VCE bird bander Anne Peel holds a Bicknell’s Thrush on Mount Mansfield. © Alden Wicker

“I suppose you could say I have a love hate relationship with this bird.”

Chris Rimmer, a co-founder and director emeritus of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, says this as he sits on the front porch of his Vermont home, a five-minute drive from VCE’s White River Junction offices. He has the relaxed bearing of a retired mountaineer: fit and weathered. And in some sense, he is just that.

If you’re new to our community, you might not know that Rimmer’s career has been wrapped around a little brown bird that spends its summers hiding out near the top of the Northeast’s highest peaks.

“It’s one of the most difficult songbirds that anyone could attempt to study,” Rimmer explains. “It’s on these mountaintops that are hard to get to. The weather can be harsh. The blackflies can be horrendous. The habitat is virtually impenetrable. The thickets of fir and spruce are often wet. We’ve had snow in June up there.”

Aside from its mountaintop fortress of a home, the bird itself isn’t showy. “It’s about as drab as a bird can get. It’s got no colors on it except somber grayish brown and white. It’s reclusive, enigmatic, hard to get to know,” he continues. “It’s a crepuscular species—the hours in which it’s most active are dawn and dusk.” That means biologists who want to study it are awake from as early as 3 a.m. to at least 9 p.m.

“I should have studied robins,” Rimmer says. “I would have learned a lot more, had a much bigger sample size, and many fewer gray hairs.”

But he doesn’t mean that. There’s a reason people scale mountains: to satisfy their curiosity about what’s up there, to prove to themselves they can, to get a view across hundreds of miles of varying ecosystems and plot a safe path across them, to lift themselves out of the every day and experience awe. In that sense, Bicknell’s Thrush (birder shorthand: BITH) delivers for Rimmer and the many birders and biologists who have come to both respect this bird and fight to protect its habitats in the northern mountains and cloud forests of the Caribbean.

What’s Up with This Bird?

In 1992, Rimmer was a songbird specialist working at Vermont Institute of Natural Science (VINS) when he attended an annual meeting of the American Ornithologists Union (now the American Ornithological Society) in Montreal. A Canadian zoogeographer named Henri Ouellet presented a paper exploring whether Bicknell’s Thrush, which had been categorized as a subspecies of Gray-cheeked Thrush, should be classified as a distinct species.

Discovered by amateur ornithologist Eugene Bicknell in the Catskills in June 1881, Bicknell’s Thrush looks so similar to Gray-cheeked that if you see them during migration, “you can not reliably tell them apart,” Rimmer says.

But Ouellet noted that their ranges were completely non-overlapping, both where they breed and overwinter. “He looked at museum specimens. He went out in the field and recorded their songs and played them back to each other, finally looked at their DNA, and concluded it was a separate species.”

Rimmer was intrigued. BITH bred nearby in the Green and White Mountains, but “We didn’t know anything about this bird: how many there were, where they occurred on the landscape…we certainly didn’t know how they were doing.”

Meanwhile, these rare mountaintop ecosystems that this little brown bird relies on—island-like habitats of spruce-fir forest above 3,000 feet in the Catskills, Adirondacks, Green Mountains, and White Mountains—were getting doused with acid precipitation and mercury pollution as developers were trying to expand ski resorts and site wind turbines.

Their wintering range is confined to four islands in the Caribbean, where they inhabit broadleaf forest from sea level to the highest mountains, with most of the birds living in the Dominican Republic.

Chris Rimmer, Steve Faccio and team in the Dominican Republic in 1997 © Kent McFarland

Their sea-level habitats “have been hammered,” Rimmer says, lost and degraded to development and agriculture. He decided: “We gotta figure out what’s up with this bird.”

Rimmer and his colleagues scoured the literature to come up with 73 mountain peaks where Bicknell’s Thrush had historically been documented. They then invited community scientists to perform hiking surveys in June during 1992 and 1993 on more than 300 different peaks to see if the species was there, equipping the volunteers with playback (BITH song tapes and speakers) to tease them out of hiding.

The Bicknell’s song is thrushlike, but not melodious. “You can’t put words to it,” says Rimmer, who calls it “magnificent. It fits the setting. It’s a descending, spiraling, rich—but not complex—song. It goes down the scale and up at the end. It’s a little bit dissonant.” During courtship and nesting season, BITH also vocalizes with a call that sounds like “BEER! BEER!”

“I did some surveys myself, but we could have never done what we did without community scientists,” Rimmer says. Together they found Bicknell’s Thrush on 63 of the 73 peaks where it had been historically found, which was encouraging. Surveying by ear didn’t tell them how many birds each peak had, but at least the birds were still there.

Rimmer and his team then established a study site on Mount Mansfield to study the bird’s breeding ecology before expanding to Stratton for an annual eight-week period of intensive study on each peak. Many young biologists and ornithologists, including VCE Associate Director Dan Lambert and Caribbean Conservation Coordinator Jim Goetz, got their start on those mountaintops, bonding over the grueling work. “It was so so hard, getting up at three in the morning, getting yourself beat up all day, and coming in at night exhausted,” Rimmer says.

“But we would have a beer, tell stories, laugh, go to bed, get four hours of sleep, and get up and do it again.”

They captured and tagged birds, color-banding them so they could track individuals, and placing lightweight backpacks with radiotelemetry tags to monitor their activities on the mountains and in the D.R. Later, they added GPS tags to track their precise movements during migration.

