Eastern Whip-poor-will / © Laura Gooch / CC 2.0

For more than a decade, VCE has led a project that takes place while most folks are fast asleep. Each summer, over two dozen adventurous Whip-poor-will Project volunteers venture into the darkness between sunset and sunrise to listen intently for the unmistakable call of the Eastern Whip-poor-will. Male Whip-poor-wills call on moonlit nights in early summer—and for many this song is becoming a nostalgic memory of the past.

Conducting nocturnal Whip-poor-will surveys is an activity sometimes prone to raise suspicion. While plying town roadways at night, I am often asked what I’m doing. Upon replying that I’m searching for Whip-poor-wills, and then asking if any have been heard nearby, the most common response is “I used to hear them, but haven’t in years.” Birders have made the same observation: Whip-poor-will numbers declined by 77% between the first (1976-1981) and second (2002-2007) Vermont Breeding Bird Atlas. What is causing this decline? There are several possible factors, including changes in habitat or depredation, but the decline of large moths, their primary food source, is also a strong possibility.

In response to recorded population declines in Vermont, the species was listed as state Threatened in 2011. In 2014, Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department partnered with VCE to design and conduct more intensive Whip-poor-will surveys to provide updated, accurate population estimates. The first year was a great success, as we found 74 males calling in the West Haven area. Since then, we have surveyed much of Vermont’s remaining low-elevation habitat, and found alarmingly few Whip-poor-wills.

This past field season, our target area was the Lake Memphremagog basin in North Central Vermont along the Canadian border. There are no historical records of Whip-poor-wills in Vermont eBird near Lake Memphremagog or its surrounding towns. John Buck, Vermont Fish & Wildlife’s Migratory Bird Biologist, and I weren’t sure if this was simply an under-birded area and Whip-poor-wills have been here all along, or if they were truly absent from the region.

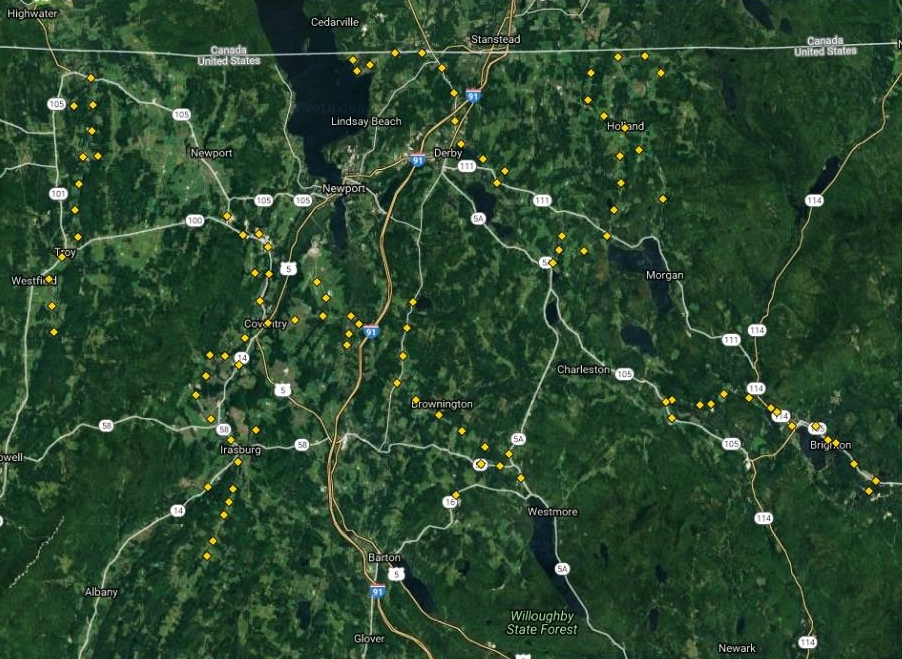

Kathy Wohlfort, a biologist who works with Audubon Vermont, and I set out to explore the Memphremagog area. We traveled roads running through quaint towns, rolling hills, quiet river valleys, and pristine dairy farms, with spruce forests scattered throughout much of the landscape. There was surely potential Whip habitat there: low-elevation river valleys lined with early successional habitat, a matrix of field and pine or spruce forests, and logging areas. We completed six roadside routes on clear, moonlit nights, from Troy eastward to Holland and south to Irasburg. We also surveyed ad hoc points outside each roadside route in areas with potential Whip-poor-will habitat (map below).

