Among the five loon species on Earth, none share as much habitat with people as does the Common Loon. As a result, no other loon species warrants more active protection.

Although they are iconic symbols of wild lakes and ponds, Common Loons, particularly in the United States, are vulnerable to nest disturbance and fishing practices. VCE's conservation strategy recognizes the need to help people and loons coexist.

Common Loons and Us

The loon nest is a simple pile of vegetation or a small depression in the soil, in which the female lays one or two eggs. Males and females both incubate the eggs for several hours before switching places. Once hatched, chicks under three weeks of age will often be seen “backriding” on an adult for warmth and protection from predators.

The loon nest is a simple pile of vegetation or a small depression in the soil, in which the female lays one or two eggs. Males and females both incubate the eggs for several hours before switching places. Once hatched, chicks under three weeks of age will often be seen “backriding” on an adult for warmth and protection from predators.

Loons nest only a foot or two from shore, making nests vulnerable to fluctuating water levels, particularly on reservoirs and lakes with dams. When waters rise, they can flood the nest. When a lake level drops, the adults, which can hardly walk on land, have a tough time sliding on their bellies to return to the nest.

It’s essential for people to keep respectful distance and enjoy loons through binoculars. When paddling a kayak or canoe, never pursue loons for a photo or a close look. Loons will leave their nest when people get too close, and may abandon the nest if disturbed repeatedly. Read more on our guide for boaters and landowners.

Feeding Loon Chicks

Male and female loons both tend to their young, feeding insects and minnows at first and larger fish later. Although loons will eat most any fish they catch, perch are a favorite food. A loon’s average dive length is 35-40 seconds. Most fish are swallowed underwater with only the occasional larger fish brought to the surface. In a loon’s gizzard, which contains small stones, powerful enzymes and stomach acids help to digest the fish – bones included.

Male and female loons both tend to their young, feeding insects and minnows at first and larger fish later. Although loons will eat most any fish they catch, perch are a favorite food. A loon’s average dive length is 35-40 seconds. Most fish are swallowed underwater with only the occasional larger fish brought to the surface. In a loon’s gizzard, which contains small stones, powerful enzymes and stomach acids help to digest the fish – bones included.

Common Loons will also eat live bait and lures from anglers. VCE routinely encounters loons tangled in fishing line, and loons that have ingested fishing line and bait. The results can often be fatal. Please reel in when loons are diving nearby and avoid using lead fishing gear of any kind. Read more on our guide for anglers.

Preening and Bathing

Loons preen their feathers constantly so that they remain waterproof. When the barbules of a feather are tightly locked, the entire feather sheds water, preventing the skin from becoming wet. Every few hours, a loon will roll over on its side to slide its bill through feathers, “zipping” them up. With its bill, a loon reaches back to a gland near their rear that produces an oily powder and spreads it on its feathers to help them shed water and hold their form. The tail feathers often stick straight up at this time, causing some people from a distance to think they are observing a chick backriding. At the end of preening, loons often flap their wings gently, shedding water and aligning their feathers.

Loons preen their feathers constantly so that they remain waterproof. When the barbules of a feather are tightly locked, the entire feather sheds water, preventing the skin from becoming wet. Every few hours, a loon will roll over on its side to slide its bill through feathers, “zipping” them up. With its bill, a loon reaches back to a gland near their rear that produces an oily powder and spreads it on its feathers to help them shed water and hold their form. The tail feathers often stick straight up at this time, causing some people from a distance to think they are observing a chick backriding. At the end of preening, loons often flap their wings gently, shedding water and aligning their feathers.

Occasionally a loon will bathe more vigorously, splashing its wings in the water, doing somersaults and plunge dives, and aggressively tending to its feathers with its bill. This behavior is often reported as a loon trying to remove tangled fishing line. But the loon is actually giving itself a thorough bath, trying to remove mites and other parasites. We’ve termed this process “extreme preening.” To a loon, it may feel good – like jumping into a lake on a really hot day. The loon usually finishes an extreme preening session with the more common gentle preening, re-oiling those feathers and zipping them up tight.

Loon Calls

- The Mournful “Wail” – An “ooohh ahhhh” is often the sounds of loons identifying or calling to each other; it can also signal initial signs of a mild disturbance.

- The Laughing “Tremolo” – A trill or series of trills can be a sign of distress or alarm, and occasionally excitement.

- The Crazy and Wild “Yodel” – This is the male territorial call, usually directed at unwelcome loons. Every male has a distinct yodel and transmits much information through the yodel – from how big the male is to his motivation to defend.

- Hoots and Coos – On a quiet evening you can hear the loon family or group of loons in a “social gathering” talking to each other.

Loons Through the Seasons

- April – Loons return soon after “ice-out” to our lakes and ponds to establish territories. Small ponds and lakes of less than 200 acres will have one loon pair, while larger lakes could have several. Intruder loons may target a territory for a “takeover” attempt, causing conflict amongst loons.

- May-June – Loons build their nests in a protected area, one to two feet from the water’s edge, often in a marsh or on a small island or one of our artificial nesting rafts. (Nests with water around them are much safer from predators such as raccoons.) The female then lays one or two eggs that will be incubated by both parents over 27 to 28 days. On average, loons do not nest until they are six years old.

- June-August – Adults guard their chicks during this period. Males might yodel at intruder loons or boaters who come too close. If intruder loons are present, chicks are often “stashed” near shore. The parents move the family to areas with less wind and wave action. Starting in mid-summer, you may observe larger groups of loons in social gatherings.

- September-November – The chicks become much more independent, learning to feed themselves and practicing flying for the upcoming migration. Adults undergo a partial molt in the late fall and will start looking like a big chick or a 1-to-2-year-old subadult (gray/white) with less pronounced white spots.

- November-April – Vermont loons migrate to their ocean wintering grounds off the New England coast. Upper Midwest loons head south to the Carolinas or the Gulf of Mexico. Adults have a complete molt in late winter, replacing their flight feathers, which means they have a flightless period before the spring migration.

Where to See Loons

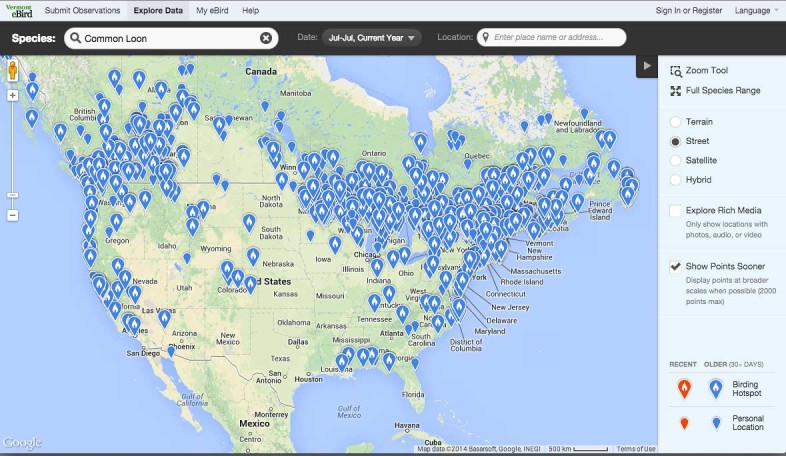

To find your local loons, consult this interactive map of Common Loon sightings in the current year from Vermont eBird, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life. Or click the map itself.