VCE biologists conducting vernal pool monitoring Photo by Emily Anderson

December can be a quiet time for career and community scientists who keep an eye on the status of northeastern wildlife. Butterflies have entered dormancy or exited the region. Loons have retreated to the Atlantic coast. And woodland pools that fill in autumn will remain silent until Wood Frogs return in spring. There’s no better time to reflect on VCE’s monitoring activities as we prepare for our winter bird counts. And it takes just a few numbers to get a sense of what’s been achieved.

- Loons breeding in Vermont surged to new records in 2024 with 85 successful nests producing 125 chicks.

- At 123, the number of nesting loon pairs represents an 18-fold increase over the low of seven in 1983. We found more new pairs nesting this summer (11) than were found statewide that year!

- Out in Vermont’s meadows, 1,250 community scientists submitted 11,872 butterfly observations through eButterfly and iNaturalist, including two firsts for the state: the Zabulon Skipper and the Sachem Skipper. All verified sightings will be incorporated into the Second Vermont Butterfly Atlas, now in its second of five years.

- Meanwhile, deep in forests, about 300 volunteers monitored thousands of mountain birds, interior forest birds, and pool-breeding amphibians to track their status.

- And the VCE science team returned to Mount Mansfield for the 33rd year to monitor rare and vulnerable birds, capturing 424 individuals representing 36 species, and affixing tiny radio transmitters to 19 female Bicknell’s Thrushes.

The extraordinary effort, concentrated in Vermont but spanning four states, strengthens our connection to the areas we study and inspires each of us to care for nature in ways that we can; but how else does monitoring contribute to conservation? We asked a few of VCE’s leading proponents of regular surveys, and they explained how long-term datasets contribute to every stage of the conservation process.

From the chair of the board’s science committee to the seasonal biologist who sets out nesting platforms for loons each spring, they see monitoring as an important tool for:

- understanding the status of species and habitats;

- detecting and evaluating environmental threats;

- steering limited resources toward areas of greatest need;

- informing the development and assessment of stewardship methods; and

- motivating people to protect and restore the health of ecosystems.

They also value monitoring as a tried and true source of questions and hypotheses for applied research.

Here is a sampling of individual perspectives on the importance of measuring change, shared by champions of monitoring who understand that persistence pays off.

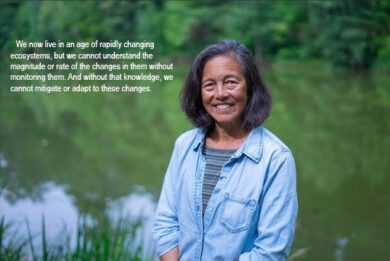

Celia Chen, Ph.D., is a Research Professor of Ecology, Evolution, Environment and Society at Dartmouth College. She joined the VCE Board of Directors in 2019 and has since chaired VCE’s Science and Conservation Committee. She has authored or co-authored over 100 publications about the bioaccumulation of mercury in aquatic food webs and related topics. She regularly shares the implications of her research with environmental managers as well as national and international regulators responsible for controlling mercury pollution. Photo by Chris Johnson

Celia Chen, Ph.D., current chair of VCE’s Science and Conservation Committee

I work in the area of mercury fate in the environment and it was because scientists were collecting data and noticing trends in mercury emissions, transport, and bioaccumulation that we now have an international treaty on mercury, the Minamata Convention. Without long-term data, we don’t know what human activities do to the environment. Moreover, once policy changes and regulations are implemented, monitoring data makes evaluating their effectiveness possible.

VCE is one of the few nonprofits collecting long-term data. As a society, we are not good at committing to collecting data on the same things over the long term. Government agencies do it sometimes but funding often goes away and the data collection ends. Academic scientists address scientific questions but few conduct monitoring. In some cases, visionary conservation organizations like VCE have stepped in to track important trends over time. VCE is unique in conducting rigorous science but also making the science accessible to the public and to policymakers. The organization is especially skilled in bringing science to communities and harnessing their interest and energy to support conservation.

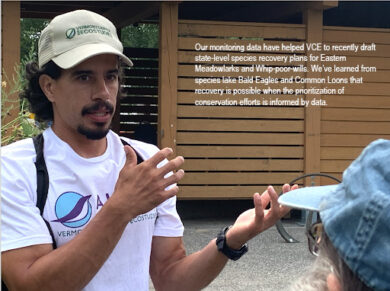

Ryan Rebozo, Ph.D., leads VCE’s team of conservation biologists as Director of Conservation Science, the same position he held at New Jersey’s Pinelands Preservation Alliance before moving to Vermont. His interests include disturbance ecology, plant-insect interactions, mycology, and rare plant demography.

Ryan Rebozo, Ph.D., Director of Conservation Science

Wildlife and plant populations are dynamic, changing through time in response to environmental conditions and stressors. Long-term monitoring can give us a better look at the trends behind these changes beyond stochastic events and can highlight threats to viability. Long-term datasets not only give us a better sense of past trends and current threats, but they also allow us to predict future changes with greater confidence than a more limited dataset would.

VCE’s dedicated scientists go beyond just delivering project data, we work to ensure our results are accessible to all and are used to inform conservation action. We do this by making all of our data openly accessible, creating data tools and visualization products that share our results with a wide audience, and actively participating in partnerships that promote science-based conservation.

