Weathering Whitcomb for Mountain Birdwatch

By Tara Rodkey, VCE’s Alexander Dickey Conservation Intern

(All photos courtesy of Tara Rodkey unless otherwise noted.)

Pollen and seed spiraled over the car, yellow flakes spattering the windshield, as we drove over the meter tall grasses on the two-track road. The accordion and a plucking Spanish guitar play on my radio, Lucha Reyes’s voice rising over the crunch of rocks under the tires and the swishing of the grass swinging upright behind our wheels. It is the end of June, and our final days to complete Mountain Birdwatch routes are accompanied by a stifling wet heat and chances of rain in most of the survey areas. Alex Kulungian (VCE’s UVM Rubenstein School Perennial Summer Intern) and I have driven up to northern New Hampshire to survey Whitcomb Mountain, one of the few enclaves of sunny-day forecast. Whitcomb is in the middle of an inactive logging zone, and the route doesn’t follow a trail per se, but an overgrown road. Under the bed of wildflowers and grass, the ditches and bumps in the road are getting rougher, and we stop just a mile short of the first observation point, unwilling to test my old ‘04 Subaru any further. We get out of the car and throw on our daypacks to go scout the route.

It’s 3 o’clock, and the high summer sun has already started down its journey westward. But the heat still sticks to our bodies and I am grateful for the head net I have brought with me, as black flies and mosquitoes are too eager to plaster themselves to our sweat. We wade through the grasses, the meadow grazing our waists, and start up the slope, grasshoppers flitting ahead of our footsteps. Reaching the first three points isn’t difficult, and we spend some time puzzling together the GPS coordinates with the site descriptions:

– Does this look like a “small copse of spruce” to you?

– Oh! That must be that fir, it just fell down since this picture was taken.

– This has to be that boulder but it’s definitely not three meters high.

