A banded adult Northern Saw-whet Owl takes flight after its release on the Mt. Mansfield ridgeline, 1 August 2018. Photo courtesy of Mike Sargent.

VCE’s field crew ascended to the Mansfield ridgeline on 31 July for a final summer banding session, thankful that a threatening forecast never materialized. Very warm temperatures, light winds and mostly clear skies made for a quintessential summer evening. Birds, however, were extremely quiet, and captures surprisingly low, as last week. Despite setting up more nets than usual (27), we captured only 5 individuals by nightfall. Even reliable dusk vocalizers like robins, Bicknell’s Thrushes, and White-throated Sparrows were virtually silent. Consolation came easily, however, via spectacular planetary viewing through a spotting scope, with Venus, Jupiter, Saturn and Mars all drawing rave reviews.

Forgetting how much shorter daylength has become since the June solstice, we were back on the ridgeline well before 4:30 am to open nets. Clouds had moved across the sky, and we waited a good 30 minutes for dawn to break. As it turns out, losing that extra bit of sleep was a worthwhile sacrifice, as our first net check produced a much-anticipated Northern Saw-whet Owl, a bird I had rashly predicted (and even tried to lure in with post-dusk playback) for the past two weeks. All present were thrilled, and everyone was able to enjoy a handheld encounter with the diminutive, remarkably placid bird. We seldom capture this nocturnal predator on Mansfield (understandably, as we don’t run nets at night), but Northern Saw-whets are probably more common than any of us suspect, especially in years like this following bountiful cone crops, when rodent prey (e.g., red-backed voles) are more abundant.

A crowd-pleasing adult Northern Saw-whet Owl poses after being banded on Mt. Mansfield, 1 August 2018. Photo courtesy of Mike Sargent.

The remainder of Wednesday morning yielded surprisingly little action, either in or outside of our nets. We ended up with a 2-day total of only 24 captures (compared to 62 on 26-27 June, 53 on 10-11 July, 46 on 18-19 July). Especially perplexing was the scarcity of young-of-the-year birds — only 11, of which 5 were non-local Black-throated Blue and Green warblers. Unless the current Mansfield breeding season was a bust, with widespread nest failures, it is difficult to explain the near-absence of free-flying juveniles of common montane forest species in our nets — we didn’t capture a single hatching-year Blackpoll or Yellow-rumped warbler, Dark-eyed Junco, or White-throated Sparrow! Our season-long observations indicated that red squirrels were almost non-existent on the ridgeline (despite the immense 2017 cone crop), so nesting productivity should have been high. Conditions until recently have been abnormally dry, and we did not sample insects or other arthropods, but it seems unlikely that food supply per se limited breeding success. There were no catastrophic weather events, so weather-related nest failures also seem unlikely. It could simply be that our limited netting (one day per week) doesn’t provide a representative sample of the birds present in any given week. It will be interesting to return in mid-September and see who is still on the ridgeline — though of course we’ll also catch passage migrants then — and to learn what fall banding operations like Manomet in coastal MA experience for captures of montane species like Blackpolls and Yellow-rumps.

