It can happen almost anywhere. On a cool morning after a storm, for example, when fall warblers drop from their nocturnal migratory flights into your backyard. Or on some summit with Broad-winged Hawks kettling above and insects like Monarchs and Green Darners gliding southward. Or even at night when you step outside and hear a few contact calls high above from songbirds as they migrate southward on the latest cold front. And then one September day, you are finally convinced that summer is indeed over and you embrace autumn. Here is your field guide to life on the move, and a few other natural history tidbits for September.

What is Wrong with the Maple Leaves?

You may have noticed in some areas that the leaves on some maple trees are a mess – mottled brown with round holes pocked throughout. This is the work of the tiny Maple Leafcutter Moth (Paraclemensia acerifoliella). Grab a leaf and take a closer look. The caterpillars feed on the leaves of maple and sometimes birch. Larvae feed as leafminers for about 2 weeks and then the caterpillars cut two circular pieces of leaf and sew them together into a portable case to continue to feed. If you carefully peel one apart, you can see the tiny larva feeding inside.

Maple Leafcutter Moth (Paraclemensia acerifoliella) caterpillar found inside its leaf shelter. / © K.P. McFarland

Soon, these caterpillars will be full grown and fall to the ground in their leaf cases. They will spin a silk cocoon and pupate. They remain encased until spring when they emerge as adults.

An adult Maple Leafcutter Moth (Paraclemensia acerifoliella) shared with the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist.

A native species, this moth sometimes has large population outbreaks. A significant outbreak of maple leaf cutter hit Quebec in the 1960s and Vermont in the 1970s. Recently, there have been periodic outbreaks, with the level of damage varying from year to year and place to place. You can add your observations of this moth and help us track it at the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist.

Migrating Squirrels?

Have you noticed? Keep an eye out on your drive. It appears that both Red Squirrels and Eastern Gray Squirrels are on the move. I have seen many of them scurrying along, and sadly, many laying on the edge of the road. Migration can be dangerous.

Last year was a fantastic year for tree seeds here in northern New England. White Pine, Maple, Ash, Oak, and others had a huge crop of seed (called mast). And with a huge crop of seed comes large litters of seed predators – mice and squirrels. But like all bull markets, the bountiful harvest came to and end. Now, a year later, the squirrels are on the move to find food elsewhere.

Historically, Eastern Gray Squirrel migrations were a site to behold. The great biologist Ernest Thompson Seton wrote in the Journal of Mammology in 1920 that “These migrations are now a thing of the past, so that we can but piece together the accounts of the earlier naturalists…” He gathered and relayed a great many accounts, including some from Vermont “Doctor Bachman states that in the autumn of 1808 or 1809 great hordes came from the west into northern New York and Vermont…” Or nearby on the Hudson River where “they swam the Hudson in various places between Waterford those which we observed crossing the river were swimming deep their bodies and tails wholly submerged; several that had been carried downwards by the stream, and those which were so fortunate to reach the opposite bank were so wet and fatigued…”

Red Squirrels were noted for large migrations historically too. For example, in the 1884 book, Mammals of the Adirondack Region, the author quotes an account from the history of Essex County. “The autumn of 1851 afforded one of the periodic invasions of Essex County. It is well authenticated that the red squirrel was constantly seen in the widest parts of the lake [Lake Champlain] far out from land, swimming towards the shore as if familiar with the service.”

Naturalist and writer Ted Levin noted on the local bird e-mail group recently that “seven years ago, nine months after mast drop, gray squirrels in the Champlain Valley were on the move.” Road kills were common on the main highways. Levin says that, “In fact, I watched several swim across Lake Champlain. One, struggling in the wind and wind driven current, drowned as I watched. Another on the shoreline was so exhausted from the swim I could have picked it up.

Which brings us to present. There now appears to be a movement happening right now. Local naturalist and birder Dave Merker noted his observations recently on the bird e-mail group. “I just drove to Charlestown and back. It appeared to me to be lots of dead gray squirrels on 91. They could be on the move.” Keep a watchful eye during your travels and report any movements you observer, no matter how big or small, to the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist and we can see if we can piece together what is happening and where.