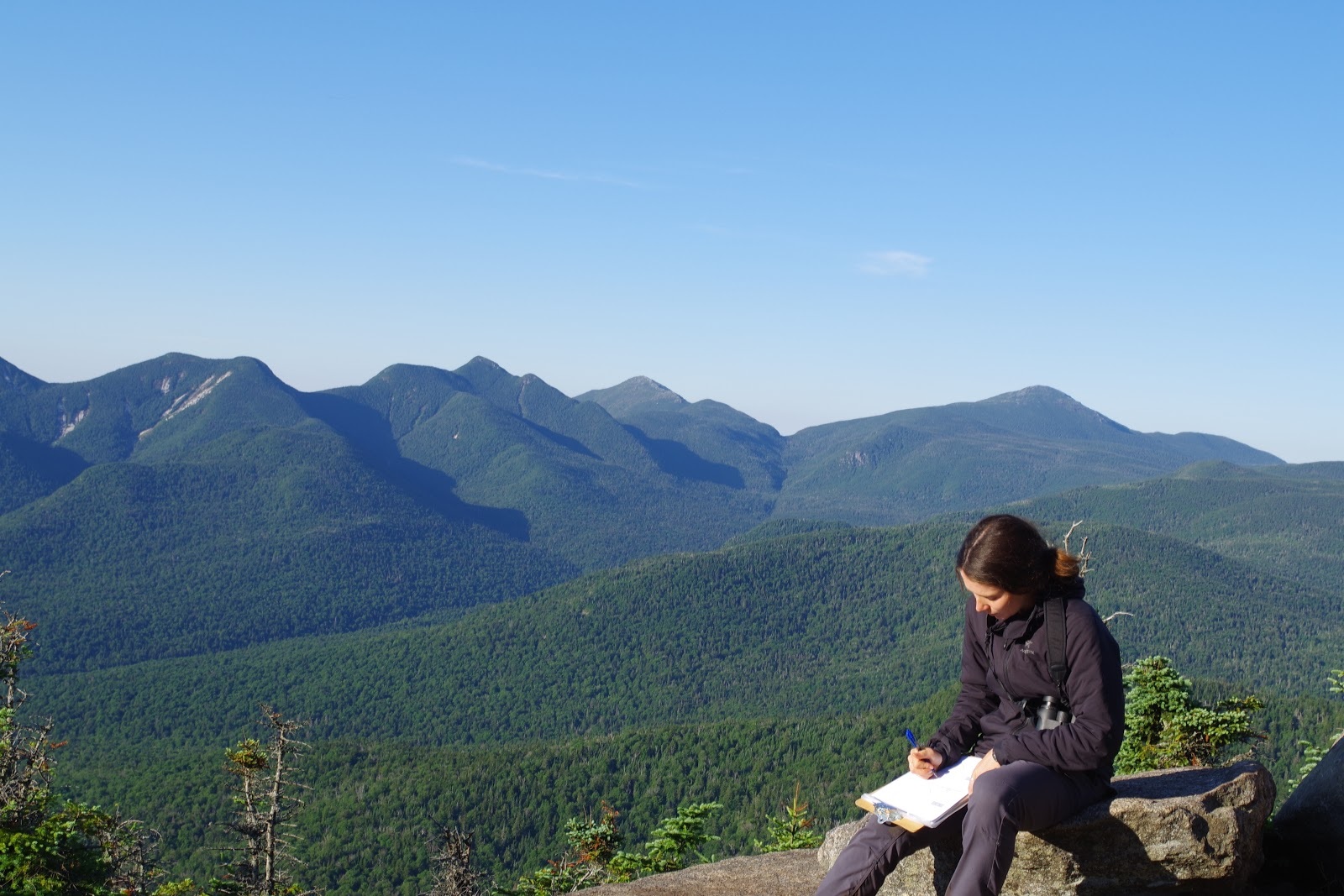

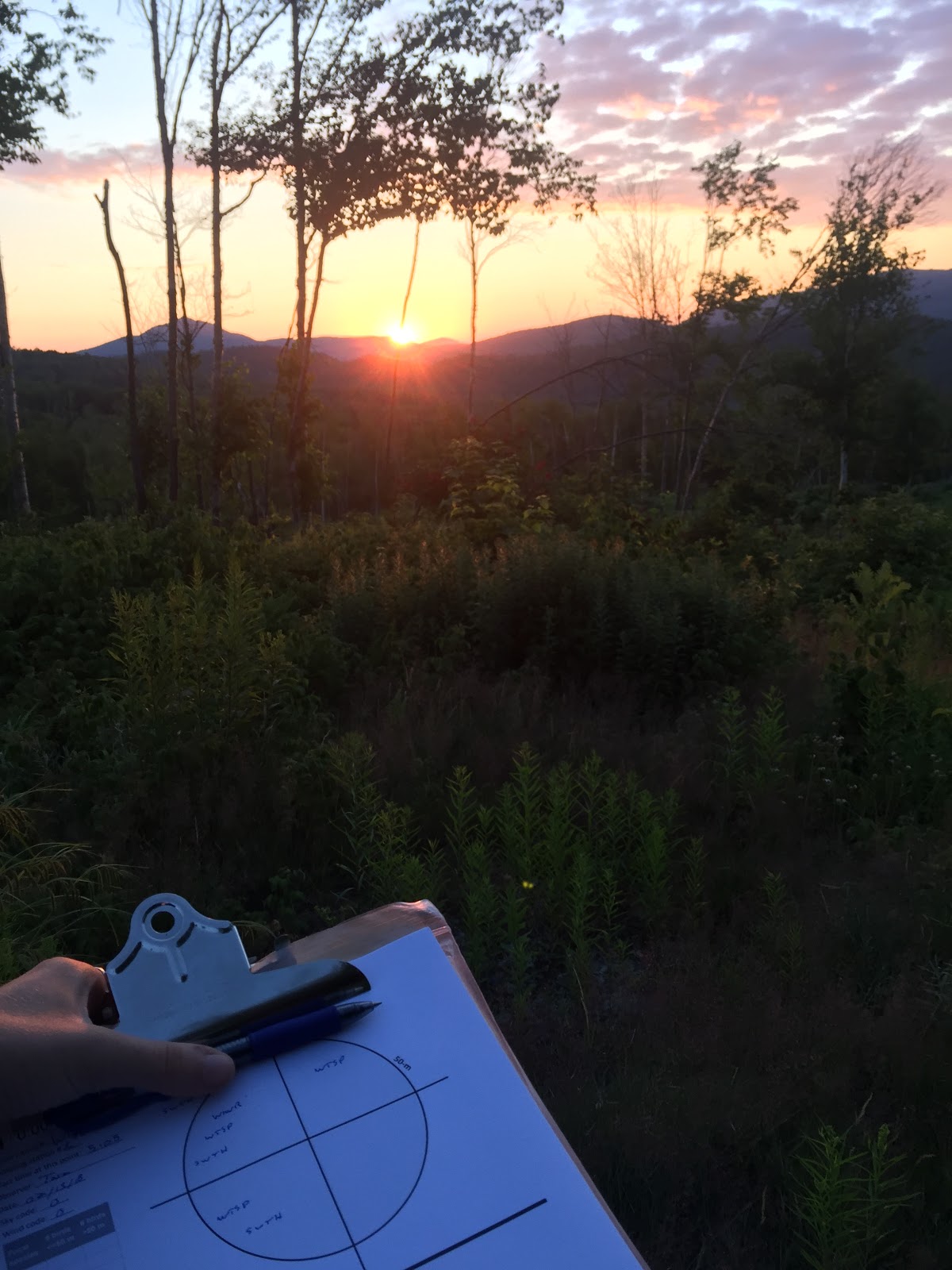

A month into the project, this kind of detective work had become quite practiced for us. Mountain Birdwatch is a program in which citizen scientists volunteer their time to monitor specific montane bird species throughout the Northeast’s high spruce-fir forests. Volunteers hike in to points on trails at the crack of dawn where they record any of the focal bird songs and calls that they hear during a twenty-minute interval. Besides filling in the gaps and covering routes not yet adopted, or those whose volunteers’ good intentions were thwarted by life’s last minute curve balls, my partner Alex and I had been working on improving the descriptions of all the routes for the project—numbering over 100—hopefully to remove some of the doubt and investigative work for future Mountain Birdwatch volunteers.

Through the fern clearing to the next points, the path only gets wetter, following a little-used offshoot of the old track. Our feet squeeze the water out of the soles of our shoes with every step now. Late afternoon, the air is quiet, a summer stillness marked only by insect chatter, and I wonder what kinds of birds we will hear at these points at dawn tomorrow.

I finish writing a description for the final point, and we head back down to the car to set up camp. It is 6 o’clock and the clear weather forecast looks like it is holding true, a blue sky with short tame clouds sitting lightly above us. Dinner is a quick can of beans and then I set up my tent behind the car and throw in some books before checking myself for ticks and turning in for the night. Alex sleeps in the passenger seat of my car, not wont to hazard any more contact with ticks than need be. The clouds have all but disappeared and I leave the fly off my tent to catch the breeze and the dusk sky. There is some snapping of tree limbs in the woods just off the road, followed