William (Brian) Dade, Ph.D., is Emeritus Professor of Earth Sciences at Dartmouth College and the former chair of the VCE Science and Conservation Committee. He describes himself as a clear-eyed donor who appreciates that VCE scientists earn about $500 thousand each year from competitive grants and contracts that help validate their science. Photo courtesy of Brian Dade

William (Brian) Dade, Ph.D., Former Chair of the VCE Science and Conservation Committee

My background is in academic Earth Sciences and, though not an avid birder or ecologist, I readily understood the ways VCE benefits our community when I became aware of VCE’s aims and achievements after meeting Chris and Leslie Rimmer in the late 2000’s. One key dimension of VCE research is the maintenance of decades-long studies of the health and dynamics of, for example, mountain bird populations, loon populations, and vernal pool communities. Long-term studies focused on natural history have been neglected in academia for a long time, so I appreciate that VCE is monitoring indicator species that help us understand the changing world around us.

“Many conventional funding sources focus on shorter-term projects. As a result, long-term studies have largely been abandoned by many university departments. VCE is striving to fill a glaring gap in our approach to ecological studies.”

One reason that long-term studies have been neglected by many academics is the emergence and application of new technologies, such as genomics, which focuses on the study of the structure, function, geography and evolution of the genes of individual organisms and populations. That some VCE scientists have incorporated these state-of-the-art techniques in their studies speaks impressively to their efforts to remain intellectually relevant in exciting, ground-breaking ways. Most recently, for example, VCE scientists have participated in a study using artificial intelligence in image analysis in a monitoring project of nocturnal insects.

Brian and his wife Erika support VCE’s monitoring activities with their giving.

VCE’s outstanding efforts to involve community scientists in many studies raises our collective awareness of environmental challenges, while their outreach programs inform, engage, and inspire. These activities are dear to my heart and I am delighted to support them.

VCE is a Brave Little Organization befitting our Brave Little State. The dedicated scientists there strive to lead in ecological research and publication, scientific mentorship and community engagement, and thus affect how we, and our policymakers, view the natural world around us in important ways.

Eloise Girard, Seasonal Loon Biologist

Long-term monitoring of loon populations in Vermont has provided valuable data that directly inform environmental decisions. For example, monitoring efforts have revealed how loons are affected by ingestion of lead fishing tackle, and this understanding has led to statewide policies to reduce the use of lead tackle. It is now illegal to sell or fish with lead sinkers weighing ½ ounce or less in Vermont. This policy aims to decrease loon mortality rates and protect their populations by limiting exposure to toxic materials.

“VCE empowers individuals to take positive action and become part of solutions for environmental challenges.”

Eloise Girard has been working in the field of applied ecology for nearly 20 years on projects that span three continents. She joined VCE as a seasonal biologist on the Vermont Loon Conservation Project in 2021 and has helped Eric Hanson and their vast crew of volunteers keep up with the growing loon population since then. She has also taken part in community-based environmental projects alongside members of vulnerable groups such as new immigrants, people with special needs, and women with low incomes.

In 2013 and 2022, I participated in the Arctic Shorebird Demographic Network (ASDN), a long-term monitoring project dedicated to understanding shorebird population declines and the impacts of climate change. Established in 2009, ASDN is a collaboration of 17 organizations, including universities and government agencies, working across 16 camps in Alaska, Canada, and Russia. Being part of this network was a source of pride. I felt privileged to contribute to a project of this scale, where organizations unite to document shorebird trends and pinpoint the causes of decline.

VCE offers not only data and research to guide environmental stewardship but also opportunities to make meaningful contributions to ecological science. VCE empowers individuals to take positive action and become part of solutions for environmental challenges, helping people feel that they can make a real difference in a world that often feels uncertain. This ability allows people to connect with nature while fostering a sense of community, hope, and purpose. VCE’s work builds an informed, engaged community, reinforcing that every small action contributes to a larger, positive impact on the world around us.

—

What comes next for monitoring at VCE? Repetition, of course, except with more people fanning out across more of the planet throughout the year, equipped with new and increasingly powerful tools. This may sound like hyperbole, but consider that VCE scientists—pioneers of atlasing birds, butterflies, and bees—have recently helped launch: a multi-lingual eButterfly smartphone app, now being used in 43 countries across six continents; an international network of autonomous moth-monitoring stations; and a baseline assessment of how well Vermont’s conservation lands protect current and future populations of plants, animals, and fungi. And thanks to Conservation Biologist Kent McFarland, Data Scientist Mike Hallworth, and Software Developer Jason Loomis, these initiatives are integrated into the Vermont Atlas of Life, one of North America’s most advanced biodiversity monitoring platforms.

Our monitoring activities won’t always spur the dramatic recovery of an endangered and iconic wildlife population, as they have for Vermont’s loons; however, they will continually build the knowledge base that provides justification, focus, and technical guidance for sustaining healthy ecosystems wherever we work. And they will also stoke the enthusiasm and sense of community that conservationists need to succeed.

If you’ve taken part in monitoring biodiversity, what memories from the field stand out in your mind? What did you learn that you didn’t expect? And how do you hope your observations will be used to sustain healthy ecosystems? Please let us know in the comments below. And thank you!