Pictured left to right: Inez Hein, Dana Timms, and Alison Nevins. Each of them are holding a Grasshopper Sparrow at Fort McCoy, Wisconsin. / © Sue Vos.

Studying birds that nest in grasslands on the firing ranges and runways of active military installations is not for the faint of heart, but it proved to be a successful strategy to help solve some perplexing migration mysteries.

Basic questions regarding the timing and choice of migration routes, and what that means for conservation of grassland bird populations have been surprisingly difficult to answer—until now. Research by VCE biologists recently published in Ecology and Evolution sheds light on the annual movements of two grassland bird species and yields surprising results that may help transform the way we manage grassland bird populations, both across international borders and throughout their annual cycle.

With support from the U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program, VCE’s Jason Hill and Rosalind Renfrew carried out the most extensive examination of the nonbreeding movement ecology for Grasshopper Sparrows (Ammodramus savannarum) and Eastern Meadowlarks (Sturnella magna) to date. Filling in fundamental knowledge gaps, their research will pave the way for cooperative endeavors to slow the decline of these grassland birds in the Midwest and Eastern United States.

To investigate the migratory patterns of these two species, Jason and Roz—with help from field crews, colleagues, and installation managers—captured and fitted backpack-style geolocators on 180 Grasshopper Sparrows and 29 Eastern Meadowlarks at Konza Prairie in Kansas, and at six U.S. Department of Defense installations across the species’ breeding ranges.

An adult male Grasshopper Sparrow at Camp Grafton, North Dakota, wears a light-level geolocator that will help reveal his annual migration route and overwintering area. / © Alexandra Lehner

While that sounds difficult enough, the really hard part was re-capturing the very same Grasshopper Sparrows one year later to remove those geolocators and download their data! Eastern Meadowlark backpacks, thankfully, transmitted data through satellites. The team was able to retrieve location data on 34 Grasshopper Sparrows and five Eastern Meadowlarks.

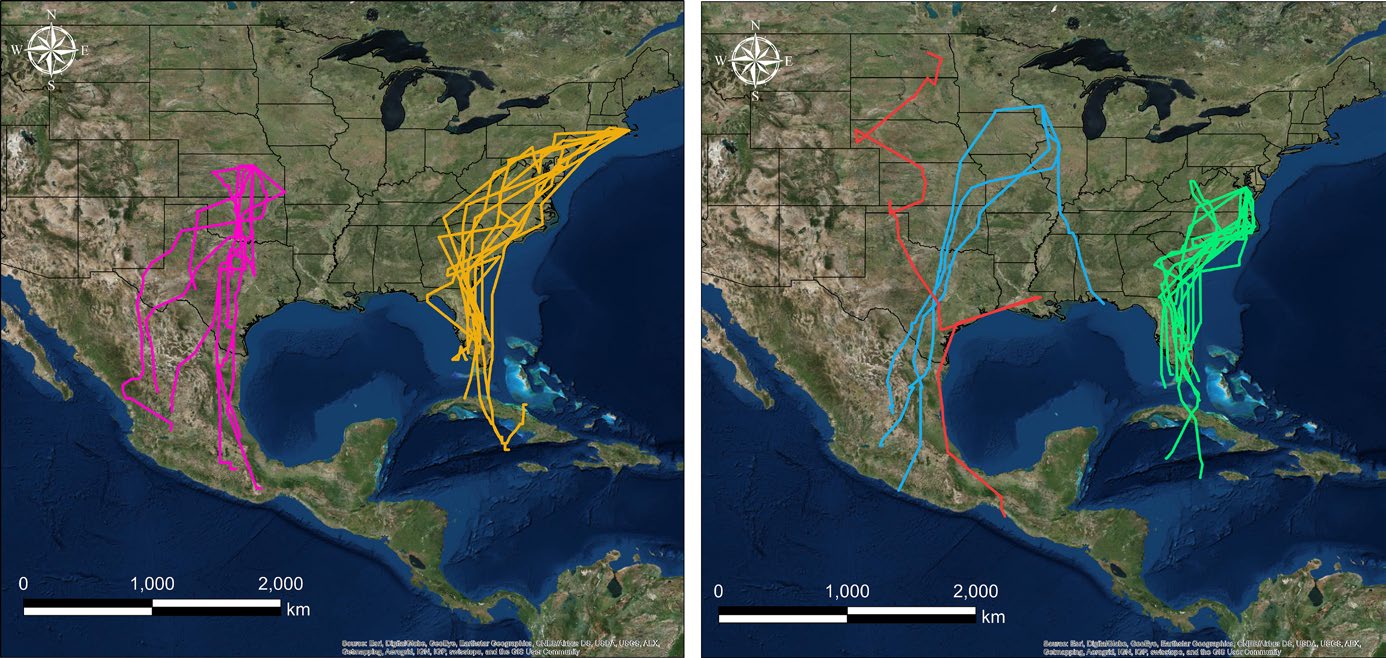

Data retrieved from the geolocators held many surprises. Among the most astonishing findings was that Grasshopper Sparrows do not begin fall migration in August as biologists had previously assumed; they actually stay put on the breeding grounds until October. The data also revealed that Grasshopper Sparrows make short, nearly daily migration flights, and that the North American Great Lakes region likely serves as a migratory divide between Midwest and East Coast populations. Data from Eastern Meadowlarks provided evidence of a diversity of individual movement behaviors, ranging from year-round residency in the same location to short‐ and long‐distance migration strategies.

