Labrador Tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum) bursts into bloom in mid June on the Mount Mansfield ridgeline. / © K.P. McFarland

Here in Vermont, we dream of June during the darkest winter days. Verdant wooded hillsides glowing brightly under a robin egg sky. Warm afternoon breezes rolling through the valleys as we lounge by the clear waters of a cold river. The chorus of birds waking us each morning. The smell of freshly cut grass wafting through the window. Butterflies skipping from one flower to the next. We forget about the clouds of black flies, the hum of the mosquitoes and the rainy days. June is a dream here. Its days last forever. Here’s just a few of the natural history wonders for the month.

Carpenter Bees At Work Near You

Have you ever seen a large bee hovering around you like they are about to attack? And then suddenly they zoom off? This is common behavior of male Eastern Carpenter Bees as they patrol their small territories looking for intruders or mates. There’s no reason to be alarmed; males don’t sting. Only the dark-faced females can muster a sting, and usually only if handled. Male territories encompass about 60 feet around the nest site or food-plant area, and they will chase any interloper that comes near – birds, flying insects, people, and even, reportedly, the occasional airplane high in the sky.

There are over 300 species of native bees in Vermont, but there’s only one large carpenter bee, the Eastern Carpenter Bee (Xylocopa virginica), and they’re fairly easy to identify. At first blush they look like large bumble bees, but if you look more closely you’ll notice that they have shiny, black, and hairless abdomens. Peer even closer and you’ll see massive and sharp appendages, called galea, hanging down from the mouth. These are used to chew their way through wood, giving them their name.

Carpenter bees don’t eat wood. They gnaw through it, creating tunnels for nesting and resting in dead trees or branches, logs, or unfinished wood on structures. They prefer softwoods like pine, fir, or cedar, which are easier to excavate. With their sharp galea, a female chews a round entrance hole about a half-inch in diameter. It can take her up to two days to chew across the wood grain. Once the tunnel is about as deep as the length of her body, she turns ninety degrees and excavates more quickly going with the grain. If she comes to a knot, she’ll tunnel around it. Some nests have two or more tunnels that parallel the main hall, each over a foot long. They can use the same nest site year after year, sometimes by adding a new tunnel or lengthening an existing one. One studied colony was used for 14 years.

Carpenter bees are so-called solitary bees. Unlike honey bees or most bumble bees, there are no queens or workers, just individual males and females. Newly hatched females may live together in the nest with their mother during their first year, but after that each female will have its own nest and brood.

At the end of a tunnel, the female lays an egg on a loaf of pollen the size of a kidney bean. At just over a half inch, it’s one of the largest insect eggs in the world. The female chews the surrounding wood into a pulp to create a cardboard like partition that seals the egg within its own cell. Each tunnel can have up to eight cells. When they hatch, the grubs feed on the loaf of pollen.

Here’s what gets them in trouble. Carpenter bees can create nests in fences, outdoor furniture, and buildings. They select bare wood on roof eaves, fascia boards, porch ceilings, decks, railings, siding, and shutters. They will seldom bore into painted or varnished wood.

It takes years for carpenter bees to cause significant structural damage. You can minimize their damage by filling and sealing nest holes in the fall or winter with a small dowel or caulk and covering with fresh paint. Filling them in the spring or summer will just cause the female to make a new entrance hole. You can also provide alternative nesting sites in untreated cedar boards, their favorite wood.

Why not just eradicate them? Carpenter bees pollinate plants in 19 different families, from spring lupines to late-summer goldenrods. Like most bees, they enter the opening of a flower and reach in with their glossa, like a long tubular tongue, to suck nectar. They also gather pollen to carry away on their bristled-covered rear legs.

Carpenter bees are also cheaters. If the flower is too small or too long for them to reach with their relatively short glossa, they put their carpenter’s skill to work and simply cut a hole into the base of the flower for direct access to the nectar. Other bees will also sometimes feed at these nectar holes as well.

Over the last decade, carpenter bees have been moving farther and farther north. Keep watch for the hovering male signaling his territory around you and add your sightings to the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist! Check out the map of sightings and see if any have been observed near you.

