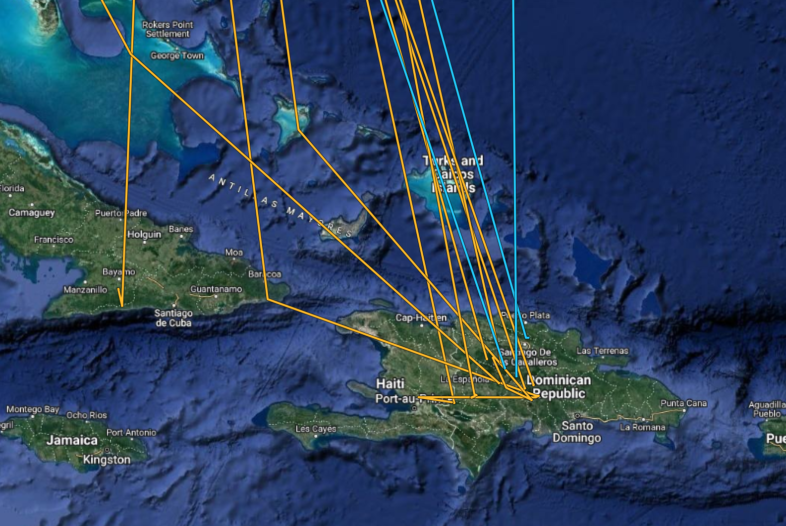

GPS tracks of 13 male Bicknell’s Thrushes tagged during the breeding season of 2021. Orange lines represent Mt. Mansfield birds, blue lines BITH tagged in Quebec. All but one bird overwintered in the Dominican Republic, while one individual made its winter home in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra. Note that the lines approximate actual migratory pathways.

Backpack-toting Bicknell’s Thrushes (BITH) are proving their mettle, and then some. After our exhilarating recovery of 5 GPS tags from male BITH on Mt. Mansfield two weeks ago, VCE was elated to retrieve another 5 units on 14-15 June. And, Quebec has now joined the fray, as our longtime Canadian Wildlife Service colleague Yves Aubry recovered 7 of the 14 tags he affixed to male BITH last June. We’re gaining truly invaluable insights, even if no truly astonishing discoveries have yet surfaced.

In a nutshell, our cursory look at the data contained within these GPS tags (each of which has yielded 40-55 spatially precise “fixes”) shows that 12 of 13 BITH spent the main part of winter in the Dominican Republic (DR), with one male hunkering down in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra. That confirms (for now) what we have long suspected, based on field evidence—that up to 90% of the global BITH population overwinters on Hispaniola, with the great majority of birds confined to the DR. Most of these appear to inhabit cloud forest sites in the island’s most extensive mountain range, Cordillera Central. Surprisingly, we have yet to document a BITH overwintering in Sierra de Bahoruco of the southwest DR, and only one bird in Cordillera Septentrional along the north coast. However, with additional tags surely to come, and a more thorough examination of all data, the full story is far from told.

Approximate midwinter locations of 13 GPS-tagged BITH from Vermont (10) and Quebec (3). Most birds settled in the Cordillera Central, Hispaniola’s most extensive region of high-elevation forest.

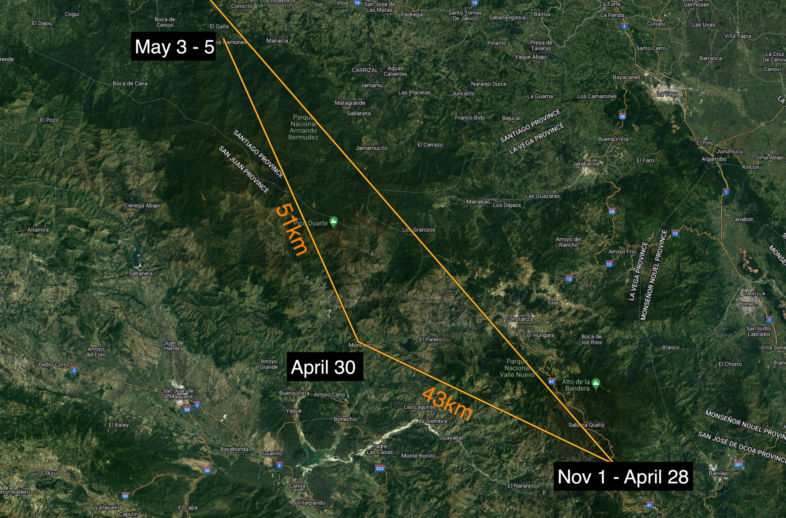

One Mansfield bird recovered this week showed some intriguing late-season dispersal, moving 43 km northwest on April 28-29 from a cloud forest site in Parque Nacional Valle Nuevo, and another 51 km only 2-3 days later to a high-elevation forest patch in Parque Nacional Armando Bermudez, where its GPS battery died. Given the late dates, it’s tempting to speculate that these were pre-migratory movements towards a northward launching point, but we’ll never know for sure.

Late-season movements of BITH #2821-79238, a yearling male, from his stationary territory in Cordillera Central cloud forest to another high-elevation forest tract ~90 km northwest. Unfortunately, the bird’s GPS battery died on 5 or 6 May.

