New birders might mistake a commonly-seen Red-bellied Woodpecker (pictured here) for the Red-headed Woodpecker, which is rare in Vermont. The eBird filter will account for that. Photo credit: Craig K. Hunt

In the age of Big Data, eBird provides a massive wealth of information: it recently surpassed 2 billion global bird observations, and eBird Vermont, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life, alone contains more than 800,000 checklists from over 18,000 observers, totalling 8.7 million bird sightings.

These data are used to make species distribution models and track change in populations and migration timing. So it’s important for records to accurately show when and where birds occur.

For the most part, birding is built on trust. No one will doubt a report of a Northern Cardinal at a bird feeder. But unexpected records require closer scrutiny.

Unlike iNaturalist, where photos or audio are required to reach “Research Grade” validation, eBird does not require physical evidence of most sightings. So how do we know that people saw what they say they saw?

That’s where the eBird review process comes in.

Let’s say you spot a surprising bird. You open the eBird app to report it, only to find the species doesn’t appear on the default list. You expand your search and enter it, but the app prompts you to provide comments before submitting.

Congratulations on finding a rare bird and encountering the eBird filter! Your sighting will be reviewed by a small but dedicated team of volunteers before it’s included in the eBird dataset. This step ensures that eBird Vermont provides valuable, reliable, and accurate information to both enthusiastic bird chasers and research scientists.

What is a “rare” bird?

When creating a checklist in the eBird app, you may notice symbols next to species names, which indicate how common that species is at your area and time window (a three-week period centered on the current week, and a location starting at a 20 by 20-kilometer square and larger if checklist coverage is low).

No marker (Common): Reported on 6% or more of checklists at this location and time period.

![]() Orange half-circle (Infrequent): Reported on at least one, but fewer than 6%, of checklists.

Orange half-circle (Infrequent): Reported on at least one, but fewer than 6%, of checklists.

![]() Red dot (Unreported): Not reported on any checklists in that time period and location. Note: Merlin calls this category “rare,” though it’s not flagged by eBird.

Red dot (Unreported): Not reported on any checklists in that time period and location. Note: Merlin calls this category “rare,” though it’s not flagged by eBird.

![]() Orange R (Rare) : Flagged by the filter. Flagged species require supporting comments before submission.

Orange R (Rare) : Flagged by the filter. Flagged species require supporting comments before submission.

