Black Spruce swamp at Steam Mill Brook © Kevin Tolan

Jumping out of my car just prior to five in the morning, I begin to adjust my ears to the morning chorus.

When I had mentioned to people that I planned to do a bird survey in Stannard, most responded, “Where is that?” This small, forested town of 200 people located in Caledonia County, is one of four towns with land in the 11,000-acre Steam Mill Brook Wildlife Management Area. So before I can officially start my bird count, I must do some bushwacking.

Making my way south along an old logging road, I notice the prevalence of Yellow Rattle (an invasive plant I’ve found in hayfields in my grassland birds work) along the overgrown trail. After a quarter mile, the trail opens into an old log landing and I continue forward into uncut growth. A small pond (technically an intermediate fen) not shown on my GPS unit blocks my path, forcing me to backtrack slightly and hike further west.

After trekking through dense shrubs and between downed logs, the underbrush opens into a black spruce swamp and the ambient temperature drops several degrees. This natural community, found in cold, moist pockets, is characterized by a short, dense spruce-fir canopy and a damp understory dominated by sphagnum moss, interspersed with a thin layer of herbaceous plants like Goldthread and Three-seeded Sedge. In an effort to limit damage to the undisturbed moss layer, I follow a trail formed by generations of moose, deer, and bear, and make my way through the shaded understory, at times dodging wet hollows that threaten to swallow my hiking boots whole.

Continuing south and slightly uphill, the sphagnum moss eventually gives way to glades of ferns and dense patches of Wood Nettle. They may be covered in stinging hairs, but the nettles are a welcome sight as an indicator species of rich northern hardwood forest, which develop in areas where nutrient-rich soils form by the downhill (colluvial) movement of minerals and organic matter (colluvium), which collects in benches and gullies in the bedrock. These forests are highly productive, with robust herbaceous layers and an overstory dominated by Sugar Maple, whereas “normal” northern hardwood forests have little herbaceous growth and tend to have more American Beech present.

It’s not until I enter this rich northern hardwood forest that the bird survey can begin. Since 1989, the Forest Bird Monitoring Project, run by our co-founder and biologist emeritus Steve Faccio, has spearheaded bird surveys inside this and other forests, providing a long-term index of our forest bird population trends. Other efforts to track bird populations, such as the USGS Breeding Bird Survey, are performed from road edges rather than forest interiors. But by surveying forest birds within forest blocks, we’re able to more accurately document the status of area-sensitive species that may be less commonly encountered near forest edges.

Now it’s my turn to ensure both FBMP and his vernal pool research continue.

