As bald eagle nests become more common in Vermont, the Fish & Wildlife Department is asking bird-watchers to enjoy the birds from a safe distance to avoid disturbing them.

Photo by John Hall, Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department.

Vermont’s Bald Eagle population continued its recovery in 2017. Twenty-one pairs of adult Bald Eagles successfully produced 35 young in Vermont in 2017, a modern-day record in the state according to the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. The species remains on Vermont’s endangered species list, but another strong year of growth has biologists hopeful for their continued recovery.

Bald Eagles typically nest along significant water bodies where fish and other aquatic foods are readily available. In Vermont, most bald eagle nests are found along the Connecticut River, Lake Champlain, Lake Memphremagog, and some other large inland bodies of water.

In 2002, the first Vermont eagle nest was discovered after a 60-year absence. However, it wasn’t until 2008 when the first eagle fledgling successfully left its nest. Eagle numbers have been steadily increasing since then, giving hope to their full recovery in the near future.

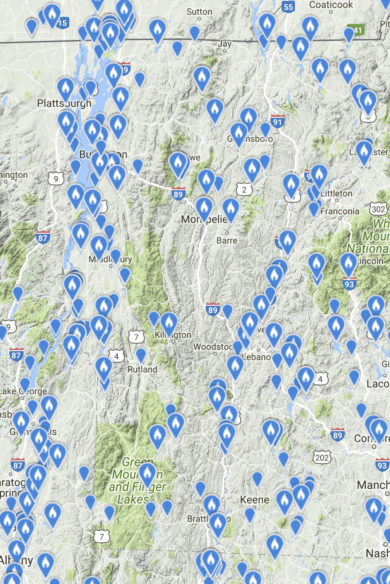

Bald Eagle sightings reported to Vermont eBird during the summer of 2017. Click on the image to view a live map at Vermont eBird.

“Vermont’s Bald Eagles continue to recover thanks to improved habitat conditions, especially water quality and forested shorelines. These conservation efforts would not be successful without the interest and support of the public for these nesting areas by maintaining a respectful distance from the nests,” said John Buck, bird biologist for Vermont Fish & Wildlife. “People have reported seeing large numbers of Bald Eagles migrating through the state, including many juvenile eagles that have remained in Vermont and may someday nest here.”

Peregrine Falcons successfully raised at least 63 young birds in 2017, according to Audubon Vermont who monitors nesting peregrine falcons in partnership with the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. This is similar to nesting success from previous years, though down slightly from a record high in 2016. You can view a map on Vermont eBird of Peregrine Falcon sightings and add your own.

Peregrine Falcons and Bald Eagles declined in the 20th century nationwide due to loss of habitat, disturbance to nests, and the effects of the pesticide DDT. Laws such as the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and a ban on DDT have aided in the recovery of these birds. Loons similarly faced dramatic declines as a result of shoreline development and human disturbance of their habitat.

In 2005, Peregrine Falcons, Common Loons, and Osprey were removed from Vermont’s state endangered species list following years of conservation effort. Bald Eagles have recovered in most of the U.S., but remain on Vermont’s state endangered species list as they continue to recover locally.

“Vermonters have played a huge role in the recovery of these species,” said Margaret Fowle, biologist with Audubon Vermont. “We work with a large number of citizen volunteers who help monitor nests, while the general public has aided in recovery efforts by maintaining a respectful distance from these birds during the critical nesting season. Paddlers have been keeping away from nesting loons, and the climbing community has been helpful by respecting peregrine falcon nesting cliff closures and getting the word out about where the birds are.”

Common Terns, another state endangered bird species being monitored by biologists, fledged 71 chicks in 2017. Predation and erratic weather during the hatching period probably accounts for the average nesting result.

Vermont also welcomed 93 newly fledged birds to the state’s Common Loon population, breaking the previous record of 81, according to the Vermont Center for Ecostudies who monitoring and manage loons in partnership with the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department.

Source: VFWD press release