Highly sweetened hot coffee and soda crackers fueled the daily pre-dawn departure of VCE-BIOECO’s field team into the chilly, damp air of El Todo. January 2020. © C. Rimmer

El Toldo, Cuba: 28 January, 2:50 am. Five of us—Cuban biologists Freddy Santana and Alan Mendez, field technician Yunier Caignet (aka Fis), our park guide Camelo, and I—guzzle highly sweetened coffee, bolt a few soda crackers, and shoulder day packs in the chilly, damp air. We set off in a silent procession under fiercely starry skies, headlamps our only illumination, plodding boot steps and “tinking” tree frogs the only sounds. We need to cover 12 kilometers before dawn, the witching hour of Bicknell’s Thrush.

Day three of our weeklong field survey of El Toldo, a wilderness high-elevation plateau deep inside eastern Cuba’s 71,000-hectare Alejandro de Humboldt National Park, is underway. Today’s target is Pico Toldo, the Park’s highest summit at nearly 1,200 m. Camelo doubts we’ll find a navigable trail up the peak’s steep slopes of dense “cloud charrascal” forest. Undaunted (we’re armed with machetes, after all), we hike on. Conversation is scant, but hopes high for our first encounter with Bicknell’s Thrush (BITH). After two days of unrewarded surveys in patches of broadleaf “pluvisilva” forest embedded within El Toldo’s boundless Cuban pines, we’re optimistic our luck will turn.

Alan Mendez in a patch of dense, wet pluvisilva forest on the El Toldo plateau of Parque Nacional Humboldt. Despite the habitat’s seeming (to us ornithologists) suitability for Bicknell’s Thrush, the VCE-BIOECO team turned up nary a bird during a week of intensive surveying, January 2020. © C. Rimmer.

If VCE has learned anything in 28 years of studying BITH, it’s to forego expectations. We think we have our quarry figured out, and, suddenly, we don’t. I was back in Cuba for a fourth consecutive winter because the species had thrown us a curveball the previous February. Following our unforgettable expedition to the remote cloud forests of Sierra Maestra’s Bayamesa National Park, which yielded several thrushes, we had surveyed an expanse of high-elevation broadleaf-pine forest in central Humboldt. Descending from the highlands, no BITH under our belt, we were shocked to stumble on a vocalizing bird in disturbed, secondary forest at 650 m elevation, near the tiny hamlet of Riito. We netted and banded the bird—a yearling. Was this an outlier, a naïve youngster, perhaps unable to secure a territory in prime habitat, who had settled for the best he or she could find? The plot thickened when, two weeks later, my Cuban colleagues returned to confirm this bird’s continued presence, then found three additional thrushes nearby!

Our thinking about BITH distribution and habitat selection in Cuba had been turned on its head, necessitating a 2020 follow-up field trip. We needed to not only carefully investigate the situation at Riito, but more exhaustively survey an array of “non-traditional” habitats. So it was that now, in late January, while my team scoured pluvisilva and charrascal forests on the El Toldo plateau, Cuban colleague Nicasio Viña was leading a team back in Riito. We would soon learn that four days of concerted point counts and playbacks there revealed no BITH anywhere! How to explain this absence, after the presence of four birds in 2019? We’ll never know for sure, but we can surmise that these may have been young, inexperienced birds, who adopted a “floater” strategy, moving constantly through suboptimal habitat or inhabiting patches only temporarily. This is well-documented in other migrant songbirds that, like BITH, occupy discrete winter territories. Not everyone secures a piece of prime real estate.

Bicknell’s Thrushes may have been absent, but the ethereal songs of Cuban Solitaires were rarely our of earshot in El Toldo. © Nicasio Viña

Back to El Toldo, 5:50 am: exactly three hours after our coffee-fueled departure from camp, the first glimmer of dawn appears. Twenty minutes later, we arrive at the base of Pico Toldo, headlamps no longer needed. As feared, no trail ascends the impenetrable bamboo charrascal understory to the summit, so Camelo and Fis gamely set off with machetes to create one. At 6:20, Freddy, Alan and I begin point counts along the old mining road we’ve just hiked. Habitat looks promising, as it has elsewhere in El Toldo, but BITH are nowhere to be found. Three signature endemics dominate the airwaves, providing ample consolation: Cuban Trogons, Cuban Todies, and (my personal favorite) Cuban Solitaires. Trail cutting proves too arduous a task for Camelo and Fis, so we manage to haul ourselves only halfway up Pico Toldo. No thrushes there either.

The view midway up Pico Toldo (left), where senior citizen Rimmer (right), bushed after a 12-km pre-dawn hike, conducts a rare sitting point count. © C. Rimmer (right), A. Mendez (left)

Over the next four days, we learn a great deal about where BITH are not, which is anywhere on the El Toldo plateau, or, apparently, inside Humboldt National Park. We cover >100 km on foot and conduct close to 90 point counts. We hear more Cuban Solitaires than seems humanly possible—their haunting, dissonant song never fails to spark wonder in me. And, we revel in the landscape’s remoteness (I didn’t hear a jet overhead for the first four days). Our team is lively, fun-loving and patient (especially with my imperfect Spanish…). Our tent camp on the banks of the soothing and literally drinkable Rio Piloto is a perfect base for the week. Afternoon swims become a daily ritual, and we are fed like royalty by Yani and Uincho, who concoct hearty lunches and dinners (staples being rice, beans, ñame, and…canned meat) on the open flame.

