Most of our knowledge regarding the migration timing of songbirds comes from birding observations made during the day, even though much of the actual migration occurs at night. Is this a problem? Can’t we just use birding observations to understand migration timing? Well, a new nocturnal migration study I’m involved with suggests… maybe not.

Global climate change is expected to advance the spring arrival of many migrant bird species, but documenting these changes requires knowledge of current migration phenology. Ornithologists often turn to community science birding data—like those reported to Vermont eBird and iNaturalist—to understand these patterns. Indeed, these data have been used to document advances in the timing of spring migration for many bird species in connection with anthropogenic climate change. These migrant populations are potentially vulnerable to ecological mismatches, where peak resource availability (e.g., insects) no longer matches the peak in arrival or breeding dates of these populations. Before we can detect advances in migration timing and assess the vulnerability of migrant populations to these mismatches, however, we must have good baseline estimates of arrival dates.

This goal may be especially challenging in species like Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum), that are relatively cryptic and non-vocal following spring arrival on the breeding grounds. But what if we could detect their arrival above the breeding grounds? This idea may sound like science fiction, but we’re learning that migration timing can be readily detected using bird’s nocturnal flight calls—the nighttime vocalizations made by migrants during flight. Many species make species-specific flight calls that sound quite different from their diurnal calls; improvements in artificial intelligence can automate the detection of these calls.

To bring all these ideas together, Joe Gyekis (Penn State, College of Health and Human Development), myself, and citizen scientist Bill Evans (nocturnal flight call guru) compared spring observations from nocturnal audio recordings to diurnal eBird observations in central Pennsylvania (Centre and Union Counties, April and May, 2008-2018). Homemade microphones were placed on rooftops in open buckets, which serves to garner faint sounds from the night sky. The entire set up is easy to replicate, in case you are interested, and can be constructed for <$100.

One of the bucket microphones used to record the nocturnal flight calls of migrating Grasshopper Sparrows / © Joe Gyekis

