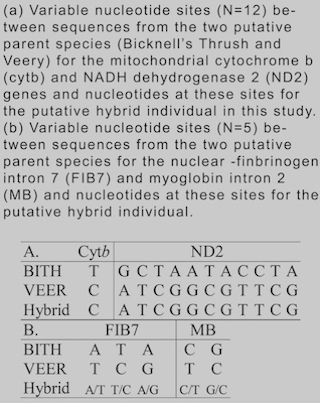

A first-hand account of VCE biologists discovery of a rare thrush phenomena published this month in the Wilson Journal of Ornithology.

I woke before dawn to calm weather on the summit of Stratton Mountain, a perfect morning for Mountain Birdwatch, VCE’s long-term mountain bird monitoring program with survey routes located on high-elevation hiking trails across the mountains of the Northeast from the Catskills to Katahdin. On one morning each June, volunteer citizen scientists and VCE biologists conduct simple counts of 10 montane breeding bird species, such as Bicknell’s Thrush and Blackpoll Warbler. My mission was to hike along a trail and complete five bird survey stations spaced evenly, one after the other, over a mile along the ridgeline path. But on this morning, my mission was unexpectedly aborted.

As I hiked to the first survey point in the dim light, the dawn bird chorus was just starting. Suddenly, off to my right a familiar thrush sang, but in the wrong forest. A Veery, commonly found in the hardwood forests far below me, was repeating his ethereal downward-spiraling song over and over, one of the most seductive of all bird songs. Having studied birds for nearly two decades in these high-elevation Balsam Fir forests, I had not once heard this species singing at these elevations. “Wouldn’t it be something to have this on my Mountain Birdwatch count,” I thought as I quickened my pace to the survey station.

My count began and I quickly listed a Blackpoll Warbler whispering its song nearby, a Winter Wren belting out its long song, the “Sam Peabody Peabody” whistles of a White-throated Sparrow. And there it was again, the Veery began singing just 50 yards away. I added him to my list with a grin.

Veery Song

But then, quite near the Veery was its very close cousin, a Bicknell’s Thrush calling. “How fascinating having these two birds so near each other,” I thought. And at that moment I heard it, the bird let out a long flute-like song with the first half pure Veery and the second half pure Bicknell’s Thrush, rising upward at the end rather than spiraling downward. The Veery and the Bicknell’s were one and the same. I listened in disbelief as the bird switched back and forth between a full Veery and the half Bicknell’s song. I hatched a new mission. Mountain Birdwatch would have to wait.

Strange Thrush Song

I raced back to the ski patrol building, where our crew stayed all summer to intensively study these songbirds, to collect my microphone and digital recorder, a mist net to capture the bird, and some warm bodies to help. Bursting into the building blabbering wildly about a Veery, several of my fellow field biologists interrupted my manic state to say that they had heard the Veery too, a few days prior. But when I told them it sang both songs, they quickly followed me out the door.

The bird continued singing and calling when we arrived. Using my directional microphone and digital recorder, I captured several of its song variations and calls. Meanwhile, my colleagues set up a mist net (a long dark-colored net specially made for capturing songbirds) along the trail. We routinely use bird recordings as lures to harmlessly capture and release Bicknell’s Thrushes, then place tiny, uniquely numbered aluminum bands on their legs to learn about their survivorship as they return, or not, year after year from the Caribbean to breed here. This time, we were laser-focused on this strange thrush.

I placed the recorder with a small speaker beside the net and pressed ‘play’. Within a minute or two, the bird had flown into the net right above the speaker. We tricked him into thinking that another male with the very same song repertoire as his was nearby. I removed our mystery bird from the net and gently placed him in a cloth bag for transport back to our building for closer examination and banding.

Word spread quickly among our team working out in the forest. Chris Rimmer, who was following radio-tagged thrushes somewhere on the mountain, hurried back to the hut, along with Sarah Frey and others. I removed our bird from the bag to exclamations of surprise. It appeared most similar to an eastern Veery. Its back and tail were uniformly reddish brown, but this bird’s breast had much bolder spots and very little brown washed across the white background – more like a Bicknell’s Thrush, or perhaps a Veery from Newfoundland. To our eyes, this bird was an enigma.

We could age the bird as a yearling (hatched the previous summer) from its plumage and its sex as male from its swollen cloaca. We adorned the bird with a shiny new US Fish and Wildlife Service leg band, officially and uniquely identifying him as number 1931-76152. With most of us now convinced that this bird was a hybrid, we fondly named him “Vick”, a combination of Veery and Bicknell’s. There was just one more piece of evidence needed – a blood sample. A small quantity of DNA would tell us if our hunch was correct.

As luck would have it, we were prepared. We collect blood samples from all the Bicknell’s Thrushes we capture to examine them for mercury contamination, genetic analysis, and blood parasites. Just like a pin prick to your finger at the doctor’s office, we insert a tiny needle into a wing vein and capture a drop of blood into a capillary tube. After a few quick photos of Vick, he was ready for release, none the worse for wear.

