Evolution in Spatial Tracking of Bicknell’s Thrush

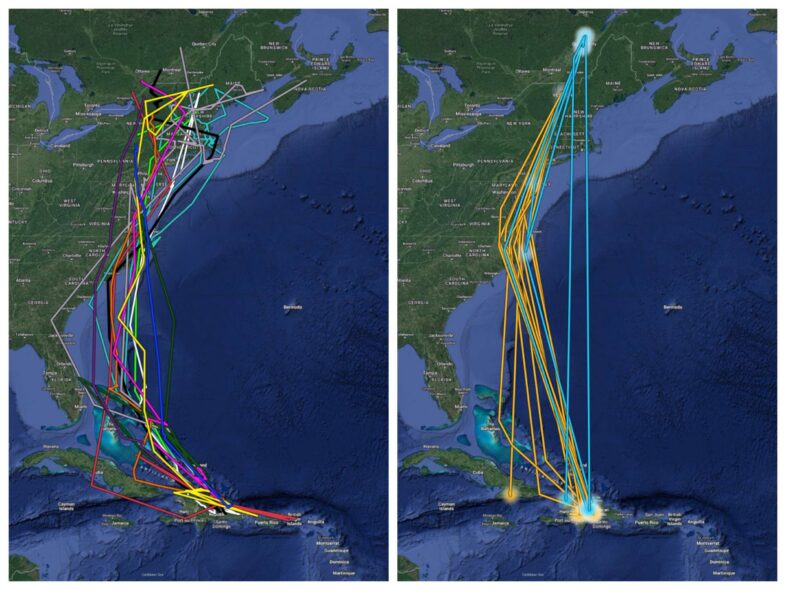

Comparison of Bicknell’s Thrush southward migration data from light-level geolocators (left) and GPS tags (right, orange lines are from Mt. Mansfield, blue from Quebec). Light-level geolocators provide more data points with lower accuracy, and show the majority of birds migrating through or over the Bahamas. GPS tags collect fewer data points and rarely captured any stopover locations in the Caribbean, but yielded very precise overwinter locations.

In VCE’s 30+ years of Bicknell’s Thrush (BITH) research, we’ve used many different methods to unlock the species’ ecological secrets. We’re talking tissue samples, nest cameras, and a myriad of tracking technologies–we’ve done it all! Many of you have been following our current groundbreaking GPS tracking study, but did you know that this isn’t our first time deploying tracking units on BITH?

Bicknell’s Thrush wearing a light-level geolocator (left, © K.P. McFarland) and GPS tracker (right, © Kevin Tolan)

Our tracking efforts began with radio telemetry back in the 1990s, on Mt. Mansfield and Stratton Mountain, and then in cloud and rain forests of the Dominican Republic. Telemetry uses radio signals, in the form of electromagnetic waves, to determine an animal’s location. This method is only useful when the subject and observer are close enough to each other to pick up signals on a portable antenna, but an individual’s movements can be tracked for a period of up to 3-4 weeks. We have gained tremendous insights on BITH using radio telemetry. The list includes, but is not limited to: the unique mating system of BITH, the fact that breeding males occupy large home ranges instead of discrete territories, and that birds of all ages and sexes are in fact territorial on their wintering grounds. Telemetry also made it possible to find many BITH nests, a near-impossible task otherwise, by tracking females. However, we were still left with many important questions about the species’ migratory patterns and ecology.

Enter a world of new tracking technology. Between 2009 and 2011, VCE and our partners deployed light-level geolocators in New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Quebec to document the migration routes and timing of BITH. Geolocators, also known as geologgers, track the cycle of daylight, using daily timing of sunrise and sunset to extrapolate an approximate position.