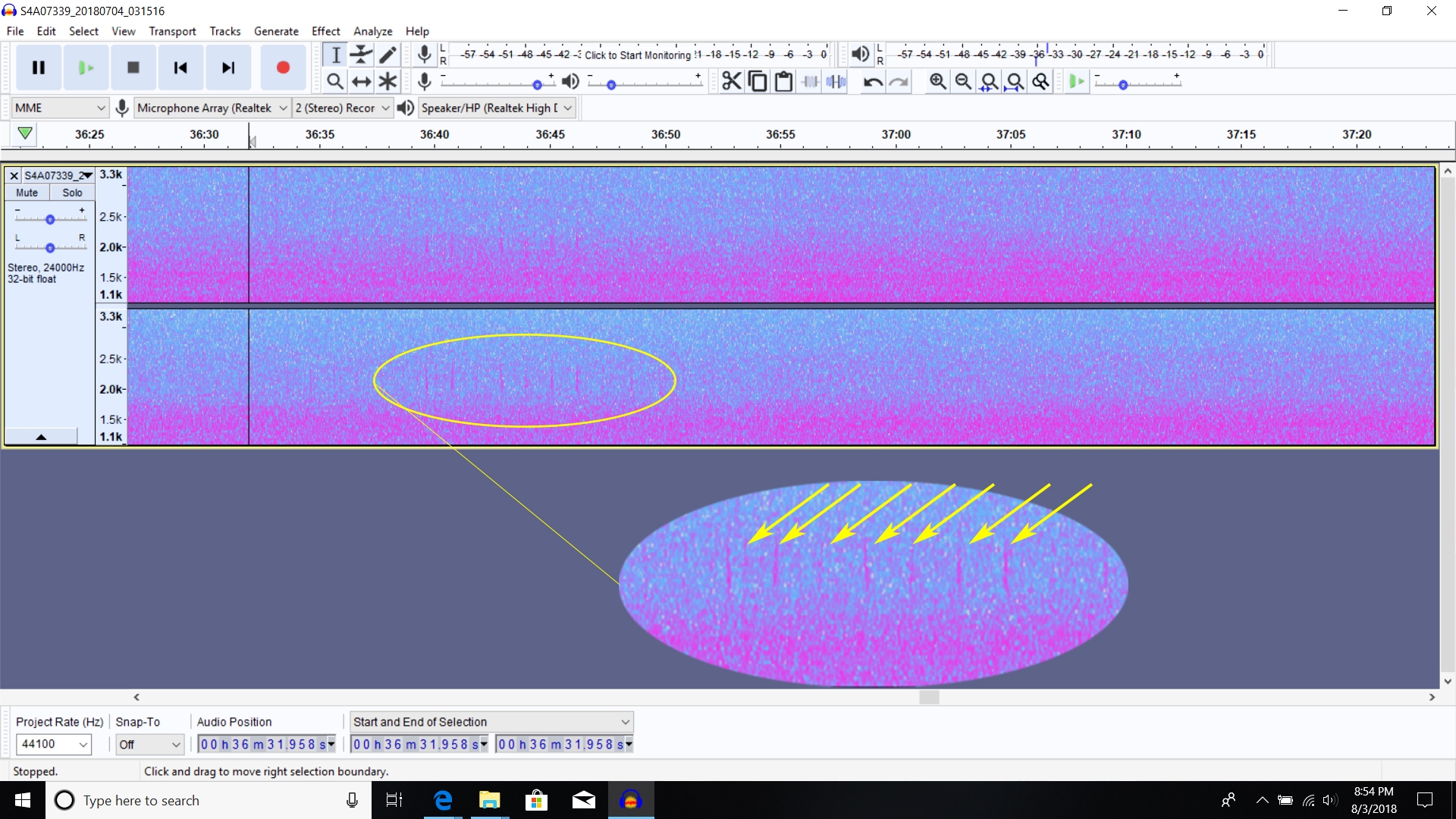

These bucket recording stations are only capable of recording vocalizations of birds passing directly over the roofs (i.e., as they depart around dusk or prepare to land around dawn). The bucket microphones recorded all night long through April and Mayof 2018, and Grasshopper Sparrow flight calls were automatically detected using OldBird Tseep-r freeware software. The nocturnal flight calls were also manually confirmed by Joe Gyekis, who conservatively denoted 79 different Grasshopper Sparrows from the recordings. For comparison, we downloaded >15,000 complete eBird checklists over the last decade for April and May from the same counties of Pennsylvania.

Here is an example of a recorded bird call audio file. Note the closely-spaced spikes which indicate cadence, while the line height shows the pitch of the Whip-poor-will call, another night-migrating species.