The VCE-BIOECO team’s communal dining space (left) and kitchen (right, with cook Yani and her helper Uincho) on the banks of Rio Piloto in El Toldo. We ate like royalty. © C. Rimmer,

We backpack out of the park, reunite with Nicasio’s team, and move 250 km west to wet lowland karst forest in Carso de Baire. This coffee-growing region, just north of eastern Sierra Maestra, features a distinctive landscape of mogotes—dramatic, domed limestone tableaus with sheer, densely forested walls and tops—surrounded by shade coffee and other other small-scale agriculture. Having found BITH in and around similar mogotes along the northern Dominican coast, we’re disappointed that point counts here also come up empty for BITH. However, we are deeply touched by the welcoming, gracious local residents, who consistently invite us—a scruffy gang of binocular-toting strangers—into their homes for coffee and meals.

Not your typical coffee bar: a gracious and welcoming Cuban homeowner makes coffee in her rustic kitchen for the VCE-BIOECO field team, 3 February 2020. © C. Rimmer

With our time winding down, and needing to encounter at least one BITH in 2020, we end our expedition at Pico Botella, Sierra Maestra’s only road-accessible tract of cloud forest. There, as in 2017, we find a handful of our nemesis, managing to net and band two birds. My Cuban colleagues are delighted, while my feelings verge more on relief! We discuss possibilities of launching more intensive future studies here, investigating the ecology and demography of BITH, perhaps the entire cloud forest bird community as well. I’m more than a little interested.

A wet and bedraggled biologist with a hard-earned Bicknell’s Thrush banded at Pico Botella in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra, 8 February 2020. © Leydis Zaldivar

After these three weeks, and, in fact, the past four winters, we are left with an inescapable but unsurprising conclusion: BITH is a cloud forest specialist on Cuba. We’re somewhat disappointed, having hoped to discover populations overwintering in other habitats. Cuba is remarkably well-conserved overall, a far cry from occupied habitats in the species’ core winter range on Hispaniola. However, our Cuban findings are vitally important, as they reaffirm the strategic need to continue focusing conservation efforts in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Without doubt, Cuba provides critical and secure refuge for BITH, even if it doesn’t harbor a mother lode. Moreover, our colleagues there are deeply committed to continued collaboration as we together study and conserve this globally vulnerable species. I suspect VCE has additional pages to turn on this enchanting island.

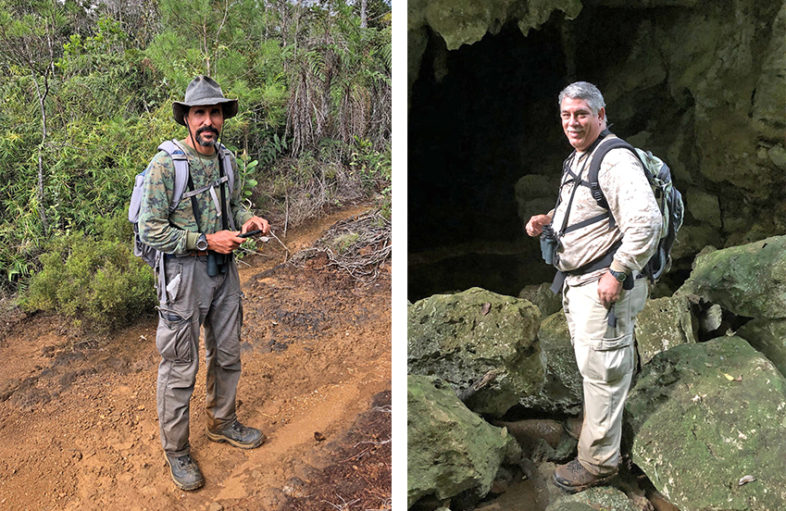

Two of VCE’s outstanding Cuban colleagues in action during January 2020: Freddy Santana of BIOECO (left) pauses during a long day of field surveys in El Toldo, while Nicasio Viña mugs for the camera in wet limestone forests of Carso de Baire. Neither area yielded Bicknell’s Thrush during VCE’s field surveys, but other rewards were bountiful. © C. Rimmer

Nice read Chris.

I admire and salute all the intensity and tenacity in your quest for the discreet Bicknell’s Thrush in Cuba. My experience and past expeditions make me share with you your disappointments and joys of discovery. The absence of thrushes is as significant as their presence, thus nourishing our conservation efforts. The work in Cuba requires very long and persistent efforts before even setting foot in the field. Congratulations Chris and the entire BIOECO team. Thank you for sharing your stories of expeditions.