Dragons Flying Southward

Dragonfly migrations have been observed on every continent except Antarctica, with some species performing spectacular long-distance mass movements. The Wandering Glider is the global insect long-distance champion, making flights across the Indian Ocean that cover twice the distance of Monarch butterfly migrations. In North America, dragonfly migrations occur annually in late summer and early fall, when thousands to millions of insects move from Canada down to Mexico, Florida and the West Indies, passing along both U.S. coasts and through the Midwest. North America may have as many as 18 migratory dragonfly species; some engage in annual seasonal migrations, while others are more sporadic migrants.

North America’s best-known migrant dragonfly is the Common Green Darner. This species appears at northern latitudes in early spring, often before any local dragonflies have emerged. These early returnees are migrants from the south, having flown from perhaps Florida, the Caribbean, or Mexico. They breed soon after arriving, and their nymphs develop quickly in wetlands warmed by the summer sun. Many adults emerge in August; instead of maturing and breeding at their natal site, they begin a southward movement that may span a month or longer. Their destinations are currently unknown, but presumed to be the same areas where spring migrants are believed to originate. Migrating individuals may breed at their final destination or at sites along the way.

Although migration is a common phenomenon in Common Green Darners, it is not obligatory. Populations in more northern areas are known to consist of both resident and migratory individuals. These phenotypes overlap in space, but exhibit strikingly different annual phenologies that appear to limit temporal overlap in breeding. Migrants arrive at breeding ponds in March – April, and larvae emerge as adults after 4-5 months. Resident darners begin their breeding cycle a month or two later in June – July, and their larvae overwinter in natal ponds, finally emerging as adults in May-June of the following year.

There is evidence that water temperature plays a role in maintaining this phenotypic variation. Final-instar larvae of migratory phenotypes reared in the laboratory required a minimum water temperature of 8.7 C to develop into adults. In Ontario, resident phenotypes required 20% more accumulated degree-days than migrants to complete larval development. These thresholds suggest that the relative size of migratory populations could vary with latitudinal gradients and associated temperatures.

Migrant or resident, if you spot a Common Green Darner, or any dragonfly for that matter, add your observations to the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist to help us document their phenology.

Epic Bird Migrations

They travel by night across vast stretches of land and sea. They navigate using mental star charts, magnetic fields, angles of ultraviolet light emitted by the setting sun and invisible to us, familiar landscapes, and perhaps other seemingly magical methods. Written into poetry, painted on canvas, studied by scientists, and loved by birders – the marvel of bird migration is shared by all of us. There are nearly 10,000 bird species in the world and about half of them migrate. From warblers to waterfowl, hummingbirds to hawks – each has a remarkable story to tell. Here’s a few amazing examples. Oh, and be sure to add all your bird sightings to Vermont eBird and help us track there populations and phenology!

Across the Entire Ocean at Night

Hold two nickels and a dime in your hand. That is about how much a Blackpoll Warbler weighs while it is raising its young each summer. This black-capped songbird nests from the mountain forests of New England across the north woods to Alaska. This is a bird that only knows one season – summer. With frost nipping their toes, Blackpolls move to the eastern seaboard. Those from Alaska will have already flown over 3,000 miles. But, the migration doesn’t end here. This is just a place to check-in for rest and relaxation.

Gorging on insects and berries, they double their weight. “They actually feel soft and pudgy in your hand”, says Trevor Lloyd-Evans, a biologist at Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences who has studied bird migration for over 30 years along the Massachusetts coast using the same kind of nets that captured the thrushes. Fat bulges from throat to the tail and then a cold front arrives from the north.

With favorable tailwinds the birds depart into the darkening southeast sky and sail over the vast Atlantic Ocean. Radar data show migrating songbirds fly at an altitude up to 2,600 feet within four hours after sunset in New England, and rise to 6,500 feet by the time they reach Bermuda. As they approach the Tropic of Cancer, the winds shift to the northeast, allowing for drift toward the Lesser Antilles and South America. Over the Lesser Antilles, flight above 13,000 feet results in lower wind speeds and less headwind than at lower altitudes. They have been recorded as high as 20,000 feet over Antigua. As they approach South America over Tobago their altitude drops to just 2,500 feet. The entire non-stop flight lasts 80 to 90 hours with an averaging speed of 25 miles per hour.