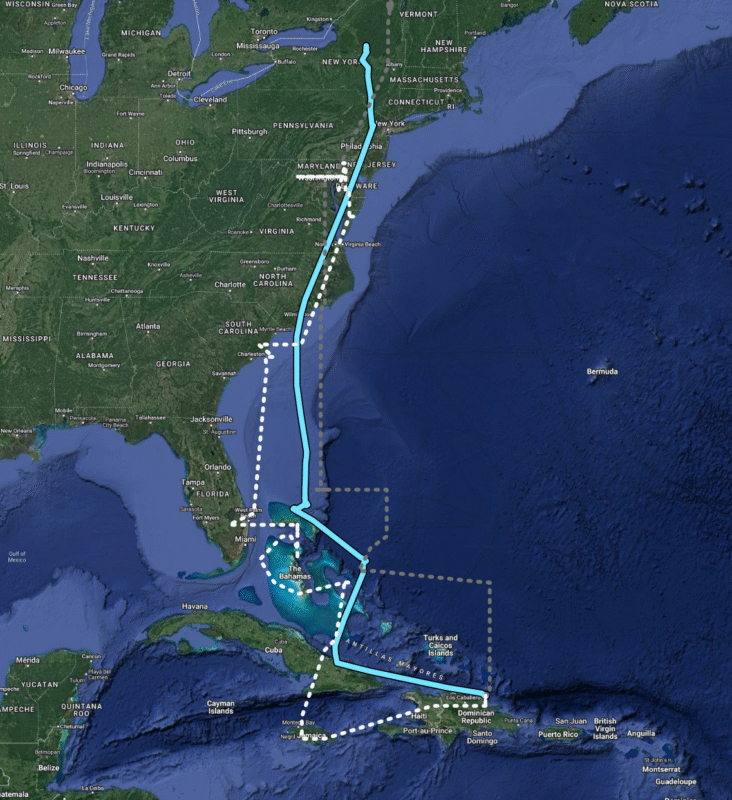

Geolocator #7556’s southbound migration showing the upper (gray) and lower (white) boundaries of the geolocator location data, with an averaged midline (light blue).

Our study using geolocators gave us important data regarding the migration routes and timing that BITH follow. Because data are collected using only a light sensor and tiny computer, geolocator battery life lasts a full year. This makes the devices excellent for tracking large-scale movements, such as annual migrations. They’re also quite a bit smaller than GPS tags, which until recently, weren’t miniaturized enough to deploy on BITH.

One major drawback is that geolocators don’t have a high level of accuracy (+/- 200 km in either direction). As such, they can’t give precise locations or track small-scale movements. For example, they’re useless when studying overwintering sites, or the intratropical movements that we’re now investigating in BITH.

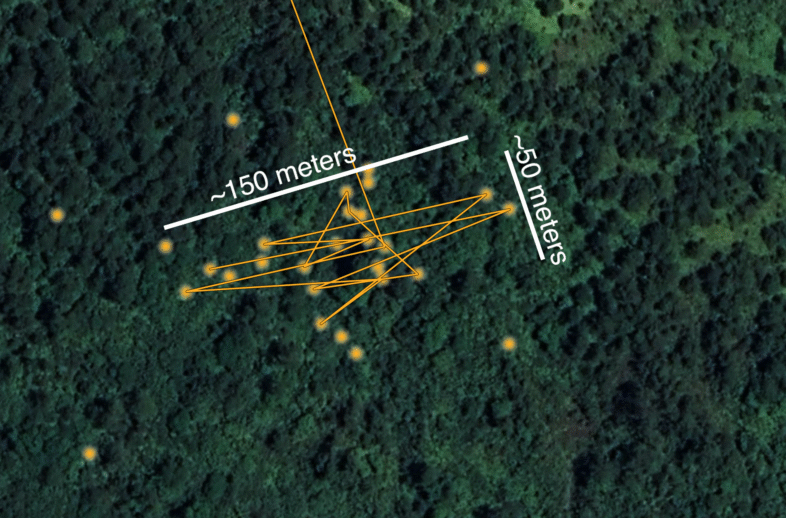

Bicknell’s Thrush 2821-79262 spent most of its winter within a 3 acre area in central Dominican Republic.

Using new GPS technology is the next step in furthering our understanding of BITH full life cycle ecology, which has long puzzled us and other avian conservationists.

The GPS trackers we’re now using have a shorter battery life than geolocators, but they allow us to track birds on a much smaller, more precise scale. With a range of error as little as 5 meters, we can uncover fine-scale movements that would previously have been unmeasurable. And, although we don’t gain as much data this way, the spatial resolution of GPS trackers yields unprecedented insights.

These two technologies, light-level geolocators and GPS tags, complement each other’s strengths. Geolocators showed that the majority of southward-bound BITH tend to “jump off” from the Carolinas and pass down through the Bahamas en route to Hispaniola. The 16 GPS units we’ve retrieved thus far (12 on Mansfield, 4 in Quebec) have shown us definitively and precisely where individual BITH spend their winters, and when/where they move off territory. Together, these two methods provide unprecedented insights into the annual movements of BITH. As we (hopefully) retrieve additional GPS tags in the weeks ahead and into next summer, our knowledge will become more and more robust. There are sure to be surprises, so stay tuned for more updates in the near future!