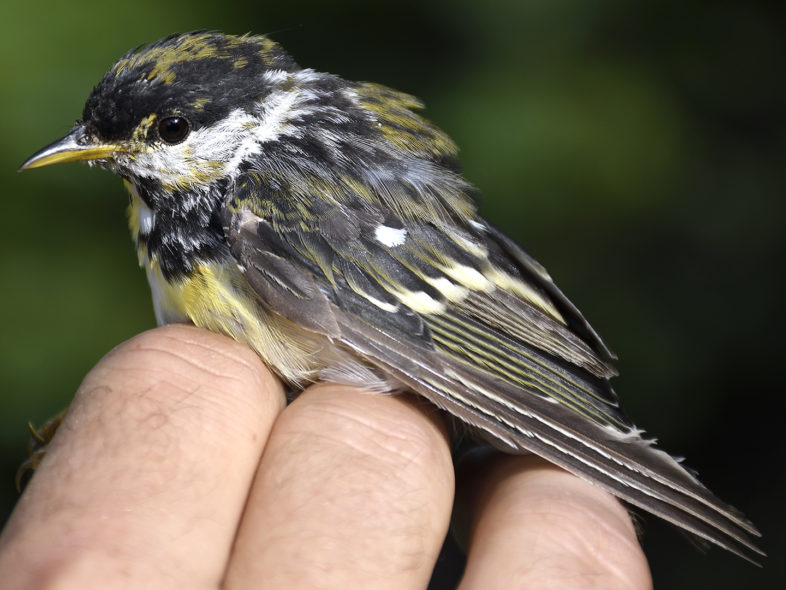

Nearly every adult passerine we captured was well into its flight feather molt, which may explain lower captures of that age class, as heavily molting birds are not inclined to fly much. One male Blackpoll Warbler was almost startling in appearance, literally intermediate between its breeding and winter plumages. A male Bicknell’s Thrush, first banded in July of 2013 and captured twice already this season, was likely incapable of any sustained flight. These two birds signal the seasonal transition that is just beginning, as long-distance migrants undergo their all-important annual molt. This process, which replaces worn feathers with a new and more robust set, is crucial for the impending fall migration. Molt, especially of flight feathers, is energetically costly, so most songbirds sandwich it between the end of nesting and the beginning of migration.

Bicknell’s Thrush #1931-76709, a 7+ year-old male first banded on 10 July 2013, in heavy post-breeding flight feather molt. This bird is beginning preparations for its fall migration and the impending winter season on one of four islands in the Caribbean Greater Antilles. Photo courtesy of Mike Sargent.

This individual thrush (and many others on the mountain) has only been back from its Caribbean winter quarters for 2+ months, yet it is already preparing for the return trip! I couldn’t help being struck by this realization, and that VCE will again follow the species down there, as we have since 1994. I fully expect we’ll be back in the Sierra Maestra of southeastern Cuba for a third consecutive winter, as we seek to determine the species’ overwinter distribution, abundance and habitat use on the island. For anyone interested, VCE’s good friend (and professional videographer) Michael Sacca has put together a nice piece from my iPhone video clips in Cuba’s Pico Turquino National Park this past January-February. You can view it below.

Returning the focus to Mansfield, our two-day banding total of 24 birds (17 on 24-25 July) included:

Northern Saw-whet Owl — new adult, probable male (small body size, wing length)

Bicknell’s Thrush — 5 (4 new juveniles, retrap of a heavily-molting male originally banded in 2013)

Swainson’s Thrush — 2 new adults (male in early primary molt, female in heavy flight feather molt)

American Robin — 2 (new adult male and free-flying juvenile)

American Redstart — 1 new hatching-year male

Blackpoll Warbler — 4 (3 new adults [1 male, 2 females]; 1 within-retrap female, all in heavy molt

Black-throated Blue Warbler — 2 hatching-year females

Black-throated Green Warbler — 4 (1 adult male in early primary molt, 3 hatching-year birds)

Yellow-rumped Warbler (Myrtle) — 1 new SY female, not yet molting

White-throated Sparrow — 2 adults (new male in early primary molt, within-season retrap female)

An adult male Blackpoll Warbler in transition between its breeding and non-breeding plumages. Photo courtesy of Mike Sargent.

This session concluded our 2018 breeding season field work on Mansfield. Despite the past two weeks’ low success rate, we had an excellent season overall, with > 800 mist net captures. VCE will return for a wrap-up outing in mid-September, both to find out which breeders are still present and to intercept some migrants. That annual trip rarely fails to produce a surprise or two, so stay tuned.

VCE Alexander Dickey Conservation Intern Tara Rodkey aglow with a banded Northern Saw-whet Owl, for which she waited patiently during VCE’s final three summer 2018 banding sessions on Mt. Mansfield.