Hartford, VT – Calling all birders: Are you experiencing migration burnout? Tired of warbler neck? Is the cost of adding another bird to your life list more than you’re willing to bear? Bee-ing might be right for you. As a birder, you already have all the skills you need, and with our new Bumble Bees of New England Guide, New England’s thirteen common bumble bee species are just waiting for you to add them to your new bumble bee life list.

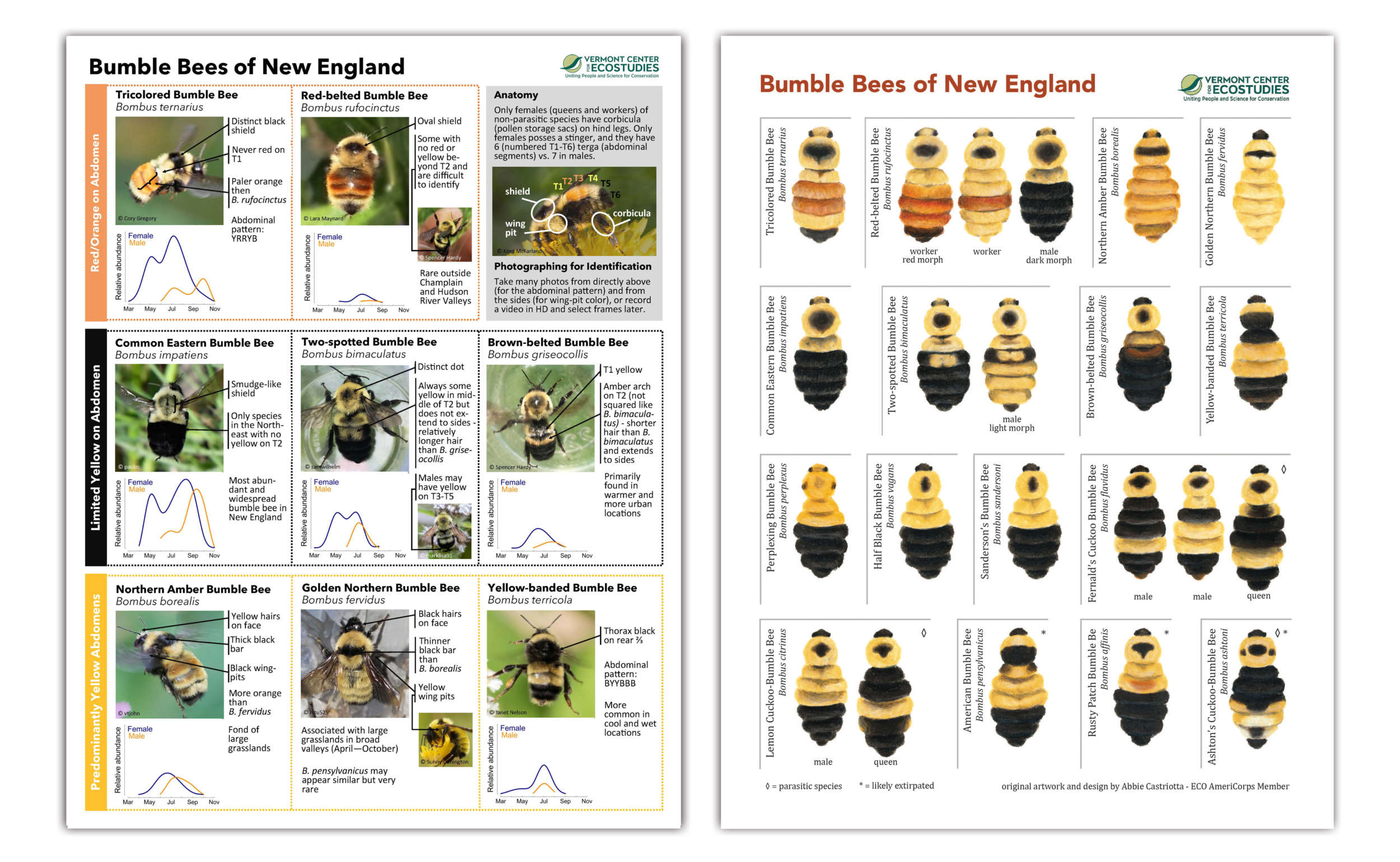

This free two-page pdf features annotated photos, defining field marks, and phenology graphs of the 16 bumble bee species in New England, as well as a few commonly confused look-alikes. An accompanying one-page illustrated plate is also available for download. You will soon be as proficient at identifying bumble bees by their field marks as you are with the thrushes and sparrows.

Spring and summer are a great time to start your new hobby. In spring, the mighty queen bumble bees are out foraging on spring ephemerals and searching for the perfect crevice for their new nest. Their large size and loud buzz make them hard to miss, and their consistent markings make them easier to identify. Bumble bee populations will multiply in the warmer months as the queen’s daughters take over foraging responsibilities for the colony. Homeowners participating in No-Mow-May and mowing less frequently throughout the summer are likely to see a few species of bumble bees right out their door.

Unlike birding, which often requires an expensive camera or impeccable binocular-phone coordination to get an identifiable bird photo, snapping a decent photo of a bumble bee with your phone is easy (we have some tips here). From there, you can upload your photos to iNaturalist or Bumble Bee Watch so that others can use your data for long-term monitoring of species’ ranges and phenologies. You can even add annotations—similar to breeding codes on eBird. Instead of noting that a bird is carrying food back to their nest as an indicator that they are feeding young, you can indicate when a bumble bee is carrying pollen to indicate that they have begun to raise offspring. Two VCE efforts are currently underway to mine community-generated bumble bee photos for data on flower preferences and timing of colony establishment. Robust monitoring efforts for bumble bees only began in 2012 with the first Vermont Bumble Bee Atlas, and there is still much for us to learn—your observations will help uncover the mysteries of the bumble bee world.

If you’re thinking, “well, there are only 16 species in Vermont and my Vermont bird list is over 200—how exciting can this really be?” just know that bumble bees are only a gateway genera. There are roughly 350 species of wild bees in Vermont of all shapes and colors. We are not asking you to drop your birding hobby, but consider turning your binoculars and camera towards the smaller bee-ings next time it gets hot and the warblers disappear deep into the forest. Let us know what you find on iNaturalist and Bumble Bee Watch!

—END—

Images Available for Use

Bumble Bees of New England Guides