Although the days are slowly growing longer, life in the Northeast now finds itself in the coldest depths of winter. January is about survival. Wildlife that doesn’t migrate adapts instead in order to make it to spring. Here’s a few tidbits of natural history happening outdoors this month around you.

THE EAGLES HAVE LANDED

Bald Eagle populations have been slowly rising for decades in the Northeast. Winter provides a great opportunity to see these majestic birds as the congregate around areas of open water on lakes and rivers where food is likely to be found.

Well-known places in Vermont to see eagles include: below the Wilder Dam in Hartford or along the edge of ice on Lake Champlain, specifically near Chimney Point Bridge and Fort Cassin Point near Ferrisburgh. Your best source of recent sightings is on Vermont eBird. Check out the live map of Bald Eagle reports for the whole region and plan your trip.

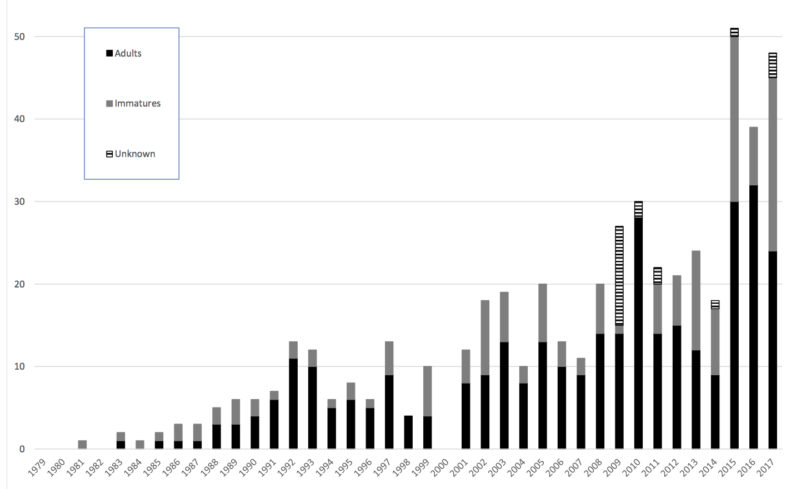

The nationwide Mid-winter Eagle Survey takes place from Jan 3-17 this year and is coordinated by Vermont Audubon in Vermont (learn more). Since 1979, volunteers have been counting wintering Bald Eagles in early January on non-overlapping standard routes in 43 states, most of which have seen steadily increasing populations since the count began.

Vermont has 15 standard survey routes, and also covers several additional Bald Eagle “hotspots” throughout the state. Last year’s count tallied a total of 48 eagles on the standard routes, and volunteers and members of the public counted an additional 37 eagles in other parts of Vermont. The numbers of eagles counted each year varies due to several factors, including survey conditions and the amount of ice on the waterways. More ice usually means the eagles are concentrated in areas of open water so they can hunt fish and waterfowl.

Don’t forget to add your sightings to Vermont eBird and include important information you witness such as approximate age and any notable behaviors (i.e., carrying nesting material, flying with another eagle, etc.).

RUFFED GROUSE ARE DOWN UNDER

Where’s the warmest place for a bird to spend the night? Depending on the temperature, it might be subnivean. WIth the air temperature dropping well below freezing, a deep blanket of snow might be the insulation that separates life from freezing death for a Ruffed Grouse. You can find places they’ve roosted by the marks in the snow showing where they entered and where they exited their winter den. They may even burst out of the snow in front of you, frightening you into a warmer state. On a warmer night or when snow conditions are poor, grouse may settle for roosting in the branches of an evergreen tree.

Each fall Ruffed Grouse grow comb-like rows of bristles (called pectinations) on their feet. These create a “snowshoe” effect for the grouse, allowing them to walk on the surface of the snow. Grouse also have extra feathers that cover the nostrils on the beak to make the air just slightly warmer as it enters their airways, like a balaclava mask you might wear on a cold winter day.

SNOWBIRD SOCIAL LIFE AT YOUR BIRD FEEDER

This year seems to be a record year for Dark-eyed Juncos, also known as ‘snowbirds’, around bird feeders here in Vermont. And if you watch them carefully at your feeder, you might notice something about these winter flocks.

