The summer after I graduated high school, I found a dream job. Kent McFarland had just launched the Vermont Bumble Bee Atlas and needed help tracking down Bumble Bees throughout the state.

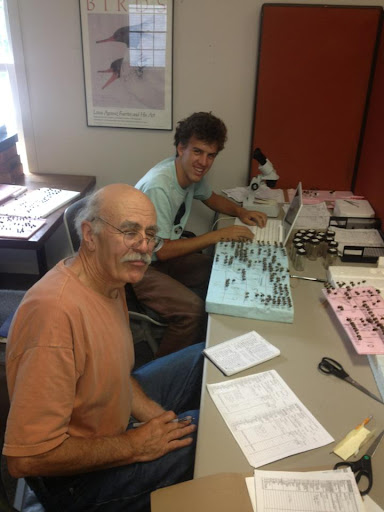

Me and Bumble Bee Atlas volunteer Ed Hack sort through a collection of bumble bees in 2013

That spring, before the job started, I remember paying attention to the fuzzy yellow insects in the yard for the first time – I was astonished to realize that there were multiple different colors and sizes right in my backyard! At a workshop for project volunteers and staff, I remember learning there were in fact at least a dozen species that could be here. I also remember being overwhelmed by how similar some of them looked. For several months that summer and the next, I traversed the state in a car borrowed from my parents. From Georgia to Dummerston and everywhere in between, I sampled bumble bees found along the roadside in predetermined Priority Blocks. By the end of the summer, I had looked at so many bumble bees that I was seeing them when I closed my eyes at the end of the day.

The records I collected, plus thousands more from an army of volunteers and other staff, allowed us to understand the current distribution and abundance and to set a benchmark for monitoring future changes. Prior to the Vermont Bumble Bee Atlas, little was known about this charismatic group in Vermont. Most everything we know about the historical Bumble Bee communities here comes from specimens preserved in museum collections, but even without a lot of data, the changes are shocking. As documented by a 2018 VCE publication and numerous similar studies around the region, there were several bumble bee species that were once common in the northeast, but have vanished in the last part of the 20th century.

Vermont Bumble Bee records in the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. The spike around 2012 is the Vermont Bumble Bee Atlas, with the following increase largely from the proliferation of iNaturalist

In hopes of documenting future changes more rapidly, we are once again counting Bumble Bees. Starting last summer, myself and others have been surveying along the same stretches of road first visited 10+ years ago. By using the same protocols at the same sites, we can track changes in absolute abundance, a previously impossible task. We are also gathering valuable data on phenology, distributions, and floral preferences – not to mention the interesting changes one observes when repeatedly visiting hidden corners of the Green Mountain State – class 4 roads that are no longer passable and new developments in what were once hayfields.

Yellow-banded Bumble Bee (Bombus terricola) – one of several species that was found to be declining by the Vermont Bumble Bee Atlas

With a season and a half of the repeated surveys done, it’s too early to draw any strong conclusions about Bumble Bee populations, but there are some trends already visible that will be synthesized in coming years. It is clearly evident, however, how far we have come as a community interested in insect observation and conservation. In addition to platforms like iNaturalist, there has been a proliferation of resources to help with bumble bee identification in the field and of people interested in protecting these important pollinators. Even less tangible is what I perceive as an increasing awareness and interest from the general public that often stops to chat as I walk back roads with a net in hand. I would call that a conservation success story.

Thank you Spencer