Legal Lead Fishing Gear Is Still Killing Loons

A dead loon is readied for a necropsy to determine the cause of death. Photo credit: Isabella Soddu

Saturday, July 19th was LoonCount day, a statewide event dedicated to the monitoring of Vermont’s Common Loon population across 160 lakes. As the interdisciplinary interns, Sammi Rizzo and I were tasked to check on some high-priority lakes that hadn’t been adopted by volunteers. We strapped our kayaks onto the field vehicle and drove to the Northeast Kingdom to make our first stop of the day: Spectacle Pond.

Our survey began as usual. Sammi and I paddled along the shoreline and peered into any reeds or pockets of vegetation that might be hiding the signature indentation of a loon nest. We had just started our search when I heard Sammi call to me up ahead. There was an adult loon bobbing next to the shoreline, its head bent deeply and unnaturally into the dark water. It was dead.

We contacted VCE loon biologists Eric Hanson and Eloise Girard, who told us to collect the loon and put it in a freezer ASAP so a necropsy could be performed to parse out the cause of death.

We tracked down a confused park worker for some garbage bags and did our best to collect the bird. The process was smelly, soggy, and emotionally heavy. I love loons, and seeing one up close was an experience I never thought I’d have. The details of its patterning and the slightly green iridescence of its head made me catch a breath. At the same time, it felt indescribably wrong to touch something so sacred and shovel it into a plastic garbage bag.

Windows down, we listened to crackling banjo music in silence as we drove to the Vermont Institute of Natural Science (VINS) to drop off the bird. The highway air ripped through us as we tried to ignore the smell of decay in the trunk.

Loon necropsies were coincidentally scheduled for the following Wednesday, and Sammi and I arrived at VINS in the morning to help out. Three tables lined in plastic were set out for three necropsies. Our bird wasn’t included in that day’s lineup, but a loon Eric Hanson had found dead on the very same pond two months prior was.

Loon Biologist Eloise Girard (right) speaks with Danielle Scott (left), a veterinary student while two children look on. Photo credit: Isabella Soddu

We made our way around each of the tables, watching three loons simultaneously get peeled open layer by layer. Each bird was in various stages of decay and had come from different lakes in and around Vermont. We found lead jigs within the gizzards of all three loons.

I watched Mark Pokras, a seasoned veterinarian from Tufts University, pull one out like a little silver dollar from a very green and gritty treasure chest. “If you can scrape the top layer, it’s probably lead,” he explained, as he used a scalpel to shave off a tiny piece of the top of the jig. The interior shone silver.

State laws have regulated the use of lead tackle since 2007. Since then, lead sinkers of 0.5 ounces or less have been illegal to use or sell in the state of Vermont. As a direct result of the ban, lead-related loon deaths in Vermont have decreased significantly. But for some unknown reason, rates of lead poisoning have begun to trickle back up in recent years. Currently, 20% of all adult loon deaths are attributed to lead poisoning. Twelve loons died from lead poisoning between 2019 and 2023 in Vermont.

Out of the three loon necropsies, all three retrieved lead jigs are currently legal to use in the state of Vermont.

The contents of a loon’s gizzard: small stones, fishing line, and a piece of lead that lead to its death. Photo credit: Isabella Soddu

Loons pick up lead fishing gear by snagging live bait from angler’s fishing lines, or by swallowing dropped lures at the bottom of the lake floor. Like many other species of bird, loons swallow small rocks to store within their gizzard, a bird-specific organ designed for digestion. In the gizzard, a combination of strong acid, a rough internal layer, and the grinding of the rocks allows loons to digest difficult material. But if a loon eats a fish tangled in lead fishing gear, or mistakes a lead sinker as a pebble at the bottom of the lake floor, it will begin to wear away in the gizzard while lead slowly seeps into the bird’s bloodstream. According to Dr. Pokras, it’s a guaranteed death sentence, one that’s nearly impossible to remedy once the lead has been swallowed.

One of the necropsied loons from Maidstone Lake was an exceptionally large, seemingly healthy adult male. Dr. Pokras showed us the thick, pink layers of fat surrounding its sternum, clear evidence the bird had been eating well. When Dr. Pokras fully opened the body, he found a puncture wound that pierced through the liver. The likely story? Lead poisoning had weakened the loon, making it vulnerable to attack by a healthier rival. Another loon delivered a sharp, fatal blow before the lead poisoning could kill the bird. As Dr. Pokras noted, one of the tragedies of lead poisoning is that its brutality is non-exclusive: even the healthiest individuals in a population aren’t immune.