Additionally, we employed another set of “ears” along some routes: 10 Automated Recording Units (ARU), on loan from VCE’s Mount Mansfield Spring Phenology Project.

Automated Recording Unit placed at a survey site, set to record continuously from sunset to sunrise. / © Sarah Carline

Despite my enthusiasm to find at least one Whip-poor-will along our targeted survey area of 89 unique points, we detected none.

Luckily, 2018 didn’t completely lack Whips. After Kathy and I had surveyed the Holland Route for hours, Whip-poor-will-less, exhausted, and in need of a nap before sunrise surveys began, we set up camp at Brighton State Park, where the mosquitoes were swarming in thick, buzzing clouds. Bundled up in our sleeping bags, we heard loons calling on nearby Spectacle Pond, and then… a distant Whip-poor-will! With a limited number of clear, moonlit summer nights, we knew we couldn’t let this opportunity pass. Even though Brighton was east of our targeted area, we completed a few ad hoc surveys when time allowed, later finding a second Whip-poor-will a couple of miles away. We mapped a new route for Brighton, then set up the ARUs to serve as our ”ears” in Brighton while we continued with our primary standardized routes.

Sarah Carline on the shore of Brownington Pond at sunset, searching the map for additional ad hoc points to survey. / © Kathy Wohlfort

