Field Guide to June 2018

Showy Lady’s Slipper (Cypripedium reginae) at Eshqua Bog in Hartland, Vermont. Easy access via a boardwalk makes this location a popular June stop. / @ K.P. McFarland

Here in Vermont, we dream of June during the darkest days of winter. Verdant wooded hillsides glowing brightly under a robin egg sky. Warm afternoon breezes rolling through the valleys as we lounge by clear waters. The chorus of birds waking us each morning. Butterflies and bees skipping from one flower to the next. We often forget about the clouds of black flies, the hum of the mosquitoes and the rainy days. June is a dream here. Its days last forever. Here are some natural history wonders for the month from the Green Mountains.

Loon Language

Perhaps one of the most fascinating things about loons is their haunting and variable voice. Loons are most vocal from mid-May through June. They have four distinct calls which they use to communicate with their families and other loons.

The Mournful “Wail” – An “ooohh ahhhh” is often the sounds of loons identifying or calling to each other; it can also signal initial signs of a mild disturbance.

The Laughing “Tremolo” – A trill or series of trills can be a sign of distress or alarm, and occasionally excitement.

The Crazy and Wild “Yodel” – This is the male territorial call, usually directed at unwelcome loons. Every male has a distinct yodel and transmits much information through the yodel – from how big the male is to his motivation to defend.

Hoots and Coos – On a quiet evening you can hear the loon family or group of loons in a “social gathering” communicating to each other.

Listen for loons and be sure to report your sightings to Vermont eBird, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life, and help us track their populations.

COWBIRDS BEING COWBIRDS

Even devoted birdwatchers find it tough to love the Brown-headed Cowbird. Black body. Fat head. Grating voice. And the female is a homely gray. Not exactly a glamor couple. But appearance is only part of the cowbird’s PR problem.

What most disturbs some birders is cowbird breeding behavior, which biologists call “brood parasitism.” Cowbirds build no nests of their own. After having indiscriminate sex, females wander the landscape laying eggs in the nests of other songbirds, leaving the unwitting foster parents to raise the cowbird chicks.

This doesn’t always turn out so well for the host family. Cowbird chicks exercise brutal sibling rivalry. They tend to grow faster and larger than their adoptive siblings, gaining an edge in gobbling the food delivered by parents. During the melee at feeding time, cowbird chicks might stomp on and smother nestmates. They sometimes even push eggs or chicks out of the nest.

The most poignant evidence of all this comes after the cowbird fledges. Birders occasionally encounter an elegant songbird – a northern cardinal, a chipping sparrow, or a yellow warbler, for example – feeding a hulking cowbird chick out of the nest (see photo). It’s like a human mom with triplets feeding a fourth who happens to be an NFL linebacker.

But let’s give cowbirds their due. After all, cowbirds are simply being cowbirds. Like the rest of us they’ve adapted to changes in the landscape. Read more in an essay from VCE Research Associate Bryan Pfeiffer published in Northern Woodlands magazine.

FLYING TIGERS

And you thought you had trouble telling one butterfly species from another. Lepidopterists – scientists who study butterflies – have been tripped up by tiger swallowtails for centuries.

The tiger swallowtail butterfly, a rather large, yellow butterfly with black tiger stripes. Each spring and early summer they flutter over the hills and valleys of eastern North America, sometimes in great numbers. But figuring out exactly what is, and what is not, a tiger swallowtail has baffled lepidopterists for more than three centuries.

The tiger swallowtail was the first butterfly to be painted by an artist from the New World. John White painted one on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, in 1587 while serving as the expedition leader of Sir Walter Raleigh’s third trip to America. Despite exaggerating the wing shape, his details were relatively accurate.

Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomic naming, called the species Papilio glaucus in 1758. For over 150 years thereafter, it was commonly known as the tiger swallowtail. But Linnaeus had actually named the tiger swallowtail from a black-colored female – a rarer version of the group that looks just like the more common yellow females, except that the background color is darkly pigmented. These dark females generally occur from Massachusetts to Florida, the southern portion of the butterfly’s range.

Why are there dark-colored females? They are thought to have evolved to mimic the dark color of the foul-tasting and poisonous pipevine swallowtail butterfly. This is called Batesian mimicry, when one otherwise palatable species evolves to closely resemble an unpalatable cousin.

Linnaeus also observed the more common, yellow-colored female tiger swallowtail but decided it was another species altogether. A contemporary of Linnaeus documented a male tiger swallowtail, which is also yellow, but decided it, too, was its own species.