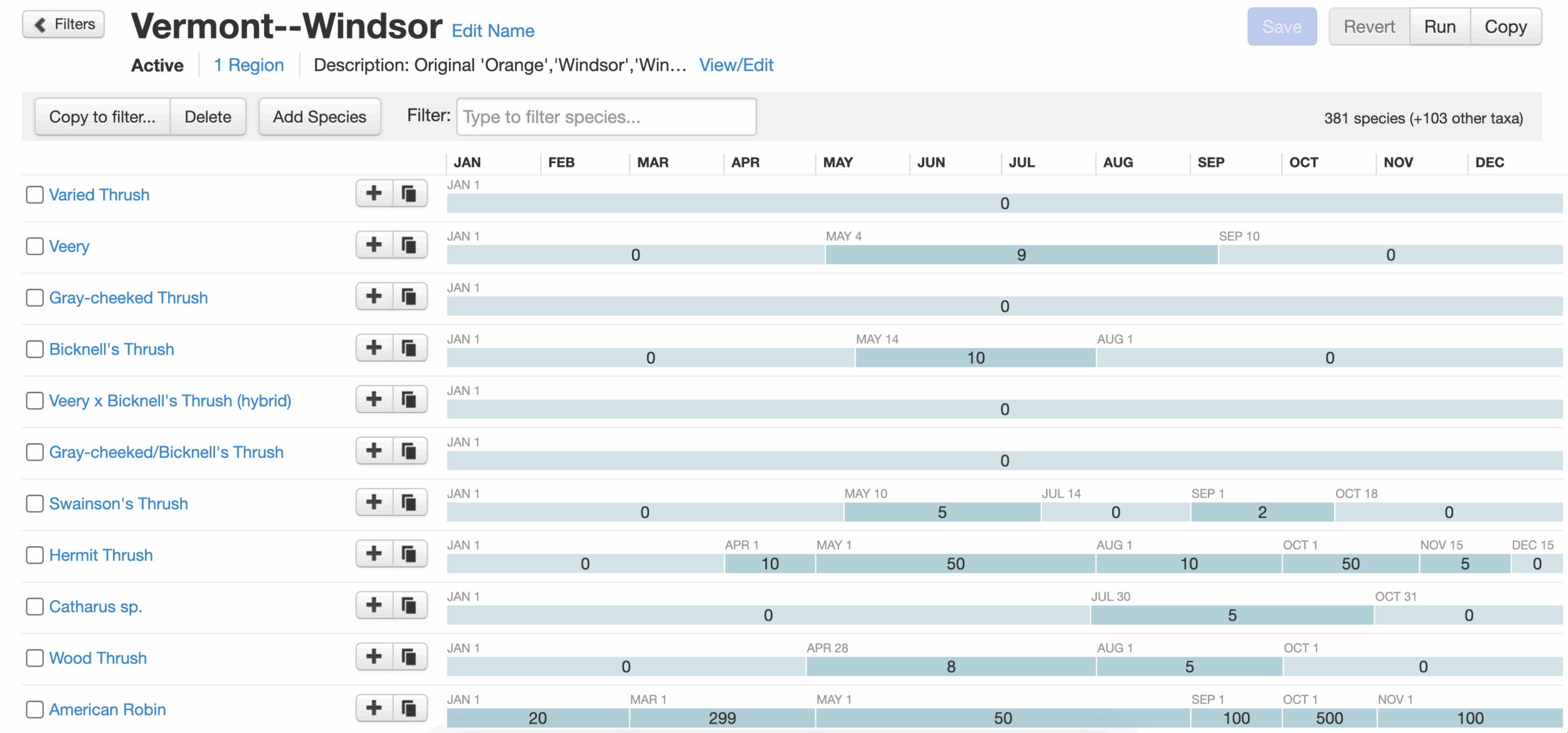

Which species are flagged as rare is controlled by the regional filter, a spreadsheet curated by reviewers based on past data and their experience. Filters are set for each county or multi-county region and contain the maximum expected count for each species and date. If your count on a checklist exceeds that threshold, the record is flagged.

This filter excerpt from Windsor County shows expected checklist maximums for thrushes by date. Exceeding these triggers a flag.

This filter excerpt from Windsor County shows expected checklist maximums for thrushes by date. Exceeding these triggers a flag.

Species will be flagged by the filter for three possible reasons:

- Rarity: Unusual in the region (count is always zero, or doesn’t appear on the filter at all). For example, as a western bird with only a few vagrant records in Vermont, Varied Thrush will always be flagged.

- Out of season: Not unusual in the region, but reported outside of its normal date range (set to zero in current time period, but present in other times). This could be a Bicknell’s Thrush in Vermont during winter, when they should all be in the Caribbean!

- High count: An unexpectedly high number of individuals. For example, a checklist with more than nine Veeries during the breeding season. This should prompt you to be specific about how you counted individuals: was it an exact count of unique individuals? An approximate count by tens? A rough estimate of a distant flock?

Filters are sometimes altered during events like the Great Backyard Bird Count or Christmas Bird Count to account for new birders. For example, filters might be tightened for the Red-headed Woodpecker (uncommon, somewhat shy feeder visitor) because many newbies will report it when they meant the more common Red-bellied Woodpecker.

What happens next?

Once submitted, flagged records go into the review queue of your local reviewer, a volunteer with expert knowledge of the local area. Reviewers are listed on the eBird Vermont partners page.

Some records are immediately confirmed without the need for additional detail, using:

- Documentation: Detailed descriptions, photos, or audio.

- Reliability of the eBirder: Observer is personally known to reviewers as someone who routinely provides responses and adequately documents birds. The Cornell reviewer handbook notes that these known eBirders “can reasonably be held to a lower standard for low level rarities or birds known to be present.” (Note that who gets to be held to a lower standard can sometimes be a point of contention.)

- Not truly rare: The filters can be coarse and cast a wide net, catching some records that don’t need to be flagged. According to VCE co-founder Kent McFarland, eBird Vermont hopes to someday transition to a more complex filter system. For example, high-elevation species like Bicknell’s Thrush could be allowed at high elevations but flagged at nearby low-elevation sites within the same county.

- A known bird: Long-staying rare birds that have been observed by many people or breeders at known sites require less documentation after their initial discovery.

Other records will be unconfirmed because they do not meet the standards for documentation and will not appear in eBird’s public data output. They won’t be shown when users search for the species using the Explore function, nor will they appear on a region’s recent sightings page. However, they will always remain accessible to the user who submitted them.

