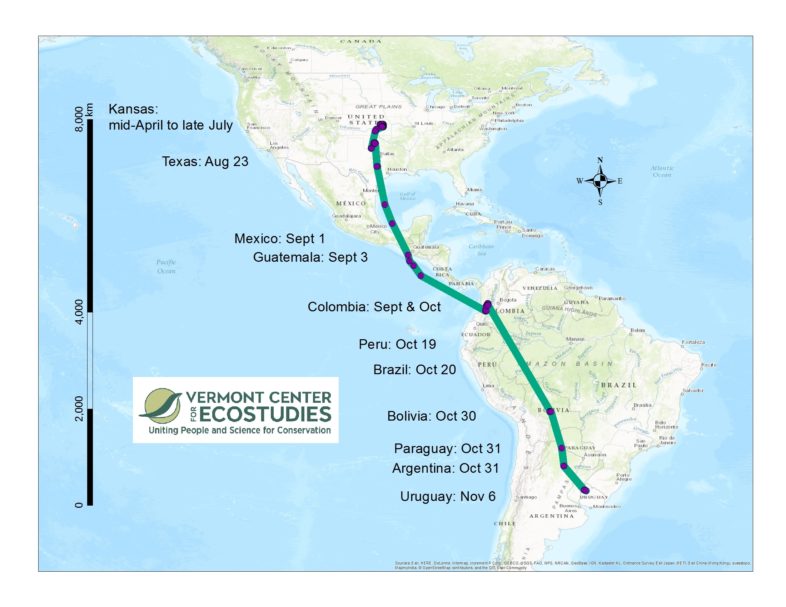

The fall 2016 migration route (>10,000 km, so far) of an Upland Sandpiper that bred in Kansas. This Upland Sandpiper was fitted with a solar-powered satellite tag in April, 2016 at Konza Prairie, Kansas. Since leaving Kansas in July, she has visited nine additional countries on her southward journey. Map created in ArcGIS.

The results of our grassland bird research partnership with the Department of Defense Legacy Program have been eye-opening. This past summer we outfitted 15 Upland Sandpipers with satellite tags at military bases in Massachusetts (Joint Base Cape Cod and Westover Air Reserve Base) and Fort Riley and Konza Prairie Biological Station in Kansas. Four of those sandpipers received solar-powered tags that send us their daily location via email. Yes, you read that correctly—Upland Sandpipers can now send email (or at least their tags can).

Our satellite tags have provided the first direct observations of the pathways that these sandpipers take upon leaving their breeding grounds. We have already learned that these birds use a multitude of private properties, especially agricultural fields, on their southward journey. Two of these tagged sandpipers flew non-stop from the Northeast US over part of the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea to Venezuela, and another sandpiper (see map) flew non-stop from Texas to Colombia while crossing the Gulf of Mexico and skipping over the Pacific Ocean. We captured and tagged this female sandpiper in April, 2016, at Konza Prairie Biological Station in Kansas with our colleague Brett Sandercock (Kansas State University), and since then she has visited nine other countries. In late July she started moving southward across the plains of Oklahoma and Texas, crossing Mexico in September, flying over the Amazon basin in October, and reaching Uruguay in November. That’s a one-way journey of >10,000 km.

Next, we will attempt to contact the managers of the parks and reserves that our Kansas Upland Sandpiper used on her southward journey. A primary goal of our research is to serve as a catalyst in coordinating conservation actions and management of this vulnerable species throughout its entire life cycle and across its year-round range.