I agree with [the above comment]. My term for these are ‘non-birds”, along with English sparrows. I can’t help it, I’m a bird snob!” A third comment reads, “These birds are not welcome at my feeders.”

Many black birds have evolved traits that may seem bad or immoral, when anthropomorphized and judged by human standards. Brown-headed Cowbirds are nest parasites, laying eggs in other species’ nests. These eggs produce chicks that out-compete their “adopted siblings” and exhaust an often-smaller parent. Common Grackles often feed in flocks and “bully” other, more attractive species away from feeders. Crows may kill and eat smaller birds. But this is evolution, not immorality. Animals are not “good” or “bad,” they simply fill the niche they have evolved to fill and use strategies to maximize their survival. And without that species to fill its niche, an entire ecosystem may be thrown off balance. Many blackbird species consume both insects and seeds, eating habits that can serve to control insect populations or weeds. Blackbirds are often considered crop pests, since large flocks can decimate a field’s yield, but conversely, this species also serves to reduce crop insect infestations.

In his Round River: From the Journals of Aldo Leopold publication, naturalist Aldo Leopold stated, “To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.” Each species represents a piece of an overall puzzle, and the puzzle relies on the balance between its parts. If we support conservation efforts only for species that we find inherently likeable, we risk disturbing the delicate balance of the ecosystems we value.

So please join us in our efforts to support the underdogs (or underbirds, if you’ll forgive the terrible pun) of conservation. And revile the blackbirds- Nevermore.

Dr. Judith Scarl is a conservation biologist at the Vermont Center for Ecostudies and a member of the International Rusty Blackbird Working Group steering committee. She coordinates the Rusty Blackbird Spring Migration Blitz, a three year, international initiative to learn more about Rusty Blackbird northward migration. To learn more about the Blitz, visit our website: http://rustyblackbird.org/outreach/migration-blitz/ or follow “Rusty Blackbird Spring Migration Blitz” on Facebook.

Comments (3)

Pingbacks (1)

-

[…] much imagination to guess how “Jim Crow” got its name.) Ecological centers have even linked the dramatic and largely unnoticed decline of blackbirds in North America to this […]

Excellent post!

Thanks, Hillel!

this image is definitely the top notch!