The Veery x Bicknell’s Thrush hybrid fondly known as “Vick” right before he was released after banding. The light brown centers on the greater wing coverts allow us to age this bird as a yearling. / © K.P. McFarland

With his unique song, over the next few weeks Vick was easy to locate on our study area. I continued to record his songs and calls, convinced more than ever that he was a hybrid. We all agreed, his mother must have been a Bicknell’s Thrush that mated with a wandering male Veery. However, until we obtained DNA results from the blood sample, we could only speculate. Our team needed an avian genetics expert on this case.

Fortunately, we had been collaborating with Ellen Martinsen from the Center for Conservation Genomics at the Smithsonian; she was studying avian parasites in Bicknell’s Thrush blood by screening it for parasite DNA. Ellen enthusiastically took on the challenge to determine exactly who were Vick’s parents.

Evolutionarily, the relationship between Bicknell’s Thrush and Veery, both in the genus Catharus, has been examined and debated for decades. A recent genetic study of Catharus thrushes provided strong support that Bicknell’s Thrush and the more northern Gray-cheeked Thrush were sister taxa, with Veery as their next closest relative. This study estimated that Bicknell’s and Gray-cheeked thrushes diverged from Veery about 800,000 years ago.

Their isolation continues today. Bicknell’s Thrushes nest in the high-elevation Balsam Fir forests of the Northeast and winter in the Caribbean, while Veery usually nest below 2,300 feet elevation in wet hardwood forests and winter in South America. The two species’ partitioning of breeding habitat by elevation and forest type seems to limit the degree of ecological overlap and opportunities for contact during the breeding season.

With blood samples from Bicknell’s Thrush, Veery, and our putative hybrid Vick, Ellen went to work. Our best guess was that his mother was a Bicknell’s Thrush. So Ellen planned to examine mitochondrial genes, which are inherited only from the mother. And…all of the mitochondrial genes aligned with Veery. Against our best guess, Vick’s mother was a Veery! Was this bird really a hybrid after all?

With blood samples from Bicknell’s Thrush, Veery, and our putative hybrid Vick, Ellen went to work. Our best guess was that his mother was a Bicknell’s Thrush. So Ellen planned to examine mitochondrial genes, which are inherited only from the mother. And…all of the mitochondrial genes aligned with Veery. Against our best guess, Vick’s mother was a Veery! Was this bird really a hybrid after all?

Ellen moved on to nuclear DNA, which has the potential to resolve both male and female parentage of an individual, but evolves at a slower rate than mitochondrial DNA and offers a decreased degree of divergence between species, especially for those as recently diverged as Bicknell’s Thrush and Veery. Fortunately the results were clear each of the sites contained both Bicknell’s and Veery material. The results also suggested that Vick was a first-generation hybrid – i.e., the year before our discovery of Vick, a male Bicknell’s Thrush met a female Veery at a location that will remain forever unknown.

The propensity for hybridization varies widely among birds. Some groups lack any record of hybridization while others hybridize more freely, such as wood warblers where more than 50% of species have been reported to hybridize. This isn’t surprising, as hybridization in the wild is most common among closely related species — species-rich groups that have undergone rapid and relatively recent adaptive radiations, or sister taxa like our group of woodland thrushes.

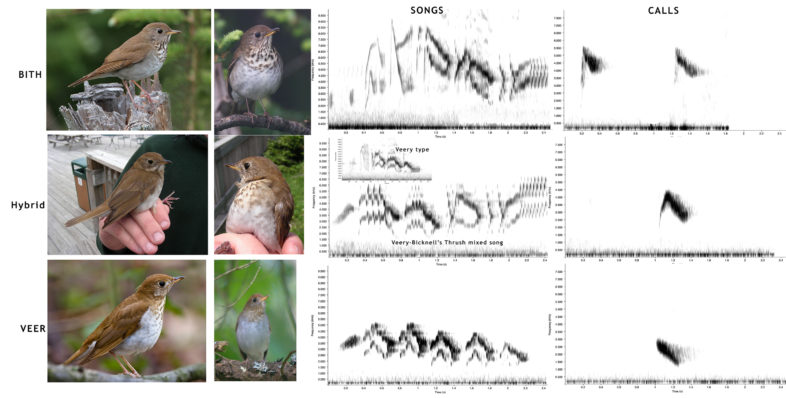

One mystery remained for me. How did this bird learn its unique vocalizations? We found that Vick sang a complete Veery song about 75% of the time and a mixed song that began as Veery and ended as Bicknell’s Thrush just 25% of the time. He only delivered one Bicknell’s song in a given sequence, but would often sing Veery songs in rapid succession. And he only used Bicknell’s Thrush calls. If Vick was raised in Veery nesting habitat, how did he learn Bicknell’s Thrush vocalizations?