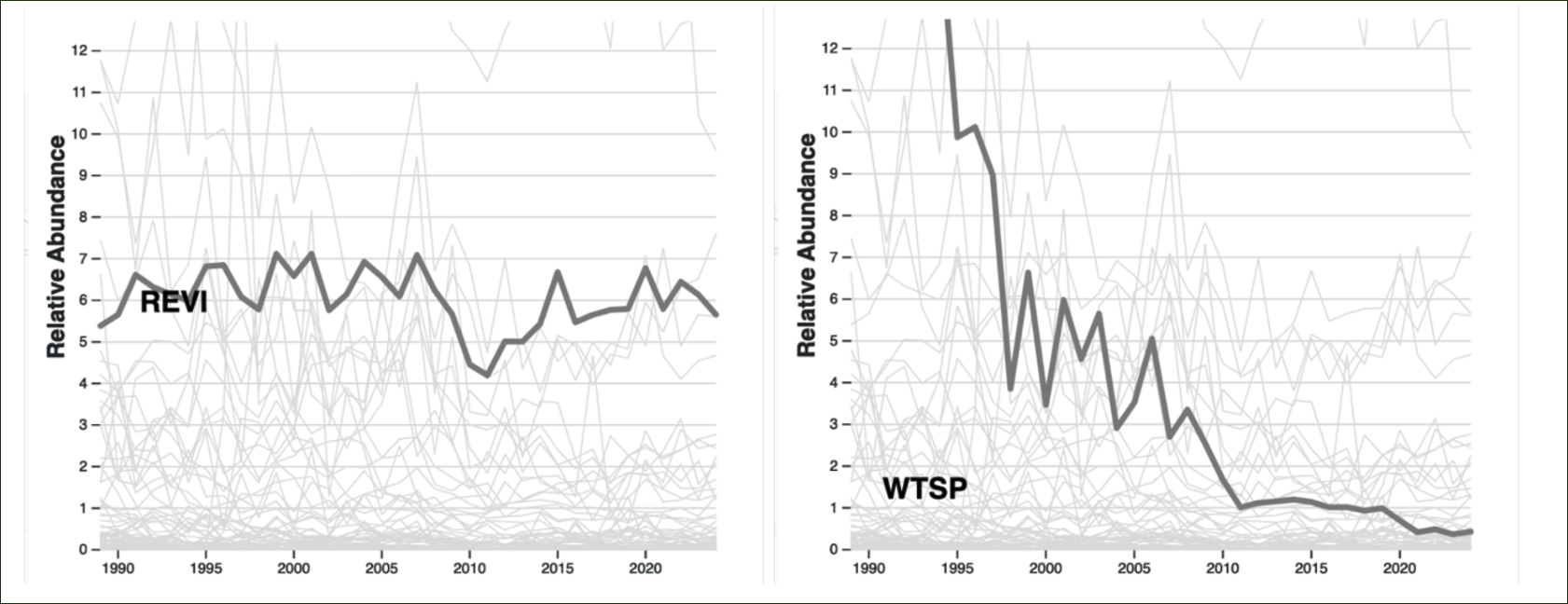

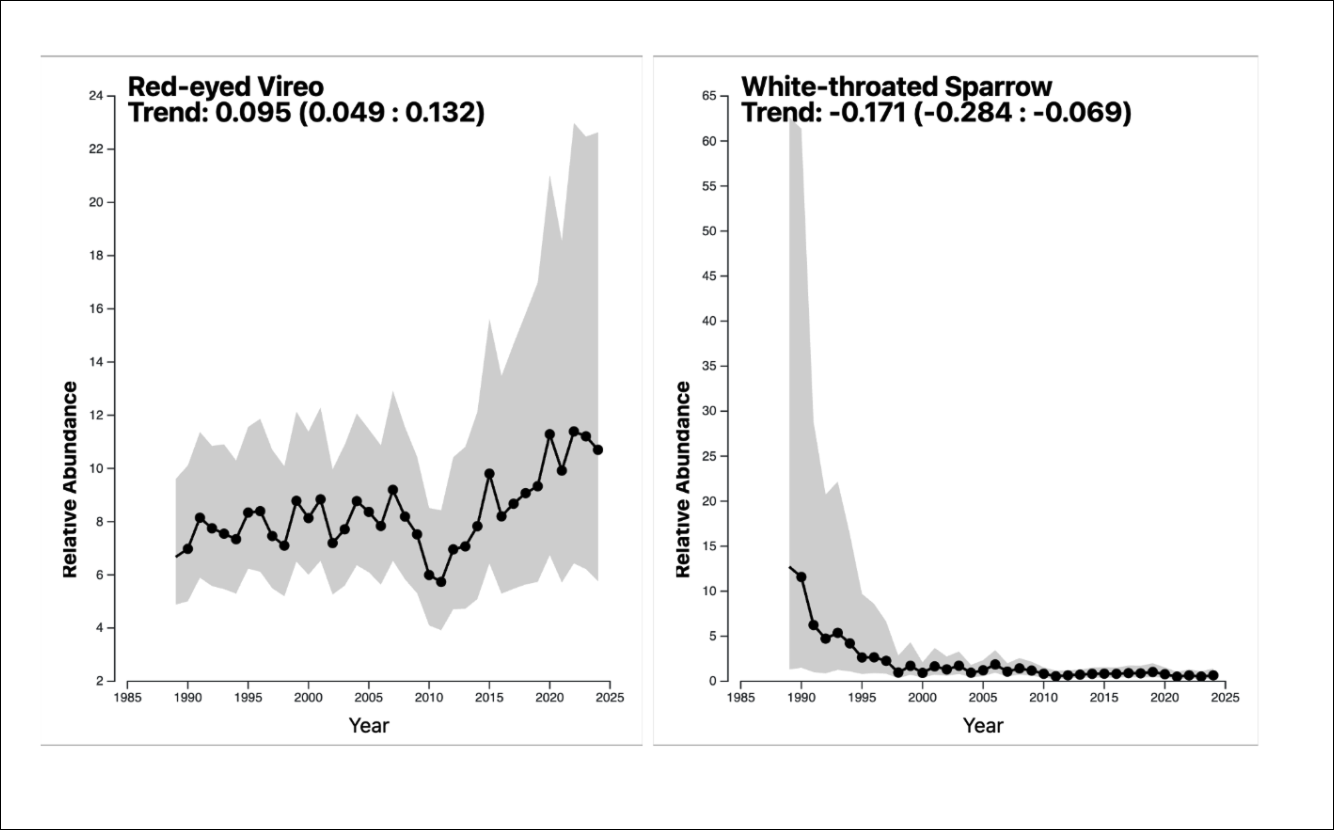

I survey five points, each separated by roughly 200 meters, for 10 minutes apiece by listening for the familiar songs I’ve memorized. Red-eyed Vireos and Ovenbirds, prolific singers that make their presence known, dominate the morning chorus. These two birds are not just two of the most commonly documented birds across our study plots, but also happen to be undergoing estimated annual population increases of 9% and 7%, respectively.

A song that is noticeably absent is that of the White-throated Sparrows. In the early 1990s, more than ten White-throated Sparrows were documented annually on this survey route—more numerous than Red-eyed Vireos. However, in recent years, they’ve been barely hanging on. (You can read more about these trends in the 2017 Status of Vermont’s Forest Birds report.)

Species trends at Steam Mill Brook Wildlife Management Area (1989-2024). Left: Red-eyed Vireo. Right: White-throated Sparrow

Species trends across all Forest Bird Monitoring Project study sites (1989-2024). Left: Red-eyed Vireo. Right: White-throated Sparrow

As I walk between survey points, I think about how loud the bird chorus must have been when the points were first established in 1989, and then how quiet the chorus might become in the coming decades. Forests across the region are threatened by climate change and introduced forest pests. Certain tree species such as American Elm and American Chestnut, have been decimated by fungal diseases and are now absent from most of Vermont’s forests. Insects have also severely impacted our forests, with landowners and foresters around the state trying to mitigate the arrival of Emerald Ash Borer.

A tree species that’s ubiquitous throughout Vermont, American Beech, has been impacted by beech bark disease in Vermont since the 1950s, and is expected to suffer greatly in the coming years by beech leaf disease (BLD). First discovered in Ohio in 2012, this nematode-caused disease was initially detected in Vermont in 2023 and has since spread throughout the southeastern portion of the state—including FBMP routes. While surveying the Little Ascutney Wildlife Management Area FBMP route earlier in the month, I observed signs of BLD at one of my survey points.