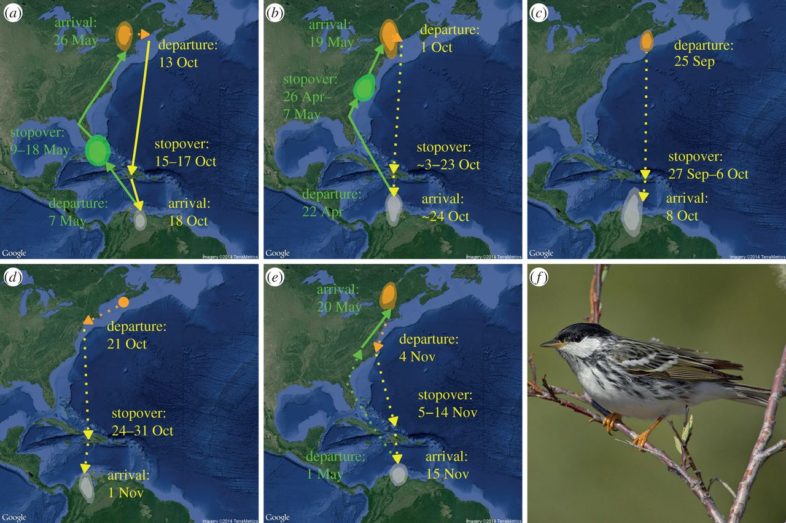

To track the flights, VCE and our colleagues captured warblers here in Vermont and Nova Scotia and fitted them with miniature devices called “light-level geolocators,” which resemble songbird backpacks. The warblers migrated south in the fall, spent a winter in the tropics, then returned in spring to North American breeding sites, where we recaptured five birds, removed their geolocators and downloaded their flight itineraries.

Four warblers, including two from Vermont, had departed between Sept 25 and Oct 21 from points somewhere between western Nova Scotia and western Long Island or New Jersey, and flew day and night over the Atlantic Ocean until landing in either Hispaniola or Puerto Rico. Their flight times ranged from 49 to 73 hours.

A fifth bird, which we had also first captured in Vermont, likely took a shorter trans-oceanic trip. It departed the mainland on November 4 from Cape Hatteras and then flew nearly 1,000 miles non-stop for 18 hours later to land in Turks and Caicos before continuing on to South America.

Blackpoll Warbler migration tracked with geolocators. http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/11/4/20141045?hc_location=ufi

This tiny songbird is fueled entirely by stored fat. Scientists have calculated that a Blackpoll Warbler has to weigh more than seven tenths of a gram to complete the trans-Atlantic flight. For us, “the metabolic equivalent would be to run four-minute miles for 80 hours”, note ornithologists Tim and Janet Williams. “If a Blackpoll Warbler were burning gasoline instead of its reserves of body fat, it could boast of getting 720,000 miles to the gallon!” A Boeing 747 needs about 10 gallons of fuel to fly one mile and a small Cessna travels just 10 miles per gallon.

Humming Along

Perhaps the Blackpoll Warbler hasn’t impressed you. Try removing the two nickels leaving just a dime in your hand. You now hold a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Despite their tiny size these birds fly non-stop across the Gulf of Mexico each spring and fall in 24 hours. Large numbers have been observed flying low over the waves trying to make landfall in the spring. And like the Blackpoll, they pack on fat to fuel the journey, easily doubling their weight. Just add another dime.

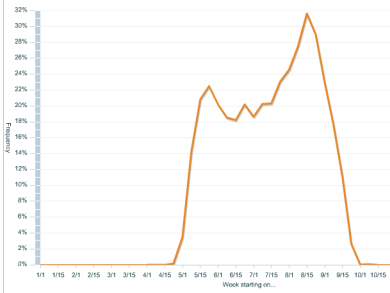

When the flowers stop blooming and insects stop flying, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds head south. Some adult males start migrating south as early as mid-July, but the peak of southward migration is August and early September, and by October they’re all gone.