In the 1800s, biologists realized that the three species were only differentiated by color and lumped them together under the common name, “eastern tiger swallowtail.” Starting in at least 1906, however, lepidopterists noticed that the more northern populations were smaller and had slightly different markings. Some began recognizing this as a subspecies of the eastern tiger swallowtail and called it canadensis.

In 1991, biologists from Michigan State University announced that they had enough evidence to declare canadensis a separate species altogether – the Canadian Tiger Swallowtail. Their evidence included genetic differences, color and size differences, caterpillar food-plant use, lack of black-colored females in canadensis, and only a very narrow hybrid zone between the two species. It is now widely accepted that Eastern Tiger Swallowtails are found southward and Canadian Tiger Swallowtails are found northward.

The range of the Eastern Tiger Swallowtail just barely makes it into Vermont and New Hampshire. Most of the tiger swallowtails we see around here, therefore, are Canadian Tiger Swallowtails.

Generally, Canadian Tiger Swallowtails are flying around from the beginning of May until the end of June (later in higher elevations), while Eastern Tigers fly from June into October. So if you see a tiger swallowtail sailing over a meadow from mid- to late summer, it just might be an Eastern. But even up close, they look very similar. The Eastern is larger, with the underside marginal forewing band broken into yellow dots separated by black borders. On the underside of the Canadian hind wing, the black line nearest the body is very wide. Minute details for sure. Even worse is that, in the hybrid zone between species, there are many that appear intermediate. In Vermont and New Hampshire, we are in the thick of the intermediate zone.

But the story doesn’t end here. In 2002, another potential tiger was described by two lepidopterists, Harry Pavulaan and David Wright. “When it became apparent that there were inconsistencies in the natural history of mountain populations versus lowland populations of tiger swallowtails, an intensive effort was made to study the field biology of the mountain populations,” said Pavulaan. They have named it the Appalachian Tiger Swallowtail and affectionately refer to it as “Appy”. So far, it is known only from the central and southern Appalachian Mountains.

Appalachian Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio appalachiensis) at the Great Smokey Mountain NP -Oconalluftee Visitors Center. / © K.P. McFarland

Why do tiger swallowtails come in so many varieties that biologists have been trying for centuries to pin them down? Probably because tiger swallowtails have what are known as sibling species – two or more populations that are reproductively isolated from one another yet so similar in outward appearance as to be lumped together even by experts. Careful, intense study of details such as anatomy, biochemistry, and behavior can bring sibling species to light. But there can be many dead ends and tricks that confuse biologists.

If you want to wade into world of tiger identification, now is the time. The lovely Canadian Tiger Swallowtails are flitting over meadows near you. And be sure to add your observations to our site, e-Butterfly.org.

The Hidden Life of Jack

Neither bright nor showy and often hidden under broad leaves, you can easily miss the green and purple pulpit holding Jack, the spathe and the spadix in botanical parlance. Typical of the Arum family, the spadix is covered with tiny flowers hidden deep down in the spathe. With a strange looking flower like this, who is the pollinator that dives deep within?

Tiny flies, called fungus gnats, are attracted to the smell and heat of a male Jack-in-the-Pulpit flower. The flies drop down into the spathe only to become trapped. Pollen clings to them as they search for an escape route. Finally, they escape through a small space in the bottom of the spathe and fly away. Their next stop might be another nearby Jack-in-the-Pulpit, but this time they enter a female flower. There is no escape hatch at the bottom of the spathe. The flies bounce about trying in vane to escape and in the process they drop pollen onto the pistol of an inflorescence.

Jack-in-the-Pulpit grows very slowly in the shaded forest understory. It may take a plant a couple of years to garner enough energy to produce a male flower. After a few years as a male they may have enough energy stored in the corm, an underground stem where the plant stores starch, to grow a female flower and set seed. Depending on soil and light conditions, it may take a seedling up to three years to form a flower. After a few more years it may be able to grow a flower with both male and female inflorescence. The male flowers mature and pass before the female flowers to avoid self-pollination. If the growing conditions have been good when it is about 20 years old it may finally produce female flowers. But if at any time conditions become poor, it may revert back to less energy costly male flowers again. Some of these plants can live to be 100 years old.

Caution, this plant is poisonous. The entire plant contains calcium oxalate, the stuff you find in many meat tenderizers. These needle-shaped crystals are found in specialized cells throughout the plant and can even bother some people who simply touch a broken part of the plant. Calcium oxalate causes an intense burning sensation if ingested. It literally tenderizes your mouth. Also called Indian Turnip, Native Americans dried the corms to make them safe for eating. But there is something in the woods that eats it raw without apparent harm.

