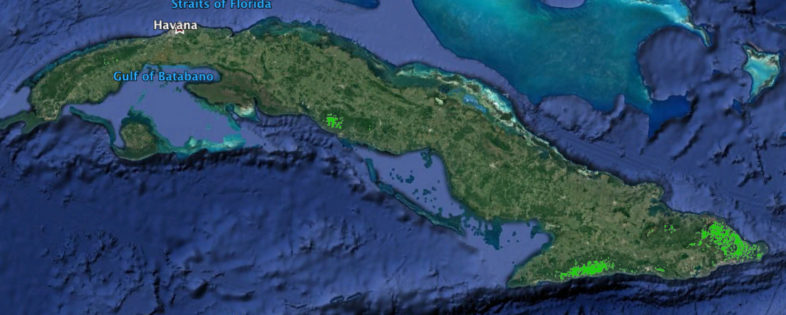

Sierra Maestra, eastern Cuba, the only known region (so far) of Bicknell’s Thrush occurrence on the island. Photo by Óðinn CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The wait is over. Our visas materialized. Flights are booked, gear packed. Cuba beckons. John Lloyd and I leave early tomorrow for a long-awaited exploratory trip to the island’s eastern tip. Our quest? Bicknell’s Thrush, of course. With colleagues from the Cuban institute Centro Oriental de Ecosistemas y Biodiversidad (BIOECO), headquartered in historic Santiago de Cuba, we’ll launch islandwide surveys for this vulnerable migrant that has featured so prominently in VCE’s plans for so long.

We’ve known for years that Hispaniola is the epicenter for overwintering Bicknell’s Thrush. We estimate that 80 to 90% of the songbird’s global population packs itself into the island’s dwindling broadleaf forests for six to seven months each winter. However, recent computer modeling by VCE Conservation Biologist Kent McFarland has us rethinking Cuba’s potential for Bicknell’s Thrush wintering habitat. With the model as our guide, and funding from the Canadian Wildlife Service through our longtime colleague Yves Aubry, VCE is poised to tackle Bicknell’s Thrush on Cuba. It won’t be easy—it never has been—but we don’t call ourselves ‘brute force biologists’ for nothing.

Modeled Bicknell’s Thrush habitat (bright green) on Cuba, from McFarland et al. (2013). VCE’s upcoming field expedition will target the island’s two largest blocks in the Southeast: Sierra Maestra (westernmost) and Humboldt National Park (easternmost). Click on the map to learn more about this model.

We know Bicknell’s Thrush occur on Cuba. Yves and associates found >20 birds in the rugged Sierra Maestra (Fidel Castro’s infamous pre-revolutionary refuge) during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Our goal for this expedition is to revisit some of those high-elevation sites via a backpacking trip to the remote cloud forests, then to venture eastward to the wet serpentine broadleaf forests of Humboldt National Park. Of course, we hope to find thrushes in both areas, perhaps even to mist net a few individuals, but our main goal is to introduce our BIOECO partners to the trials and tribulations of Bicknell’s Thrush field surveys. We hope they’ll take on the bulk of islandwide surveys next winter, and beyond if needed.

Bicknell’s Thrush in a tree fern, Sierra de Bahoruco cloud forest, Dominican Republic. This habitat is very similar to what we expect to find in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra. Photo courtesy of Pedro Genaro.

Like Hispaniola, Cuba supports high levels of endemism, with no fewer than 26 endemic birds. Sadly, 22 of these are of national and international conservation concern, due to habitat loss from many of the same threats facing Hispaniola’s avifauna. For overwintering Bicknell’s Thrush, our model tells us that 15% (5,003 km2) of potentially suitable habitat rangewide exists in Cuba; most of this is within Sierra Maestra and Humboldt National Park. I’m going to make a rash prediction here and forecast that Cuba supports an overwintering population second only to Hispaniola’s, though in far fewer numbers and locations. Vamos a ver!

We have little idea what to expect from our upcoming trip, other than the inevitable surprises that Bicknell’s Thrush (and Cuba itself) will surely provide. Regardless of our findings, we’ll take the first steps in obtaining crucial information to prioritize and direct both local and rangewide conservation planning for this species’ vulnerable winter habitats. And, we expect to return with memorable stories of Cuban birds, people, and landscapes. Me? I can’t to see and hear my first Cuban Solitaire.

Cuban Solitaire, an endemic on VCE’s radar for our upcoming expedition to Sierra Maestra and Humboldt National Park. Photograph by Allan Hopkins (CC BY-NC-ND-2.0)

Chris, An inspired idea! So pleased you’re getting to take this trip.

Via con dios y aves.

Anxious to hear what you discover!

Buen Viaje Chris y John

I am sure with BIOECO you will have a great exploratory field trip in the Eastern mountains of Cuba. Hope VCE and BIOECO can consolidate future research and conservation projects in Eastern Cuba for Bicknell’s Thrush conservation and Cuban bird and biodiversity conservation.

Glad you are finally getting to make this happen Chris. Bon voyage and safe travels.

Adventure Scientists! Oh to be a badass biologist like you guys.