Photos and sonograms (frequency vs. time) of songs and calls for Bicknell’s Thrush, the hybrid thrush, and a Veery. Photographs kindly provided by: Kurt Hasselman (www.flickr.com/dah_professor) Veery and Jeff Nadler (www.jnphoto.net) Bicknell’s Thrush. Click on the graphic to enlarge it. Listen too all the calls and songs below.

It turns out that song learning is mediated and constrained by inherited sensory templates – neural filters that pass only particular sounds onward. In a world with many sounds, this makes sense; a young bird has to select appropriate song models rather than just any sound, bird song or otherwise, in the surrounding environment. It may be that Vick had the innate ability to vocalize some Bicknell’s Thrush sounds, like the call or part of the song, but that he learned the complete Veery song from those around him.

We don’t know how often these woodland thrushes hybridize. Because Catharus species look so much alike, perhaps we are simply unable to detect them, and we just happened to be the right people in the right place this time. As more and more studies are conducted on Bicknell’s Thrush, due to its high conservation priority, we’ll certainly learn more. Recently, some of our colleagues reported a case of Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s thrushes hybridizing in the northernmost part of Bicknell’s breeding range. How often this happens and what mechanisms facilitate a breakdown of the species boundary are fascinating topics for future study and monitoring.

For example, global climate change has been suggested to drive hybridization between closely related species, and has been identified as an imminent threat to the coniferous montane forests in which Bicknell’s Thrush breed. As its breeding habitat and current range of Bicknell’s Thrush contract via predicted upslope migration of the Balsam Fir climatic envelope, pushed by upslope migration of northern hardwoods forests, contacts between Bicknell’s Thrush and Veery would be predicted to increase. Results of recent 17-year survey of breeding songbirds across an elevational gradient in the White Mountains of New Hampshire by our colleague Bill DeLuca conform to this prediction. The upper elevational boundary of 9 of 16 low-elevation species shifted upslope by an average of 325 feet, while 9 of 11 high-elevation species shifted downslope an average of about 60 feet, possibly from changes in forest composition from acid precipitation. The likelihood of hybridization between Bicknell’s Thrush and Veery may very well increase over time. And with any luck, ornithologists and Mountain Birdwatch volunteers will still be out there on the trails tracking populations of these remarkable songbirds.

Learn and Explore More

- Explore photographs and listen to recordings of the hybrid thrush at Cornell Lab of Ornithology Macaulay Library.

- Read the abstract of the published paper at the Wilson Journal of Ornithology or request a PDF from the author.

- Learn more about Mountain Birdwatch and other mountain songbird research and conservation at VCE.

Listen to Songs and Calls of Bicknell’s Thrush, Veery, and the hybrid thrush

Bicknell’s Thrush Song:

Bicknell’s Thrush Calls:

Hybrid mixed Song:

Hybrid Veery Song:

Hybrid Calls:

Veery Song:

Veery Calls:

Wow, actually, double wow! Great discovery and well-done article! Congrats!

It was pretty cool to discover this and fun to write about!

This is really fascinating! Thank you for the work and the article, and the sounds.

Thank you. It was fun to put together! I am glad you enjoyed the story and the natural history.

Thank you for an amazing and extremely well written article, Kent!

Congratulations on an incredible find. I’m so glad you shared your exciting story with all of us. Next time I’m climbing a peak in the Adirondacks, you can be assured I’ll be listening!!

Thank you Ginny for the kind words. I just love these birds. They just keep on surprising us too! Enjoy spring migration!

Beyond a cool find and experience. Nice work.

Any sense that the BITH characteristics are stronger than the Weery? Or….?

We don’t really. Hard to say behaviorally, although he was in BITH habitat, so maybe that says something. He stuff around the area for about a month and then disappeared.

Isn’t the likelihood of a successful second generation pretty good?

“Not knowing when the dawn will come, I open every door.” Emily Dickenson

I really don’t know. Based on his efforts, I’d say yes. But I don’t know the status of his fertility. I assume there is quite a good chance.

This is an amazing story, Kent. In depth study and research is incredible beyond words. And the essay is well written with every detail with graphic taped songs to describe this discovery to tell all if us. We are all enriched by this study and are grateful to the whole team.

Thank you so much. It was a fun find for sure. I am glad you enjoyed the story about it.

What a great story of discovery!!! Perfect timing for Kent and colleagues be in the field and most importantly how it pays back the years of preparation for VCE staff like you, to know the habitat of both species, your ear training to id species and hybrids, be prepared to record nature sounds, to take blood samples and mist net the bird in few minutes and band “Vick”. Few field biologists are well prepared to do serendipitous discovers. Well done!

Thanks Eduardo. You are so nice to say that. See you in Ithaca soon!

We’re a little late catching up with this story, but wow! What an amazing find! Congrats!

Karen & Terry

Thanks! Hope you are well out there and not too hot yet! I don’t even want to know what your 2018 butterfly list is up to!

Hello, I am an oil painter and am interested in doing a painting from the first photo in this article. Can you tell me how to contact the photographer?

Jeff Nadler (www.jnphoto.net)