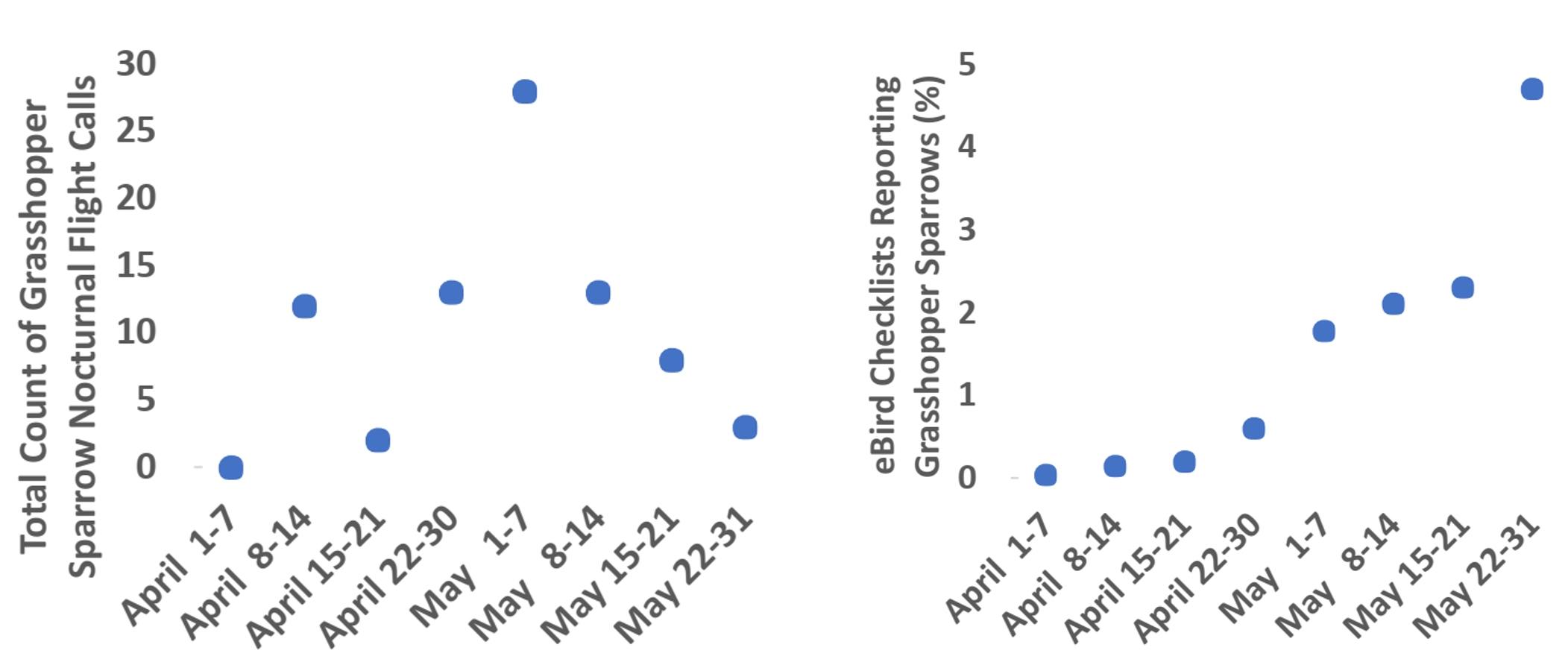

Did the two data sources—recorded nocturnal flight calls and eBird data—indicate the same spring migration arrival pattern for Grasshopper Sparrows? No—not even close!

Grasshopper Sparrows were rarely detected on eBird checklists during the first three weeks of April (eight total checklists), but Grasshopper Sparrow detections increased rapidly throughout May and peaked during the last week of May. In contrast, 34% of the nocturnally-detected Grasshopper Sparrows were recorded during April, and the flight calls indicated a mass arrival of Grasshopper Sparrows starting in mid-April.

Left panel: total number of nocturnal flight call detections for Grasshopper Sparrows monitored at two nocturnal recording stations in Central Pennsylvania between astronomical dusk and astronomical dawn in April and May of 2018. Right panel: proportion of complete traveling or stationary protocol eBird checklists from Union and Centre Counties, Pennsylvania, reporting Grasshopper Sparrows in April and May of 2008-2018.

It’s likely that the early-April surge of Grasshopper Sparrows are mature males arriving in hopes of securing high-quality territories. In many songbird species, adult males initiate migration and arrive earlier than females—a phenomenon called protandry—and older males may arrive earlier than first year individuals.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, then you may recall that I and former VCE biologist, Roz Renfrew, used miniature tracking tags to record the migration of Grasshopper Sparrows. In that pioneering study, Roz and I documented that Grasshopper Sparrows remain on the breeding grounds for nearly a month after other researchers and birders had assumed that most birds had left in autumn. Similarly, we found that the sparrows returned to the breeding grounds in mid-April—a result strongly supported by the nocturnal flight call study. Together, these converging lines of evidence suggest that Grasshopper Sparrows likely arrive on the breeding grounds at least several weeks before they are regularly detected by birders.

