October is a month of change. The forested hills fade from green to a kaleidoscope of red and gold that dazzles the eyes. Here’s your field guide to some moments that you might not otherwise notice during these few precious weeks that feature colored hills beneath a deep blue sky, with the calls of migrating geese high overhead and the last Monarchs gliding silently southward.

A FALL FLOWERING TREE attracts COLD TOLERANT MOTHS

The yellow streaming blooms of Witchhazel (Hamamelis virginiana) can be found in the understory in October when most leaves have fallen to the ground. The long, bright-yellow petals, sweet smell of nectar with pollen loaded stamens near the source, suggest that insects are the mode of pollination. But with the cool temperatures, most insects are finished for the season. Who visits this late bloom?

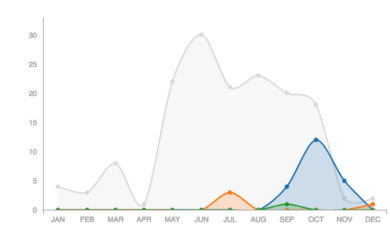

Witchhazel phenology from the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist. Blue are those observations that reported flowering.

No one really knew until University of Vermont biologist and naturalist Bernd Heinrich discovered that a group of Owlet moths feed at the flowers on late evenings in October and likely are the main pollinators. Because it is often cool (or downright cold) on October nights, moths need sugars to fuel the high body temperatures (~86° F) that are necessary for flight. These sugars mostly come from tree sap at this time of year, but nectar, if present, would suffice too.

When the moths are at rest, their body temperature falls to the air temperature around them and they enter a state of torpor. During daytime when temperatures fall below freezing, they hide under insulating leaves on the forest floor. But when night falls, they have to fly to find food and mates, which requires raising their body temperature—maybe by as much as 50° F—to activate their flight muscles. To do this, they shiver. On long flights they will sometimes repeatedly stop and shiver to warm up again. All of this is powered by the sugars they consume.

In a 1987 Scientific American article Heinrich wrote, “Adult winter moths generally feed on the sap of injured trees, although on late-fall nights a few years ago I saw many of them feast on the blossoms of witch hazel, Vermont’s latest-blooming plant. Until that time no one knew just how the plant was pollinated.”

The moths that pollinate Witchhazel are several species of Owlet moths (Family Noctuidae), including (click to learn more at iNaturalist):

- Grote’s Pinion Moth (Lithophane grotei)

- Morrison’s Sallow (Eupsilia morrisoni)

- Three-spotted Sallow (Eupsilia tristigmata)

Add your observations to the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist and help us track Witchhazel flower phenology and some of the insects you might find visiting the flowers.

Zombie Leaves

They might appear dead. But they are not quite dead. They are the undead: zombie aspen leaves. Find them as you walk the brown autumn paths—yellow leaves with a patch of green tissue radiating from the base of the midrib. Here in Vermont, these are mostly Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides), but you can also find the green on Big-toothed Aspen (P. grandidentata) and, rarely, Eastern Cottonwood (P. deltoides). VCE research associate and naturalist Bryan Pfeiffer shared his discovery of the nearly dead leaves a few years ago. It wasn’t until he put a leaf under a dissecting microscope that he found it to be less zombie than something from the film “Alien.” The beast lies within! Read the whole story from Bryan on the VCE Blog.

Fall Leaf Phenology

Mount Mansfield after a late autumn snow shower. / © K.P. McFarland

We’ve all learned the basics of how and why leaves change color in the fall. But on this edition of Outdoor Radio, we take a deeper look at the chemistry of fall foliage and take leaf peeping to a whole new level. We meet Joshua Halman, a Forest Health Specialist with the Vermont Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation at Underhill State Park, where a fresh autumn snow has fallen overnight. The department has monitored these trees for 25 years, recording color change and leaf drop here and at other places around the state.

Halman reports that this work has documented the impacts of climate change. “Seen over this time, the peak color and the main time for leaf drop has actually become later,” Halman explains. “What we’re seeing since we started recording our fall phenology data is that, on average, foliage is peaking about eight days later over that 25-year period.”

Listen to the show

You can find more information at the Vermont Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation’s Forest Health Monitoring page.

Turn Red Before You’re Dead

Why on one hillside do the trees have muted autumn colors, while nearby on another they are radiant red? Recent research might shed some light on this puzzling question.

There are four basic colors in fall leaves and a different pigment produces each. Xanothophylls is responsible for yellow, carotenoids for orange, tannin for brown, and anthocyanids create red and purple tones.

During the growing season green chlorophyll in tree leaves is broken down by sunlight and constantly replenished. As day length decreases the abscission cells, a special layer at the leaf-stem junction, divide rapidly and slowly block transport of materials. As abscission begins, chlorophyll production wanes and eventually stops.

As the green chlorophyll breaks down without replacement we begin to see the underlying orange carotenoids and yellow xanthophylls. These pigments help capture light energy during the growing season. But unlike yellow and orange pigments, red anthocyanins are made during fall leaf senescence. It is manufactured from sugars found in the leaf. They produce greater amounts during cooler nights and sunny days. When a hard freeze comes along, production ends.