by breathy snorts, and I indulge in imagining who our evening neighbor might be—a moose, coming to graze around the new-soaked ground? Whoever she may have been, she was wary of the two unsightly “boulders” that had appeared in her haunt of the woods and she soon ran off. After setting an alarm for 3 a.m., I read myself to sleep as the light waned.

A flash of blue wakes me up. I sit still in my tent, listening. My watch reads 10 o’clock and the night is silent. After a few moments of waiting, a couple lightning bugs drift over, flashing blue, and I start to relax back into sleep. But, sure enough, a low grumble rips through the sky. The night lights up again in a spastic display of pastel blue. Undoubtedly not lightning bugs. I sit up on my mat and listen for thunder. Once again, lightning streaked across the sky, over and over in short succession, illuminating the sky so much it felt like the darkness was flashing around us. The night before, we had been poured on in the White Mountains well into the morning, and we had come off the mountain empty-handed and soaked, leading us to take our chances north, here. I hoped that we were just seeing storms passing over the southern range, and that we wouldn’t be rained out of yet another survey. But for this night, I wasn’t taking any chances. I grabbed my books and sleeping bag and jumped into the back my car, rudely awakening my partner as we scrambled to rearrange our gear in the dark. In this bubble of safety, I fell asleep to the azure bursts of light, listening to the grumble grow further and further south.

Our last morning of June was a clear dawn, with not a brush of wind, and air moist and refreshed from the evening spectacle. A chorus of the wavering whistles of White-throated Sparrows echoed across the mountaintop, joined by Winter Wrens, the tapering trill of Blackpoll warblers, and one other particular voice—the skidding harmony of a singular Bicknell’s Thrush.