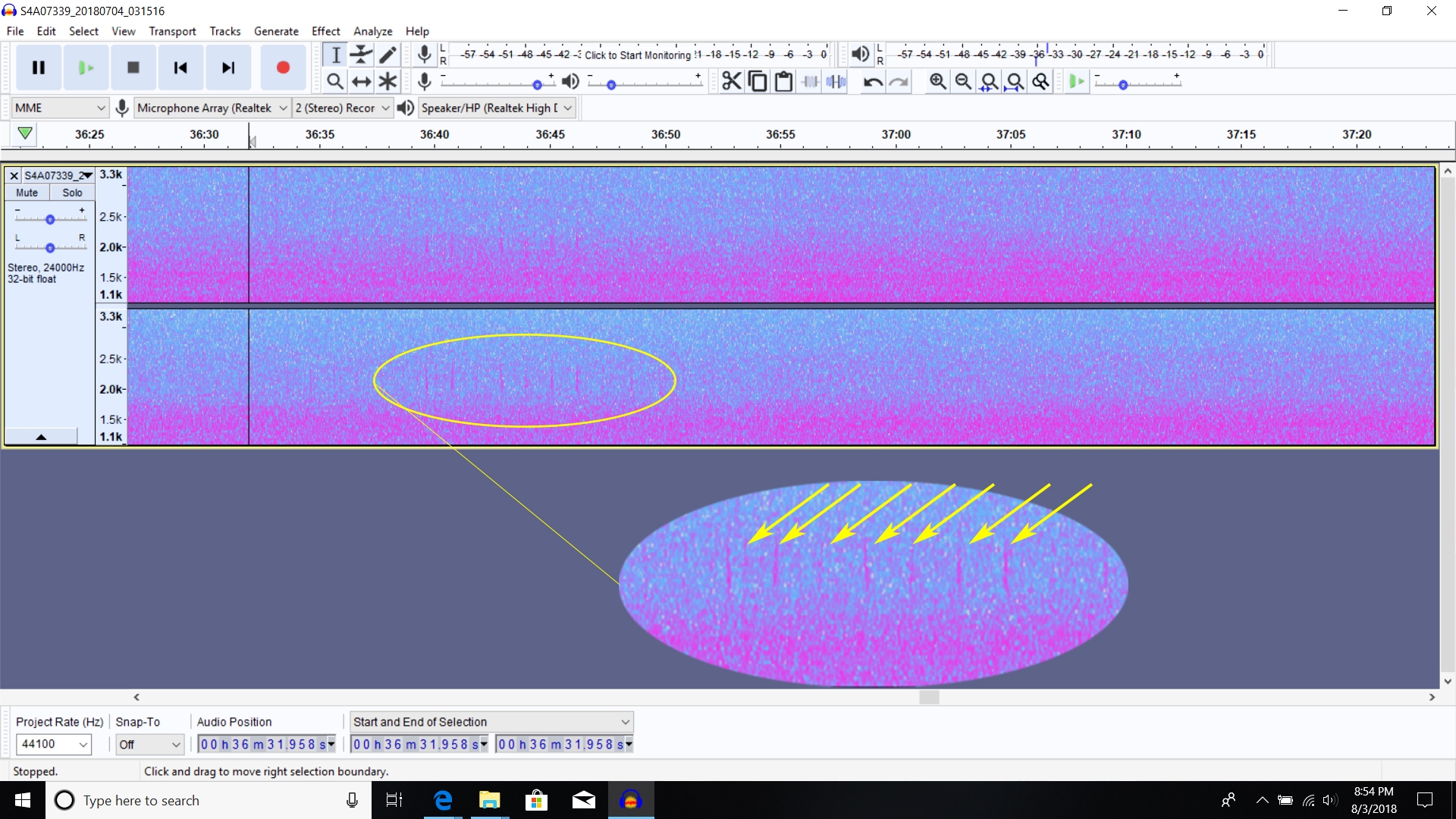

When our field season ended in early July, I started in on the next challenge: ARU data analysis. Most years, this is the period when I wrapped up volunteer data entry and began writing our annual report. But this year, I had the added task of processing an enormous amount of data—continuous recordings from sunrise to sunset for 22 points. Time allowed for analyzing only a small snippet of the entire set of recordings, so I put in my earbuds and listened to two hours for each point, while focusing my attention on the spectrogram:

The closely-spaced spikes indicate cadence, while line height shows the pitch of the male Whip-poor-will call.

I listened to peepers, peenting American Woodcocks, winnowing Snipes, hooting owls, and calling Black-billed Cuckoos. It was almost like being out in the field, and even those pesky mosquitoes showed up on the spectrogram. Many hours later, I heard a calling Whip-poor-will on a Brighton recording, which was barely recognizable on the spectrogram, proving our method of evaluation—both listening and viewing the spectrogram—to be a good choice.

We hope to again set up ARUs for VCE’s 2019 Whip-poor-will Project field season, and provide opportunities for volunteers to listen to (and watch) spectrogram recordings for Whips. If this sounds like fun, please contact me at . Or, If you’d like to help listen for these elusive birds in person, on moonlit Vermont nights, check out the map of routes to see if there is one you’d like to survey!

I live in southern NH. I’ve heard one Whip in the 43 years I’ve lived in this house. That was about 3 years ago and I think the bird was just passing through because we only heard it once. In 1958 we moved to Westmoreland NH form NJ. We bough a 45 acre side hill farm surrounded by county land and wood lots. Every night during the early summer we would heard 3 or 4 Whips calling. I moved away in Dec of ’68 so I don’t know if there are any still around. We also had a significant number of Partridge drumming and I can’t remember the last time around I heard one of those. I should note that I’m a Land Steward on a 1500 A conservation property I often visit to check trails in the earl evening and I’ve never head a Whip on that property.

While being helping out with a rattlesnake survey in southern NH, late May 2012, I found a whip-poor-will nest with 4 eggs not fifteen feet from a basking snake.

When I returned the following week, the eggs had hatched and tiny chicks stuck to the nest scape like glue. The female whip buzzed around our heads calling and then landed in front of us and, like a killdeer, feigned a broken wing.

In the late eighties and early nineties, we had several pairs of nesting whip-poor-wills in Blood Brook Valley, West Fairlee. My son and I turned on the porch light and chummed moths, which brought the whips in. After a few days, the whips would come in and wait for the light to go on; one often called from our roof.

Bryan Montgomery. 58, Tunnelton , Wv. 26444. I’ve heard whips here on my small farm where I grew up all my life. I’m listening to them right now. Never seen one in the wild. There very interesting.

I hadn’t heard a whippoorwill for years and to my surprise one night I heard one way off in a distance about six years ago since then I hear them every year and they are loud and clear just went out on my back porch tonight videoing them. It’s like music to my years.

Thanks, Daisy, for this valuable update. If this observation was in Vermont, you may have been the first person this year to record a calling whip-poor-will! Obtaining more information about whip-poor-will’s arrival dates to their breeding grounds is important information. We’d really appreciate it if you entered this into eBird.org. You can read a quick tutorial if you aren’t familiar with eBird yet, and you can even enter the audio from your recording. So far, there is only one whip-poor-will recording documented in 2021, on April 24 near Snake Mountain in Addison County. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to email me at . Happy listening to their energetic calling this summer!

Are there whippoorwills in the Catskill Mts. in NYS? Are they only visible at night?