Why would a tree use energy to make a pigment in a leaf that is about to die and fall off? In 2003 William Hoch, a biologist at Montana State University, found that if he genetically blocked anthocyanin production, the leaves were much more vulnerable to fall sunlight damage, and so sent less nutrients to the plant roots for winter storage before the leaf fell. The tree was not able to recuperate as much energy back from the leaves it grew earlier in the year.

A few years later, University of North Carolina at Charlotte graduate student Emily Habinck found that in places where the soil was lower in nitrogen and other important elements, red maple trees produced more anthocyanin in the leaves. Apparently trees growing in more stressful environments invest in more anthocyanin, which allows them to recover more nutrients that are stored in the leaves before they fall. Bright red leaves under a clear blue sky are spectacular to see. But what is beauty to us may be survival to a tree.

Should I stay or should I go Now?

Sharp-shinned Hawk about to be released after it was banded and a sample of blood taken for analysis of mercury levels. / © K.P. McFarland

The autumn river of raptors migrating southward becomes dominated by Accipiters like Sharp-shinned Hawks in October. Although not all individuals leave, many do. More than 11,000 Sharp-shinned Hawks were seen on one October day at Cape May Point, New Jersey as they pushed southward. Most overwinter somewhere in North America; however, some travel as far south as Central America, migrating thousands of miles between their breeding and wintering grounds. They are powered by a mix of flap-gliding flight and soaring on mountain updrafts and rising plumes of hot air. Recently, more Sharpies have been overwintering farther north. No one knows exactly why, but the popularity of backyard bird feeding may provide some Sharp-shinned Hawks the food they need to survive northern winters.

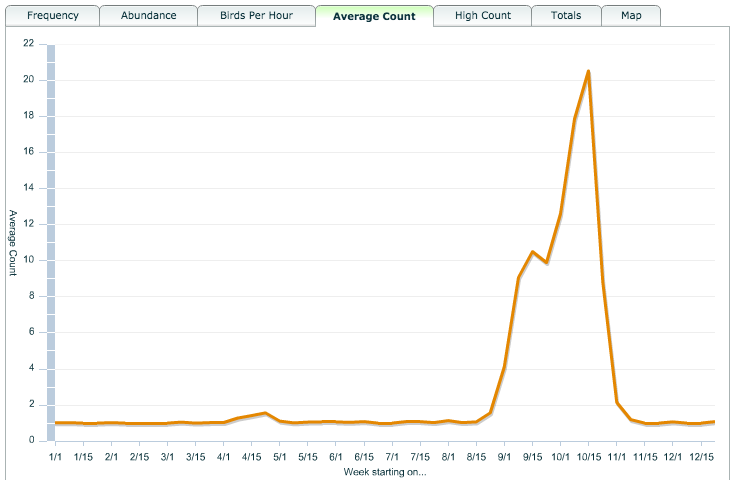

Observations of Sharp-shinned Hawks reported to Vermont eBird. You can help track these and other birds by reporting your sightings, too.

Sharp-shinned Hawk populations currently appear stable, after dramatic declines during the DDT pesticide era (mid-1940s to 1972). Recently, work by VCE has shown that individuals nesting in Vermont’s Green Mountains and a rare subspecies in the mountains of Hispaniola, have high levels of mercury in their blood. Learn more from VCE’s Research Notes about this finding.

Moose on the Loose

The largest land mammal in the region, averaging 1,000 pounds and standing six feet at the shoulder, an adult moose can be surprisingly fast (~35 mph for short distances). Despite being nearsighted, moose have keen senses of smell and hearing. And during the rut season, they can be cranky and dangerous, too.

The breeding season, or rut, extends from mid-September through mid-October. Both bulls and cows travel more during this season in pursuit of a mate. The bull stays with the cow only long enough to breed, then he leaves in pursuit of another cow.

Only bulls grow antlers each spring. After the rut, they shed them, starting in November. Bulls also have a larger flap of skin and long hair that hangs from their throat, called the bell. It is thought to be what is called a secondary sexual characteristic. It may be used for communication during the rut, both by sight and smell. During the rut a bull will rub the cow with his chin, also called chinning, and the bell transfers the bull’s scent to the female. Another possibility is that the size of the bell may be an indicator of dominance and health to other bulls or cows, just like the size of the antlers are.

Moose populations in Vermont and New Hampshire have undergone a rapid decline for a variety of reasons, including Winter Ticks. This past spring, Outdoor Radio joined Jake Debow, a graduate student at the University of Vermont and biologist with Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department, to trek through deep snow near Maidstone Lake in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom to find out more about the plight of moose in the region and ongoing research and monitoring efforts. Debow and the rest of the team has collared over 90 moose to help them understand mortality rates, productivity, and health. Listen to Outdoor Radio as they track a cow and her calf and attempt to get urine samples to provide researchers with clues to their nutritional health and learn what might be changing moose populations across the region.

Nice…………….You must be getting writers cramp.

Haha. In the brain!

So great to read that all this research is ongoing! I live in Wolcott on 120 acres and have suffered a sharp decline in moose population. Last winter I followed a moose trail only to see next to each hoof print a drop of blood.

I wish VT Fish and Wildlife would eliminate moose hunting and concentrate on tick control. Hate to see the moose suffering and dying off.