I was passing through a large wet area in a rich hardwood forest a few years ago when I came across a place that was pocked with diggings in the mucky soil. It didn’t take me long to realize that each pit had bits of Jack-in-the-Pulpit left scattered about. Black Bears love to eat Jack-in-the-Pulpit and they had recently paid this patch a visit. What would turn our tongues raw doesn’t seem to bother the bears at all.

AVIAN INFIDELITIES

Blackbirds do it. Chickadees do it. Even educated emus do it.

Some birds are cheaters. Their trysts, dalliances, one-morning stands, and other infidelities would constitute a racy script for a wildlife soap opera.

But first, the faithful: In the vast majority of bird species, one male and one female unite for the purpose of raising young. In this classic form of monogamy, or “single marriage,” the pair stays together either for a single breeding season (the case among most songbirds) or for as long as they both shall live (in geese, gulls and swans, for example).

Among the rest (or the restless, as the case may be), polygamy, or “many marriages,” ranges from casual to calculating. Read more in a blog post from VCE Research Associate Bryan Pfeiffer.

A GEM, A TEASE, AND A TRAP

Showy Lady’s-slipper (Cypripedium reginae) after a rainstorm in Eshqua Bog, Hartland, Vermont. / © K.P. McFarland – www.kpmcfarland.com

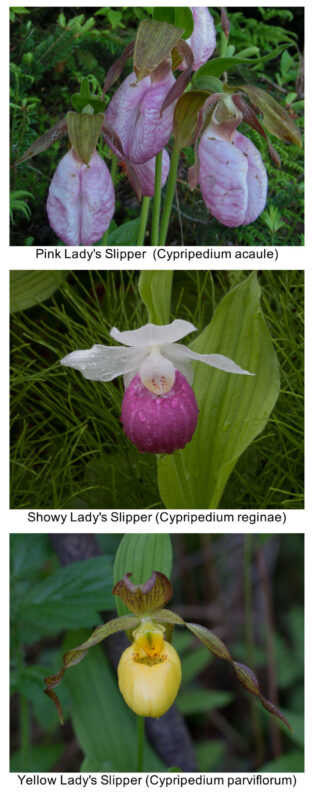

There are about 47 species in the orchid genus Cypripedium, the Lady’s Slipper. Lucky for me three of them bloom within just a short distance from my house. Yellow and Showy Lady’s Slippers grow in a nearby fen and the more upland, acidic loving Pink Lady’s Slipper can be found in mixed pine woodlands.

Gems of the forest to me, but just a tease and a trap for pollinators. There is no edible reward for their pollinating help. The beautiful pigmentation and scent entices insects to enter the flowers down through the labellum, the irregularly shaped petal that forms the “slipper”, of the Showy and Yellow Lady’s Slippers. Unlike most Cypripedium, insects enter the Pink Lady’s Slipper through a slit that runs the length of the labellum. Either way the insects become trapped in the slipper without any nectar and soon begin to move around wildly trying to find an escape route.

Pollen grains are stuck on structures called pollinia. These are behind a shield near the opening called the staminode. When the insect enters the flower, it cannot come into contact with the flower’s own pollen. This prevents self-pollination. To escape, the insect exerts pressure on the stigma creating a larger escape hatch. If it has pollen grains on its body from a previous flower, they are likely to stick to the stigma. The only passage to freedom from there is past the pollinia where a sticky mass of pollen will adhere to its body on the way out. With luck, it will visit another Lady’s Slipper to transfer the pollen. But after a few visits to these flowers, they usually catch on that there is no nectar reward inside the flower and begin to avoid Lady’s Slipper flowers. This might explain the low seed set for these orchids.

Who are the pollinators for these deceptive flowers? A study of the population of Showy Lady’s Slippers near my house found that over 90% of the pollination was done by hoverflies with a minor contribution from flower beetles. Others have found leafcutter bees visiting the flowers.

Recently, Martha Case and Zachary Bradford from the College of William and Mary came up with an ingenious method for discovering visiting pollinators. They used a piece of ribbon and a clip to block the escape passage from the slipper. They found a near threefold increase in pollinator detection in Yellow Lady’s Slippers. Ten bee species from four families (Andrenidae, Apidae, Halictidae and Megachilidae) were found in the flowers (read more about the study).

For an insect, beauty is indeed only skin deep when it comes to the Lady’s Slippers.

Beautiful photos……………

When I was a child in the 50’s i was told it was illegal to pick lady slippers and some other plants I can’t remember. Illegal I now think not. Was it?