Most, if not all, of the hummingbirds at your feeders in September are migrants and not the same individuals you’ve watched all summer. Since they all look alike, it’s difficult to know for sure, but banding studies have shown the turnover. It’s not necessary to take down feeders to force hummingbirds to leave, and in the fall all the birds at your feeder are already migrating anyway. Keep them up as long as you can and just maybe a wayward rare species will find them.

Where do they all go? There is some evidence that more of them travel around the Gulf of Mexico in fall migration, rather than cross it as they do in spring. They’ll spend the winter in Mexico and Central America. Weighing a mere two-tenths of an ounce, they’ll make the round trip back in April and delight us once again with their bright colors and active flights after our long white winter.

Shorebirds Flying the Length of the Globe

Few birds undertake a migration as lengthy, arduous, and spectacular as the Hudsonian Godwit. This large, distinctive shorebird was long regarded as one of the rarest species in North America, due to the infrequency with which it was sighted. In the 1940s, biologists discovered large migratory flocks at remote sites along the James and Hudson bay shores.

From its scattered (and still poorly known) breeding locations between western Alaska and Hudson Bay, Hudsonian Godwits undertake a marathon southbound journey that lands them in marshes and coastal mudflats of southern South America. Their route apparently involves a series of long, non-stop flights, punctuated by a very few key staging areas at which they stop to replenish energy stores. The western James Bay coast and several lakes in south-central Saskatchewan are among the most important of these sites. During fall staging they can gain up to one percent of their body weight each day with up to 38 percent of their weight accounted for by fat. Most eastern birds are believed to fly nonstop from James Bay to South America, a distance of at least 3,000 miles. But a handful of sites along the eastern U.S. coast regularly support staging Hudsonian Godwits and their wild-eyed fans – birders.

Gliding by Day to South America

While all of these birds rely on a full tank of gas, the Broad-winged Hawk simply relies on its soaring abilities. This bird doesn’t gorge itself. In fact, it wastes little energy on flapping at all. This hawk, like many others, is a glider. Using rising columns of hot air like an elevator, there can be hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands, in flocks or “kettles” slowly circling upward on a thermal and then gliding southward and downward to catch the next free ride. They rarely, if ever, sail over open water where few thermals exist and they only migrate during the day. Instead, they follow the land as it gets narrower and narrower in Central America, eventually dumping some of them into South America after 40 days of migration.

These champions of migration are superbly adapted for the rigors of long distance flight – air filled bones to lighten the load, large and powerful hearts that are proportionally six times larger than a human heart, enhanced oxygen carrying capacity in their blood, a supercharged respiratory system using air sacs that allow fresh air to constantly bath the lungs, feathers for flight and insulation, specialized pectoral muscles, and more.

This fall, climb a hill and watch the hawks glide southward one sunny day. Or, just before bedtime in a quiet place, go out and listen toward the sky. If you listen closely you will hear the waves of songbirds migrating overhead as they call to each other. Bear witness and wonder to the annual ritual that spans the eons and the globe — the mystery of migration.

