The 2020 State of the Mountains Bird Report has landed… on the web. In this evolving report, we try to answer one seemingly simple question: What is the state of the mountain bird species of the northeastern United States? Using long-term data collected by citizen scientists working on VCE’s Mountain Birdwatch project, we’ve created population health indicators for each species that reveal which species are thriving and which need attention. We seek to understand where our conservation efforts have succeeded and where they have not: and where we have fallen short in our efforts to protect the birds of our mountains, we offer insights and suggest solutions.

The 2020 State of the Mountains Bird Report has landed… on the web. In this evolving report, we try to answer one seemingly simple question: What is the state of the mountain bird species of the northeastern United States? Using long-term data collected by citizen scientists working on VCE’s Mountain Birdwatch project, we’ve created population health indicators for each species that reveal which species are thriving and which need attention. We seek to understand where our conservation efforts have succeeded and where they have not: and where we have fallen short in our efforts to protect the birds of our mountains, we offer insights and suggest solutions.

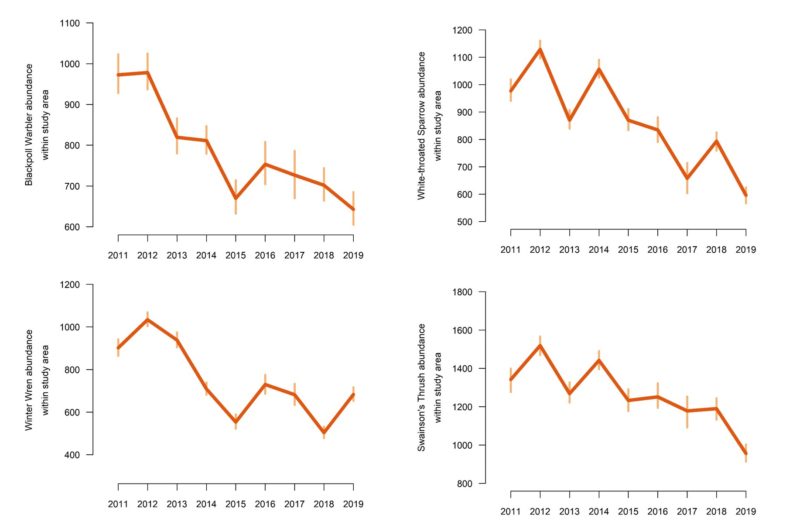

To summarize, the 2020 State of the Mountains Bird Report indicates steep and consistent declines for at least half of the 10 bird species monitored through Mountain Birdwatch. For example, our high-elevation populations of Blackpoll Warbler and White-throated Sparrow have both likely declined by >34% since 2011. These populations have been declining in all four states that comprise the Mountain Birdwatch program: New York (Adirondacks and the Catskills), Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. White-throated Sparrows are short-distant migrants, commonly found at backyard bird feeders in New England during winter. Blackpoll Warblers, on the other hand, undertake long-distance migrations to South America, requiring 2-3 days of non-stop flight down the Atlantic coast with stopovers in the Caribbean.

Of the 10 bird species monitored by Mountain Birdwatch citizen scientists, five have experienced steady and substantial declines from 2011 through 2019 in the northeastern United States, including Blackpoll Warbler (upper left), Winter Wren (lower left), White-throated Sparrow (upper right), and Swainson’s Thrush (lower right). Panels show the local abundance estimates (thick orange lines) of these four species each year around the ~750 Mountain Birdwatch sampling stations. Vertical orange lines present the 95% Bayesian credible interval – a measure of uncertainty surrounding the annual population estimates.

So, what do these two species have in common? Their populations are concentrated at high elevations (>1100 meters or >3609 feet) in the mountains of the Northeast during breeding season, and they are both highly susceptible to the effects of global climate change. As temperatures rise over the next 100 years, both species are predicted to shift their breeding ranges northward. By 2120, it’s likely that the breeding ranges of Blackpoll Warblers and White-throated Sparrows will be entirely restricted to the boreal forests of Canada and Alaska. Unfortunately, similar climate modeling also suggests the same pattern for the other declining species in the State of the Mountain Birds Report: Winter Wren, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, and Swainson’s Thrush.

Given these forecasted changes, it is imperative that we continue to monitor these species through Mountain Birdwatch and document their responses to climate change and other human-induced planetary changes like habitat loss and degradation. VCE’s scientists, along with researchers across the continent, are racing to find ways to slow and reverse these declining trends and northward shifts through such actions as habitat modification and (potentially) through reintroductions, translocation, and assisted migration. Thanks to the annual baseline data provided by Mountain Birdwatch, we’ll be in a strong position to fully understand how (or if) various management actions positively benefit these avian populations.

COVID-19 has certainly thrown a wrench in our plan for 2020 Mountain Birdwatch surveys, but we are hopeful that some citizen scientists will be able to monitor their routes this June. For example, many of our Mountain Birdwatch routes in Maine occur on remote private property where one rarely encounters another person. While we continue to assess the situation, interested hikers who enjoy birds (or birders who like to hike) can interact with a map of unadopted routes on our website. If you’re interested in conducting Mountain Birdwatch surveys on one day in June, please contact me. We also welcome your feedback on the State of the Mountain Birds Report. Is there additional information you’d like to see? How else might we display the data to make the report more engaging (e.g., interactive figures)? Drop us a line, and keep an eye on the State of the Mountain Birds Report website for updates.

We have noticed winter wren nesting in our yard has increased over the last few years. Could they be changing habitat or breeding locations as they adapt?

Hi Sandy,

That’s entirely possible–on a local (i.e., backyard) level it is very difficult to say if the increase in wrens is due to just normal fluctuation in local population size or some evolutionary adaptive behavioral response. Those kinds of questions are best answered from looking at landscape-level data. Speaking of which, our colleagues at Audubon published the results of some climate modeling, and here’s the report for Winter Wren (https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/winter-wren#bird-climate-vulnerability). As you can see, even under moderate increases in temperature over the next 100 years, Winter Wrens are all but likely to disappear from the United States (as a breeding species) as their breeding range shifts northward further into Canada.