BLD appears to disproportionately affect beech saplings, slowing their growth and causing mortality. A reduction in the regeneration of a dominant species, such as beech, can cause drastic shifts in forest composition and structure, which will undoubtedly affect the communities of breeding birds.

Vegetation surveys were done at FBMP plots in 2002, but haven’t occurred since. In the coming years, we have the very valuable opportunity to resurvey the vegetation pre- and post-BLD infestation, allowing us to potentially tie changes in bird community to shifts in vegetation composition and structure.

After having rushed from point-to-point all morning, I conclude the final survey and turn to hike back toward the swamp I had traversed earlier. Slowing down to take in the green-tinted light filtering through the dense canopy, I recall how barren the forest looked during the early-spring vernal pool amphibian breeding season. While the salamanders are currently out of sight in a subterranean network of burrows, they too rely on a healthy forest to provide shade to the forest floor, maintaining adequate moisture levels.

As our forests face increased threats, on-the-ground research and conservation is needed more than ever. Steve Faccio has some big shoes (and a big shelf of awards) to fill, but I’m eager to build on his legacy and make new discoveries that will aid in protecting these precious areas, plus the singing birds and Spotted Salamanders that live in them.

Hooray!

Wonderful article, Kevin. We are lucky you are continuing Steve Faccio’s projects. Thank you!

great to read your report Kevin. Steam Mill Brook is special.

Thank you for this report, Kevin! This is excellent work that needs to be continued. How else will we be able to understand the longterm changes happening to these ecosystems and what we can do to maintain diversity in our forests.