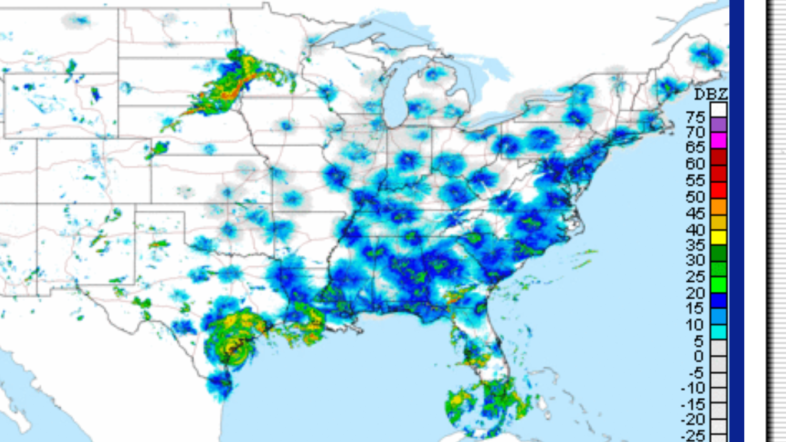

GHOSTS ON THE SCREEN

When radar was first deployed, operators called them “ghosts”, mysterious echoes seen on radar screens on clear nights. Some of these were caused by migrating birds and insects. Since the first units were placed along the Gulf Coast in the 1950s, ornithologists and birders have become increasingly aware of the power of using radar as a tool for understanding bird migration. In addition to detecting and depicting meteorological phenomena, this radar network can be used to watch and to track the movements of birds. And, its available at your fingertips. When a cold front passes through and the winds are from the northwest, visit the NOAA weather radar site on the internet when it becomes dark outside and see if the birds have lifted off and are headed southward. Learn more about radar ornithology from the eBird blog.

MONARCH MIGRATION – SHAPING UP TO BE A BIG YEAR IN THE NORTHEAST

Judging by the observations from around the Northeast, this summer has been a productive year for Monarch butterflies, and it could be one of the best fall migrations here since 2007.

When the hawks are moving, the Monarchs are too. Both ride the air currents southward. The Monarchs barely flap a wing. On days with unfavorable winds, you can often find them fueling on flower nectar, especially in large fields of Red Clover. By the time cold air settles into the Northeast, the Monarchs are well on their way to Mexico.

Each winter in small area in the transvolcanic mountains not far from Mexico City the entire population of Monarch butterflies from east of the Rocky Mountains wait in the trees. These are small peaks ranging from 7,800 to 11,800 feet in elevation and covered with Oyamel Fir trees (Abies religiosa), a species closely related to the Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea) found on the mountain tops here in northeastern North America. In 1984, a study found that there may have been as many as 60 overwintering sites that can be used by the butterflies, but now there are just a few each winter. A site may contain up to 4 or 5 million monarchs per acre and cover as little as one-tenth up to 8 acres of fir forest.The butterflies arrive from the north in November to late December and hang out on the trees metabolizing fat reserves that they have built up during migration. Remarkably, they actually gain weight on migration and arrive on the wintering grounds with fat reserves for the winter, unlike songbirds, which require huge fat stores to burn on migration.

The winter generation lives up to 8 months while the successive spring and summer generations are lucky to live 5 weeks. It takes up to 6 generations of spring and summer Monarchs to produce the final “super-Monarch” that migrates to Mexico in autumn and then back to the southern United States in spring.

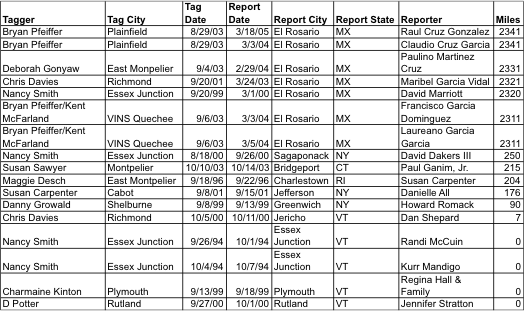

How do we know that at least some Monarchs from the Northeast actually make it to Mexico? Tracing unique chemistry in their wings tells us that about 15% of the overwintering population comes from the Northeast on average. And, we also know directly from Monarch tags. Many of us have been tagging adults during fall migration in cooperation with Monarch Watch. Using small tags like tiny bumper stickers with unique identification numbers on them, volunteers capture and place them on a Monarch’s wing in the fall. With millions of Monarchs, the odds of a recapture are very poor. Here in Vermont we have had a few lucky finds. There have been 7 Monarchs tagged in Vermont and found in Mexico! Maybe you could be a lucky tagger. Anyone can do it. Just visit Monarch Watch for more details.

You can also watch Monarchs virtually move southward on the internet as people like you report sightings to Journey North, e-Butterfly.org, and iNaturalist. Whether you find eggs or caterpillars, see them nectaring or actively migration southward, you can add your sightings to help get a picture of this amazing migration across the continent.

Excellant article and photos.

Love this newsletter. It is deeply informative with great scientific detail. thank you

These field guide posts are always so informative. Thank you!

Wonderful and rich information. A joy to read.