Each flock has a dominance hierarchy with adult males at the top, followed by juvenile males, and females at the bottom. Watch them at your feeders and you can often observe individuals challenging the status of others with aggressive displays of lunges and tail flicking. But the farther north you are, the fewer females you will see in the flock. To avoid competition, many females migrate farther south than most of the males. Up to 70% of Juncos wintering in the southern U.S. are females. Males tend to stay farther north in order to shorten their spring migration and perhaps gain the advantage of arriving first at prime breeding territories.

Want to learn the ins and outs of aging and sexing Dark-eyed Juncos by plumage? Check this awesome resource out.

MYTH BUSTER: THE FABLED JANUARY THAW

Let face it. We could all use one this year. The cold snap we’ve been enduring has been enough. But will we get one this year? Is it really a thing?

In much of the Northern Hemisphere the coldest day of the year, on average, falls on January 23. During the final week of January, temperatures are thought to show a slight increase, and subsequent dip. The ‘January thaw’, as it has been named, is said to last for about a week. Researchers from Cornell University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration aimed to find out if this piece of meteorological folklore was fact or fiction. Their analysis published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society in 2002 concluded that “the effects of sampling in finite climate records are wholly adequate to account for the existence of January thaw “features” in northeastern U.S. temperature data.” They also state, “While this powerful human capacity to find order in nature has served and continues to serve us extremely well, it also sometimes leads us to falsely impute meaning to chance events.” In other words, it’s all in our heads. There is no January thaw in the records according to their analysis.

BLACK BEARs give BIRTH

By now bears are ensconced in their winter dens, slowly burning the thick layers of autumn fat. January’s full moon is sometimes called the ‘bear moon’. Later this month and into early February, the females will give birth.The mother bear will lick them clean, keep them warm, and move into a position that makes it easier for them to nurse. The newborn cubs weigh about same as a can of soda. They’ll nurse on their mother’s high-fat milk and by spring they will be 6 to 8 pounds.

Deer yards are key to winter survival

White-tailed Deer survive the harsh northern winters using specific winter habitat, what most of us call “deeryards.” These areas have ample evergreen trees for cover on slopes that often have a southerly aspect, providing protection from deep snow, cold temperatures, and wind. Deeryards might be only a few acres to perhaps as large as 100 acres. If conditions remain the same, these yards can be used for generations. Deer may migrate from miles around in late fall to use these areas for the winter. The deer cut their metabolism in half during this time of scarcity in an effort to make it until the lush grasses of spring arrive.

Deeryards are also important for a variety of other wildlife: porcupines, snowshoe hare, fox, fisher, coyotes, bobcats, crows, ravens, crossbills, owls and more. Human encroachment or forestry operations can have a devastating effect on these stands and the wildlife that rely on them. Deeryards make up a small percentage of the land. Only 8% of the forested landscape of Vermont has been identified as deeryard.

Listen to Outdoor Radio as they visit a deeryard and talk more about these important habitats.

“Who” Will Lay The First Eggs of 2017?

Listen for Great Horned Owls advertising their territories with deep, soft hoots in a stuttering rhythm: hoo-h’HOO-hoo-hoo. It can carry a mile or more. Both sexes hoot, with the female call higher pitched and consisting of 7 or 8 syllables. Even though the female Great Horned Owl is bigger, the male has a larger voice box and a deeper voice. Pairs often call together, with audible differences in pitch.

Great Horned Owls are one of the earliest species to nest in the Northeast, and are often brooding eggs as early as January. For nesting sites they use old hawk, eagle, heron or osprey nests, squirrel nests, tree hollows, or cliffs. Check out the Vermont eBird map to see all the sightings reported in January. From the first to the second Vermont Breeding Bird Atlas, Great Horned Owls decreased by 33% (57 to 38 blocks) with the greatest decrease in Taconic Mountains.

If you hear an agitated group of cawing American Crows, they may be mobbing a Great Horned Owl. Crows may gather from near and far and harass the owl for hours. The crows have good reason, because the Great Horned Owl is their most dangerous predator.