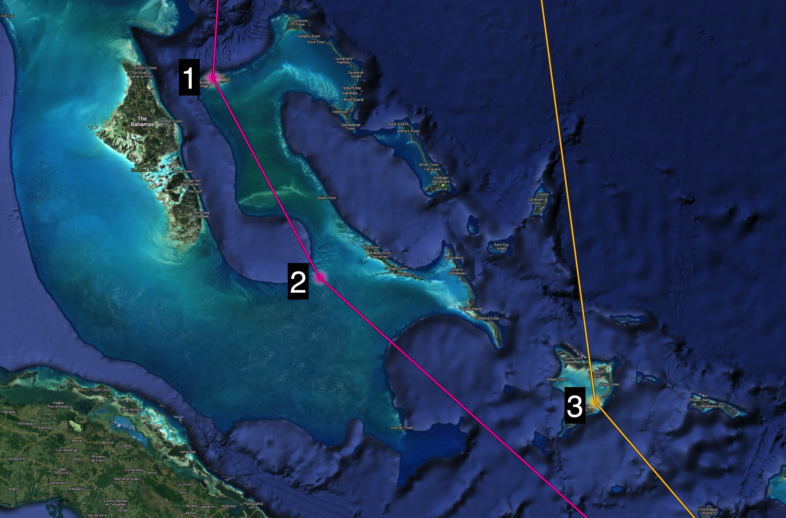

One additional highlight for now from the new crop of GPS tag data, which we have only cursorily examined: two BITH made landfall in the Bahamas before continuing to their overwinter destinations in the DR. One bird was on New Providence Island on 15 November, then provided a GPS fix 15 days later during its apparent nocturnal migratory flight southward, as it appeared over open water ~65 km west of Great Exuma (fixes are scheduled at midnight, so it had to have been flying). A second bird was on Acklins on the early date of 15 October. Because GPS battery life limits the number of fixes we can schedule in each backpack, and since our primary research question involves late winter movements of BITH, we scheduled only 3 monthly fixes in September—November, concentrating fixes in March and April. Thus, any data obtained during fall migration are essentially “gravy” for us, though fascinating and informative. We now know what we have long suspected; that the Bahamas are a stopping point for at least some migrant BITH in autumn.

Fall migration GPS locations of two male Bicknell’s Thrushes in the Bahamas. One bird (pink) was on New Providence Island on 15 November [1], then was recorded over open ocean in an apparent migratory flight on 30 November [2]. A second bird (orange) made landfall on Acklins [3], where it was recorded on 15 October, before continuing on to the DR.

Swainson’s Thrush — 5 new bandings; 4 males, 1 female with full incubation patch

Purple Finch — 3 (1 male, 2 females with brood patches)

Pine Siskin — 1 female with regressing brood patch

Dark-eyed Junco (Slate-colored) — 8 (5 males, 3 females with incubation/brood patches)

White-throated Sparrow — 8 (7 males, 1 female with incubation/brood patch)

Magnolia Warbler — 2 yearling males

Blackpoll Warbler — 15 (11 males, 4 females); 8 new bandings, 4 returns (female from 2019, 3 males from 2021), 4 within-season recaptures; females with incubation patches

Yellow-rumped Warbler (Myrtle) — 7 males: 1 new, 1 return from 2019 and 2 from 2021, 3 within-season recaptures

Black-throated Green Warbler — 1 female with full incubation/brood patch; this may now be a locally-breeding species

VCE’s champion all-time Mansfield data recorder Dory Hindinger exercising her immaculate penmanship (left) and releasing a banded female Purple Finch (right). © Michael Sargent (left), Charles Gangas (right)

We’ll be back at it next week, the following week, and every week through early August, as we continue season #31 of avian monitoring on Mansfield. To say the least, this year’s dimension of BITH GPS tag recovery adds an invigorating element of intrigue and discovery. We have yet to recover a 2021-tagged female, but I’m confident we will. Above all, we are humbled to contemplate that these diminutive 1-ounce songbirds have survived—toting miniaturized backpacks, no less—an arduous annual cycle that encompasses nesting, annual molt, fall migration, overwintering 1500-2000 km away, and a return northward flight. Whew!

Wow this is fascinating info! Thanks for telling us about the great successes in GPS tracking.

Amazing! Thank you.

This article might be of interest. hope all’s well. Happy fathers day! yo

Interesting that Bicknell’s Thrushes seem to prefer to overwinter in the Dominican Republic verses Haiti. I am sure it has to do with more protected habitat in the D R. Keep up the good work!

Great Post, Chris. Thanks much

Really enjoyed the post. Wonder how many readers might know what a brood patch is? Perhaps explain the significance?

You said it all – ‘intrigue and discovery’. They will draw you back for a loooog time to the stories the Bicknell’s have yet to tell. Thanks for the update.

Very interesting report! It is amazing that a one once bird can travel non-stop over the oceans multiple times over their lifespan.

I do have a couple of questions. Do you have any recent data about BITH overwintering in the Cordillera Central in Puerto Rico? Do the geo tags record air temperature and altitude? Thank you!

With apologies for such a belated response, it is indeed amazing that a tiny songbird can make such an arduous and perilous migratory flight year after year. We’ve had at least three 10 year-old BITH over the years, and that is truly an extraordinary accomplishment.

As far as BITH overwintering in Puerto Rico, we do have some fairly recent data that show the species to be common but fairly rare overall on the island. Most records (VCE’s and others’) have been from Cordillera Central. Looking at eBird, I don’t see any records from this past winter, but our colleague Julio Salgado found 4 birds on Cerro Jayuya on 9 Feb 2022. Julio is the #2 all-time birder (according to # of species in eBird) on the island, and he’s barely 30 years old!

We also found BITH in Puerto Rico during our islandwide surveys in 2015 and 2016. If you’re interested, we published a paper on our findings in the Journal of Caribbean Ornithology in 2019: https://jco.birdscaribbean.org/index.php/jco/article/view/934

Thanks for your interest, Fernando!