A record may be unconfirmed because of:

- Inadequate documentation: This can be overridden at a later date if better documentation is received, such as a longer description or adding photos.

- Clear misidentification : In rare cases, the reviewer feels certain that the documentation indicates a different species than what was submitted. For example, a “Red-headed Woodpecker” described with red on the crown and a barred back .

- Rejection by the Vermont Bird Records Committee: The VBRC maintains the official state checklist. In eBird Vermont, we follow VBRC rulings. It is unlikely but possible that a record would initially be confirmed by an eBird reviewer but later rejected by the VBRC.

- Other checklist effort issues: Imprecise locations or too-long distances.

If your record is lacking in documentation, you’ll receive an email from your reviewer that will read like this:

“Thank you for being a part of eBird. To help make sure that eBird can be used for scientific research and conservation, volunteers like me follow up on unusual sightings as a part of the eBird data quality process.”

This template email is a request to clarify with information that will determine if your record is confirmed or left out of the public data output. If you don’t respond within 14 days, your submission will automatically be unconfirmed unless the reviewer reaches out again. Remember, unconfirmed just means it’s not public—your personal lists remain the same!

Plus, if you can see the reviewer’s point—you actually did see a Red-bellied Woodpecker—you can change or delete your observation at any time. Changing your observation after a reviewer has contacted you will push it back into the review queue.

What happens if a reviewer makes a mistake?

Like all community science data collection, eBird isn’t perfect. While filters and reviewers catch most issues, some errors can slip through unnoticed. Fortunately, because eBird amasses billions of records, a small number of outliers is unlikely to affect model quality. When modeling such massive amounts of data, researchers have even figured out how to calibrate to the differences in skill among observers.

There are two types of errors in eBird data that could result from an incorrect judgment in the review process. Even if they don’t cause problems in data analysis, they present challenges for birders:

False positive: Approved report of a species that wasn’t present. A birder reports an early Eastern Wood-Pewee in the last week of March, when it was really just a European Starling mimicking the pewee. The reviewer hears the observer’s short audio clip that does sound like a pewee and approves it. Birders might chase nonexistent rarities and trust in eBird might decline. But birders are used to using their judgment and trust, because sightings go out to eBird rare bird alerts prior to assessment by reviewers anyway.

False negative: Rejection or failure to confirm a report of a species that was really there. A birder does truly see an early Eastern Wood-Pewee in March, but their documentation or description (merely writing “I know what I saw!”) was not compelling enough for the (reasonably!) skeptical reviewer to approve the record.

Birders might miss the opportunity to observe a legitimately rare bird. And for the observer, this doesn’t feel good! There’s a risk the observer may feel devalued and stop submitting records to eBird. But you can avoid this frustration with a few extra steps.

How can I make sure my reports get confirmed?

- “Take your time and fill out the comments,” says Kent McFarland, VCE Conservation Biologist and statewide eBird reviewer. “Don’t be lazy—a volunteer won’t have to bother you if you make it easy for them!”

- If you have photos or audio, attach them as soon as you are able.

- Write a good description. “Identified by Merlin” or “Just like the field guide” are not sufficient to convince a skeptical reviewer! With the proliferation of smartphones with decent cameras and audio recorders built in, writing good descriptions has become somewhat of a lost art among birders. This 20 year old guide provides excellent examples of slam-dunk descriptions of rare birds.

- Know when to leave a bird unidentified. In eBird, you can submit birds not identified to the species level as a “spuh” (Empidonax sp.) or “slash” (heard-only Golden-winged/Blue-Winged Warbler).

- Be honest when you are uncertain. Don’t be afraid to reach out for advice from other birders or social media groups for help.

No matter what the final decision, your record will still count for your personal lists! Unconfirmed records are still visible to you in your life list, My eBird, and remain in all your personal data downloads.

Conclusion

Be patient with your reviewer. You’re both on the same side: trying to be certain you contribute accurate observations, so all birders can enjoy birding.

And here’s a tip from me: Many vagrants occur in late summer and early fall as young birds are dispersing. So go out and find some rare birds!

Read more

YouTube: “How eBird Review Works” by Doug Hitchcox

“A Lost Art?: Writing Descriptions of Rare Birds” by Dave Irons

“eBird Vermont Welcomes Five New Data Reviewers”