Great Horned Owls are covered in extremely soft feathers that insulate them against the cold winter weather and help them fly very quietly in pursuit of prey. Their short, wide wings allow them to maneuver in the forest while hunting prey.

A Bark in the Night

Red Fox / © K.P. McFarland

Adult Red Foxes are usually solitary until mating season, which begins this month and lasts until early March in New England. Red Fox attract each other with series of barking at night. High-pitched screams or barks at night, often thought to be Fisher, are usually calls from fox. Fisher are quiet animals.

Listen to the distant barking screams of a Red Fox recorded in Woodstock, Vermont.

During the cold New England winters, red foxes stay warm by growing a long winter coat. An adult fox rarely retreats to a den during the winter, but will instead curl into a ball in the open, using its bushy tail to wrap around its nose and footpads. Many times, they can be found completely blanketed in snow. With the onset of spring, red foxes shed their winter fur and prepare for warmer weather.

Troubled Beech

With all the leaves down, it’s hard to walk through the forest without noticing the pocked trunks of American Beech (Fagus grandifolia) trees. A mature tree with smooth gray bark is a rare sight now. The culprit is beech bark disease.

It’s caused by a unique relationship between an introduced insect called the Beech Bark Scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga), and Nectria fungi (Nectria coccinea var. faginata and N. galligena). This disease has been known in Europe since at least the 1840s, where it attacks European Beech (F. sylvatica).

It was accidentally introduced to North American at Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1890, on a shipment of ornamental trees.

The infestation spreads about 10 miles per year, mainly from the dispersal of Beech Bark Scale by wind and animals. It first appeared in New England in 1929 when it was found in Maine. By 1950 it was found throughout the entire state, and by 1960 it was found across New England. Today it is as far west as Wisconsin and south into North Carolina and Tennessee.

Since there are few natural controls known, the disease is likely to become established across the entire range of American Beech. The native Twice-stabbed Ladybird Beetle (Chilocorus stigma), aptly named for the two bright red spots on each side of its black back, preys on Beech Bark Scale, but isn’t able to drastically limit the population.

Beech Bark Scale is easy to see on infected trees in the fall. They exude small but noticeable white, waxy filaments on tree trunks. These wingless insects are parthenogenetic, egg growth and development occurs without fertilization by a male and all offspring are females. Adults lay eggs in the summer which soon hatch and the young nymphs, called crawlers, move into bark fissures or may be carried to other trees by wind or wildlife. Once the young crawlers settle down they push their stylet, a sharp needle-like mouthpart, into the bark and begin feeding and secreting the woolly wax cover that they use to help survive the winter season.

The minute wounds created by the stylets allow Nectria fungi to colonize. The fungal colonies cause cankers on the bark surface. This quickly leads to wilting of leaves and loss of twigs and branches. Eventually, the cankers cause enough damage around the tree that the trunk simply snaps in a wind storm. Beech snap is now common throughout the New England forest.

This is bad news for the wildlife that depends on beech for survival. Bear, deer and turkey rely on the energy rich beech nuts in the fall. The Early Hairstreak (Erora laeta), a tiny blue butterfly whose caterpillars feed on beech flowers, is found in beech forests. There is at least a glimmer of hope. Some resistant trees have been found and are now being produced in nurseries with the hope that they could be transplanted throughout the range to perhaps bring healthy beech slowly back to the forest.

This is bad news for the wildlife that depends on beech for survival. Bear, deer and turkey rely on the energy rich beech nuts in the fall. The Early Hairstreak (Erora laeta), a tiny blue butterfly whose caterpillars feed on beech flowers, is found in beech forests. There is at least a glimmer of hope. Some resistant trees have been found and are now being produced in nurseries with the hope that they could be transplanted throughout the range to perhaps bring healthy beech slowly back to the forest.

Nice read on this dark, foggy and rainy day.

Well, you can come here and enjoy -19F that rose to +8F for a high. Haha. Spring bird migration…it is just around the corner!

Bald eagle sighting flying low in Burke VT