There are few reasons to get up to see the sunrise on New England’s highest peaks day after day. BITH provided one that has endured for more than 30 years. “There are times it’s truly magical,” Rimmer says. “You’re up there, clouds are sweeping across the mountaintop, dawn is coming, and there is birdsong all around you.” During courtship at dusk, the male BITHs will put on a moving show, tracing big circles 50 to100 feet up in the sky as they sing.

A Bird Flaps Its Wings…

Rimmer calls VCE co-founder Kent McFarland “my absolute co-pilot in the early years of this work.” The year they broke away from VINS to found VCE, they established the International Bicknell’s Thrush Conservation Group (IBTCG), which included partners from the Dominican Republic, Canada, American government agencies, and academia.

Chris Rimmer holding a Bicknell’s Thrush with Kent McFarland © Kent McFarland

They quickly established an action plan for Bicknell’s Thrush conservation. The goal was to increase the population of BITH by 50% by 2060 and not suffer any net loss of its breeding range. The action plan has been through a revision, and Goetz, who is now IBTCG’s head, is working on a second revision.

The conservation inspired by Bicknell’sThrush has benefited many other species that also rely on high-elevation habitats. Data collected by Mountain Birdwatch, a VCE monitoring program for ten montane songbirds that grew out of the BITH study, has led to the delineation of Bird Conservation Areas in the Adirondacks and Catskills, and spurred conservation of important properties in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Other North American wildlife that have benefited from BITH-focused conservation include Canada Lynx, Northern Spring Salamanders, American Three-toed Woodpeckers, Blackpoll Warblers, Boreal Chickadees, Olive-sided Flycatchers, and Purple Finches.

Studying this bird also led Rimmer and his colleagues to the Caribbean, where they’ve worked with locals in Cuba and Hispaniola who have gone on to have careers in conservation and biology. While they’ve been studying Bicknell’s Thrush, they’ve also monitored and built new knowledge of endemic birds that occur nowhere else but the cloud forests of Hispaniola. For example, they published the first nest descriptions for two Hispaniolan songbirds: the Western Chat-tanager and the Hispaniolan Highland-tanager. “We’ve created a lot more awareness. The locals really care about ‘their’ birds that are unique to the island,” Rimmer says.

There is also now a private park in the D.R. because of Bicknell’s Thrush: Reserva Privada Zorzal (zorzal means thrush in Spanish). It is the Dominican Republic’s first private reserve. Because public reserves receive little protection in practice by the resource-poor Dominican government (for example, avocado plantations encroach with impunity in one key national park), IBTCG partnered with a young anthropologist and forester named Chuck Kerchner and a wealthy Dominican family to protect 1,019 acres.

Seventy-five percent of those acres have been designated as forever wild and are being carefully restored to lush Bicknell’s Thrush habitat, while the rest have been turned over to sustainable, bird-friendly cacao farming.

One local ornithologist, Hodali Almonte, did her master’s research on Reserva Zorzal and found that the population of BITH in the reserve has increased in the past seven years.

Studying Bicknell’s Thrush has “shown me how compellingly linked events in the natural world are across space, in particular for a migratory animal,” Rimmer says.

For him, it was never just about the bird. “I love the bird, and love being in these beautiful, wild places. But conservation is ultimately about people and changing their behavior in ways that will benefit the natural world. That’s really been one of the most fulfilling parts of the work for me—just being on Mount Mansfield and having groups of visitors come by the banding station, showing little kids a bird in the hand and letting them release one.”

Now Bicknell’s Thrush faces the metathreat: climate change. As the world warms, the conifers necessary for Bicknell’s Thrush reproduction are expected to retreat up the mountain, shrinking these islands of habitat until some disappear. Rimmer worries that in100 years, only the highest, most northern mountain peaks will still hear the song of this rare little brown bird. “Inaction is not an option or it will go extinct. It might anyway,” he says.

Seasonal VCE Bird Bander Anna Peel shows off a Bicknell’s Thrush she banded in the summer of 2025. © Alden Wicker

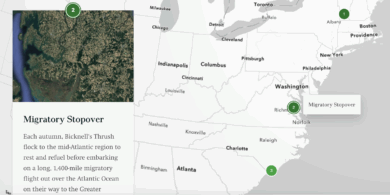

McFarland’s research interests eventually diverged to focus on butterflies and other pollinators, which requires that he only go out with a net on beautiful, sunny days. But a new BITH team is now camping at the top of Mount Mansfield each summer and then traveling to the D.R. Principal Investigator Desirée Narango, along with Mike Hallworth and Goetz, are building on the foundational work from Rimmer, McFarland, and others to fill in some of the gaps in our understanding of Bicknell’s Thrush. They’re using tracking technology to illuminate the movement ecology of female thrushes in hopes of identifying where in the annual cycle they’re not surviving, determining diet and prey selection during the breeding and wintering seasons, and piloting the first study of habitat selection during migratory stopover in the Mid-Atlantic.

Explore more about current BITH research in our interactive Story Map: Silent Summits

That Bicknell’s Thrush demands such sacrifice, commitment, and, increasingly, faith may be the reason it has changed the lives of so many people, and along the way improved the prospects of other vulnerable species with which it shares the forest at both ends of its migratory range.

Read the entire Fall 2025 issue of Field Notes, fresh off the press, here. If you would like to receive a physical copy of the magazine, email .