So if Grasshopper Sparrows arrive in mid-April, then why do birders not regularly detect this species until the end of May? I suggest a likely combination of two reasons: First, most birders probably avoid grassland habitats in April, either because they’re preoccupied with the return of our colorful warblers and/or they’re under the false assumption that grassland birds have not yet returned. Second, the sparrows that return in April are incredibly secretive—they rarely sing or perch visibly. If you’re lucky enough to flush one, they just fly low above the grass for several meters and drop immediately back to the ground. This behavior makes positive identification nearly impossible for most birders, but tail shape and tail color (what you see as they fly away from you) can be used to separate this species from other sparrows in our region.

If you’re inspired to try recording nocturnal flight calls from your own rooftop, there are plenty of web resources to make it easier, and a great place to start is this primer from our friends at Nemesis Bird.

Joe Gyekis, lead author of this study states, “It’s fascinating to think about the birds that are sneaking by us silently and what else remains unknown, at least until we learn how to pay better attention.”

Reference

Gyekis, J., J.M. Hill, and B. Evans. 2019. Spring migration timing of Grasshopper Sparrows in Central Pennsylvania as estimated from eBird records and two nocturnal flight call stations. Pennsylvania Birds 33(2):89-92

Hi there…..

My name is Melissa West and I am a groundskeeper at Bennington College. The college has some large old meadows that we cut late to allow the field nesting birds their space, and hence we do have a lot of bobolinks and meadowlarks every summer. I have always assumed that we would therefore have the other grassland birds, but I am not enough of a birder to pick them out.

Anyway….would you guys be interested in stopping by next summer to check it out?

That depends Melissa….how good are the maple creemees down there? 😉 To my knowledge, Grasshopper Sparrows don’t breed down in Bennington, but they absolutely pass through there. In the geolocator paper that Roz Renfrew and I published, all of the Grasshopper Sparrows essentially migrated due-north and due-south. Well, Grasshopper Sparrows certainly breed due north of you in NW VT and Canada….so therefore, they likely pass through in mid-April and late September / early October. But they are *really* hard to find/detect during migration unless you get lucky and one decides to land on the college green. They’re not singing during that time. They use a lot of habitats (like early successional shrubby areas) during migration that you and I wouldn’t think of as ‘grasslands’. So I think an April survey might be your best best for detecting this species on the lands that you manage. We might be able to help set you up with a birder (via the Birder Broker program, https://val.vtecostudies.org/projects/birder-broker/) that could help you out. Check out that link. In addition to the Bobolinks (awesome) and Eastern Meadowlarks (double awesome) that you have, I’m sure there are also Savannah Sparrows breeding there. Let’s see if we can make these surveys happen for you! All the best, Jason

Jason, this is a fascinating article. Thank you! I had no idea that the Birder Broker program existed. Can someone who has land in Hanover take advantage of this or is restricted to Vermont? ( hope you are enjoying your tacos tonight!)

Thank you Mary, we had a truly lovely evening at Trail Break last night. I would encourage you to fill out the landowner form (http://val.vtecostudies.org/projects/birder-broker/join-birder-broker/#landownerform) and Nathaniel or Kevin will get back in touch with you. We initially limited the program to Vermont, just so we weren’t overrun in the first year. But I think with so many birders nearby, that we should be able to make this happen for you. All the best, Jason

Thanks for getting back to me Jason. This would not be my property but would be that of a friend’s. I will find out if they are interested.

Good stuff, guys! We did this at Powdermill years ago, comparing the station microphone to the banding data across five seasons for fall SWTHs. In contrast to your findings, we saw almost perfect agreement between the two datasets.

Right on Lewis,

Your experience is also in alignment with the few published comparisons for Catharus species. I’ll hypothesize that there’s good agreement in arrival time estimates for relatively large-bodied and/or colorful species. It’s those cryptic little brown jobbers…where there’s likely the greatest discrepancy. Also, likely a discrepancy for species like American Pipits, who use habitats (barren patches on mountains) that can be physically difficult (i.e., snow covered) for birders to access when the birds pass through.