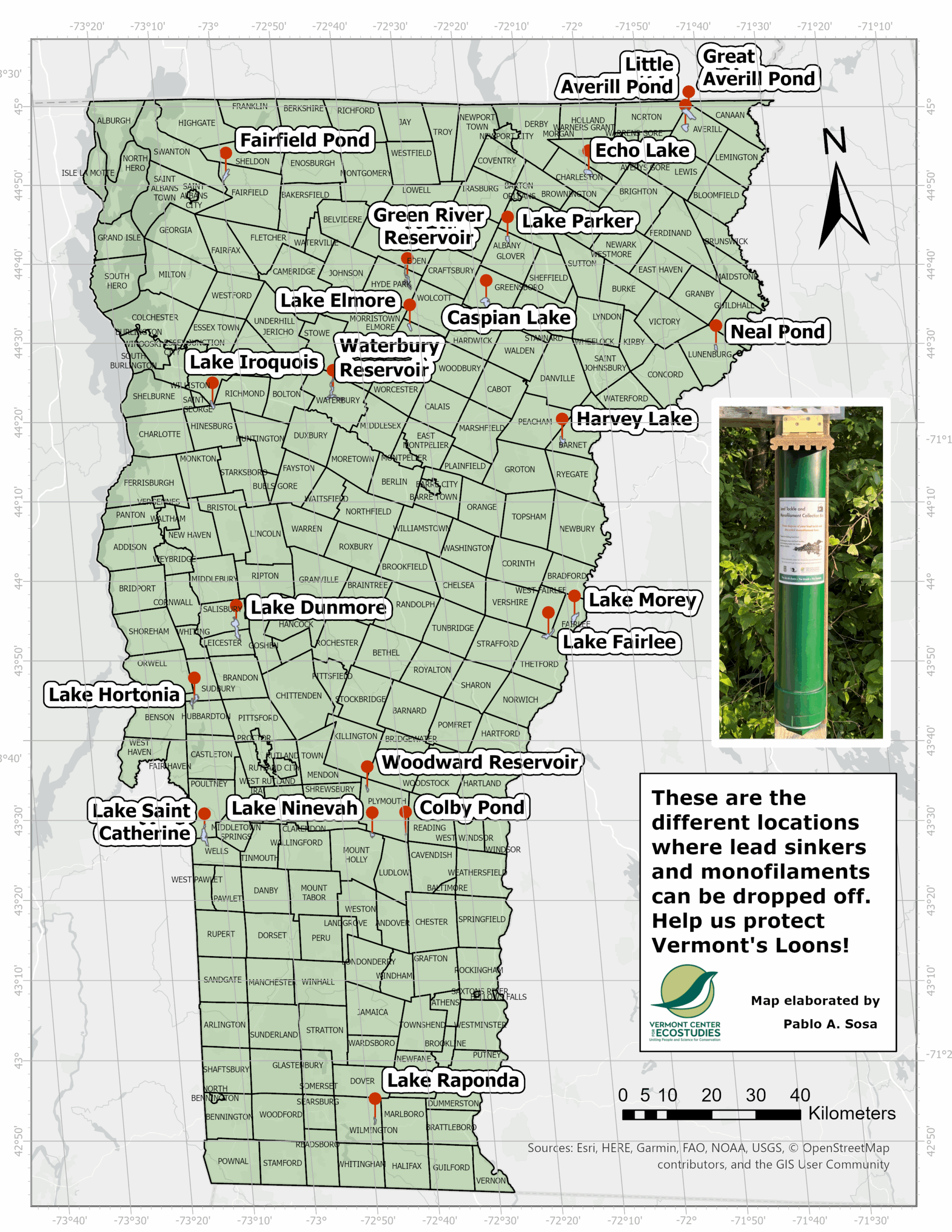

In hopes of preventing tragic incidents such as these, VCE is currently partnered with Vermont Fish and Wildlife to lead the Fish Lead-Free Project. The goal is to spread awareness and help anglers switch their lead tackle to safer options. Across the state, collection tubes have been added to the boat access at lakes and ponds where lead jigs and sinkers, as well as other fishing gear, can be discarded safely. As for alternatives, Fish Lead-Free recommends switching to non-toxic tackle made from tin, bismuth, steel alloy, or tungsten.

Seeing the lead tackle being removed from each one of those gizzards made it clear to me that regulation doesn’t always mean resolution, and change is still deeply necessary. It turns out that the loon Sammi and I found on Spectacle Pond likely suffered trauma from another loon, and there were signs of an infection that could have made it weak and prone to an attack. But three loons dead from lead is plenty enough to show a pattern. These deaths aren’t anomalies, but rather a long-standing trend that continues to threaten Common Loon population across Vermont and the Northeast United States.

The good news is that unlike the many other ecological challenges these birds face, the solution isn’t complicated. It is just a switch that’s overdue.

If you know someone who uses lead fishing gear, encourage them to switch to lead-free alternatives made from non-toxic materials such as tin, bismuth, steel, tungsten, and ceramic. Find a list of non-lead tackle manufacturers and retailers on fishleadfree.org/vt. Find a collection tube where you can safely dispose of your lead tackle in the map below.

Were any of the loons in this story actually tested for lead poisoning? Were any of the pieces of tackle actually tested for lead? Non-lead jigs are similar in appearance and density to lead.

Hi Noel, This is VCE’s loon biologist Eric Hanson. When Alden forwarded your note, I at first did not think we did test the jigs for lead, but I was thinking of a previous necropsy session where we did not have the test kits. We did test and these were positive for lead.

Hi Noel, as you point out, there are several great replacements for lead fishing gear, such as tin, bismuth, steel, tungsten, and ceramic, and the price difference is minimal. All the more reason to make the switch!

Please update the VT map to include Shadow Lake, Glover, where a collection tube is located at the DFW access to safely dispose of lead tackle and fishing line. Thank you.