Each line represents the most probable fall migration route for Grasshopper Sparrows from breeding populations in Kansas (purple, n = 8) and Massachusetts (orange, n = 10; left panel) and North Dakota (red, n = 1), Wisconsin (blue, n = 4), and Maryland (green, n = 10; right panel). Grasshopper Sparrows from the Midwest almost exclusively overwintered in Texas and Mexico, whereas sparrows from the eastern U.S. overwintered in Florida or the Caribbean.

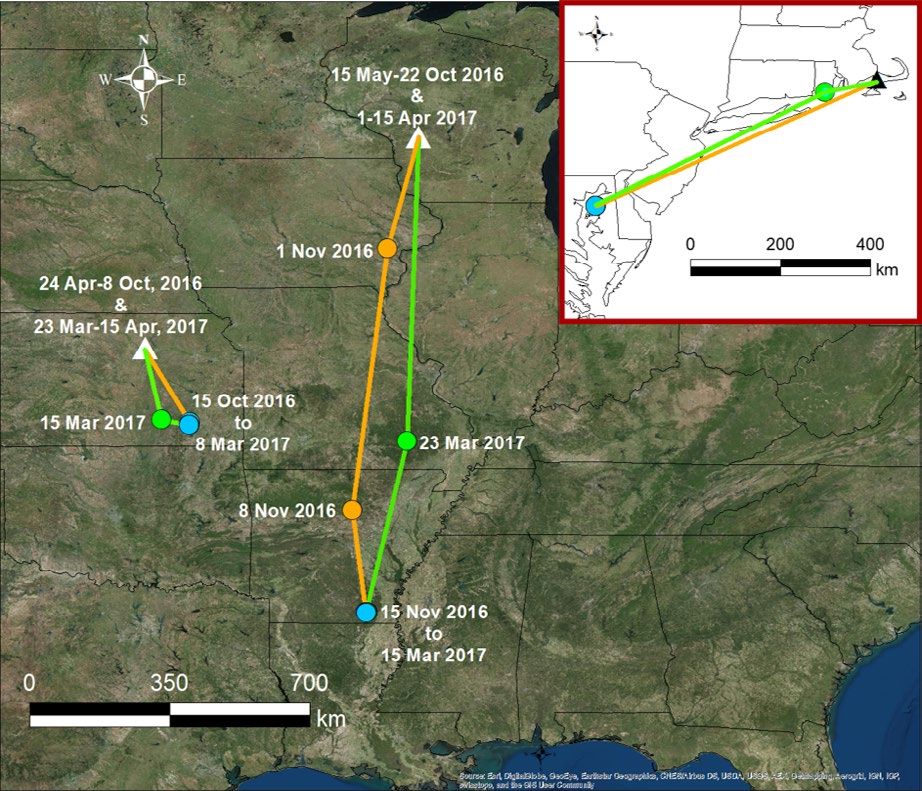

GPS tag locations (circles) during fall (orange) and spring (green) migration, and the nonbreeding period (blue) from Eastern Meadowlarks originally tagged at Department of Defense installations (triangles) in Kansas and Wisconsin (main panel), and Massachusetts (inset). Colored lines represent probable and approximate flight paths between consecutive (~1–2 weeks apart) locations. Not shown are two meadowlarks tagged in Maryland that were non‐migratory year‐round residents.

The study reveals where and when these grassland birds travel each year between their breeding seasons, and highlights where research is needed on the stopover and nonbreeding grounds, especially for Grasshopper Sparrows in Mexico and the Caribbean Islands. For an immersive experience, you can interact with those results on VCE’s Grassland Bird Migration Project page.

As both an ornithologist and a serious birder, I (like many experienced birders) have never considered GRSP to be an early-fall migrant. The eBird occurrence map of September seems to support my beliefs and the results of this study:

https://ebird.org/map/graspa?neg=true&env.minX=&env.minY=&env.maxX=&env.maxY=&zh=false&gp=false&ev=Z&mr=on&bmo=9&emo=9&yr=all&byr=1900&eyr=2019

Notice particularly the density (darker purple) in the northern prairies in Sep.

Tony,

Good to hear from you (outside of the eBird editor discussion group). Yes, I’m with you. It’s a detection issue. First, there just are many birders chasing brown grassland sparrows (e.g., Grasshopper and Henslow’s Sparrows) early and late in the season. In PA (where I did my PhD with GRSP) I usually reported the first GRSP for the state each year in the spring and once the last sparrow in the fall. I wasn’t trying to, per se, just checking in on my study plots and accidentally flushing small brown birds from the grass who would immediately drop back down into the grass. That tells you how little effort was expended by other birds intentionally looking for grassland sparrows. From my mark-recapture study, I learned to ID grassland sparrows from tail shape and color (seen while flying away and diving into the grass) during these quick encounters. Second, they are hard to detect when not singing and easily overlooked. eBird used to have those moving STEM maps up for GRSP, but I believe they’re no longer online. They put a disclaimer on the Grasshopper Sparrow map at the bottom mentioning something like, “Yes, it looks like this species disappears in August on the breeding grounds, but this may stem from low detection rates.” Lots of work to be done with this species on the wintering grounds in Florida, and south of the U.S. border. eBird observations from Honduras down through Columbia, have greatly expanded the southern end of the range map for this species over the last 20 years.