Black Flies Aren’t Just Annoying to Us

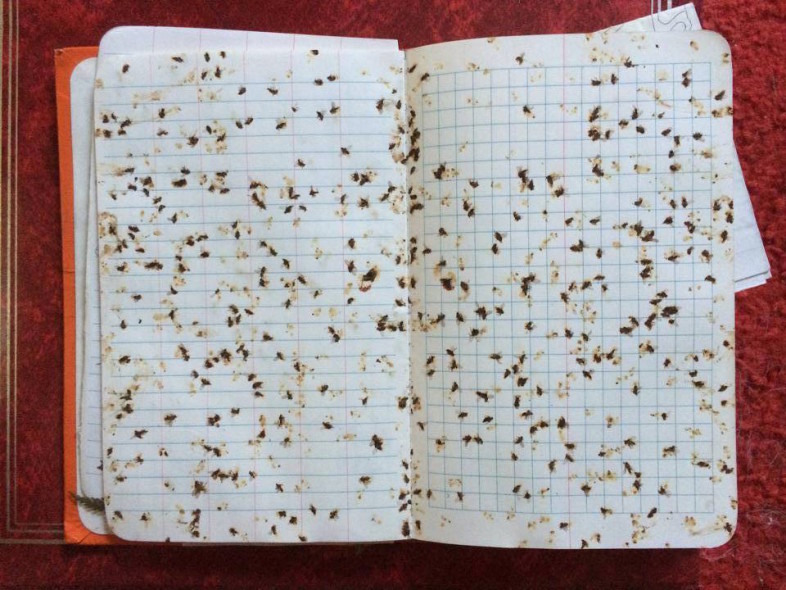

Noel Dodge was one of our best student interns on the Bicknell’s thrush project. He’s now a professional biologist and still working hard on conservation issues and still comes up to Mt. Mansfield from time to time to help us band birds. One day while banding Bicknell’s thrushes on Stratton Mountain, he decided to collect a sample of black flies around us. His method? Field notebook slaps. Here’s a few hours work on June 16, 2002. Field work can be tough! Imagine our necks and ears after that morning!

The Northeast is home to over 40 species of black flies. But only 4 or 5 are considered to be really annoying to humans. In some cases, black flies may not bite but merely annoy us, as they swarm about our head or body (Hint – they like dark objects. Choose clothing wisely). Only the females bite and fortunately, for us, most species feed on birds or other animals.

Biologists have found Peregrine Falcon chicks being killed by outbreaks of black fly swarms in the Arctic, possibly due to climate change. Farther south in Wyoming, researchers found black flies killed 14% of the Red-tailed Hawk nestlings that they monitored, and they were the only known cause of mortality. In 1984, heavy spring rains in the upper Midwest apparently caused ideal breeding habitat for black flies, whose populations exploded. Dense clouds of them attacked nesting Purple Martins causing widespread die-offs and colony-site abandonments. They can even get on the nerves of nesting Common Loons. Black flies can be a big problem for many nesting birds.

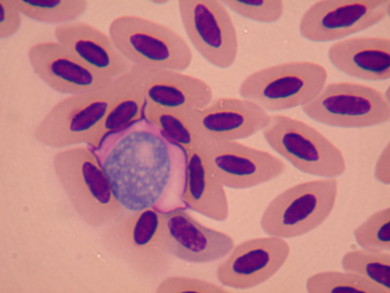

But they just don’t bite birds, they also transmit disease. Leucocytozoon is a genus of parasitic protozoa. They use Simulium black fly species as their definitive host and birds as their intermediate host. There are over 100 species and more than 100 species of birds have been recorded as hosts.

VCE teamed up with Vermont-based biologist Ellen Martinsen and found that in Vermont’s Green Mountains, 67% of females and 48% of males were infected by Leucocytozoon sp. Our colleagues in New Brunswick, Canada found that 69% of the Bicknell’s Thrushes they sampled were parasitized by Leucocytozoon.

Black flies breed exclusively in running water. Some species live in large, fast-flowing streams, others in small, sluggish rivulets. Almost any kind of permanent or semi-permanent stream is occupied by some species. Large black fly populations indicate clean, healthy streams since most species will not tolerate pollution.

Black fly females lay their eggs on vegetation in streams or scattered over the water surface. The eggs hatch in water and larvae attach to submerged substrate. They feed by filtering water for tiny bits of organic matter. Once the larvae are mature, they pupate underwater. Emerging adults ride bubbles of air, like a hot air balloon, to the surface and fly away. They mate nearby and females search for a blood meal before laying eggs. And that’s when they find you.

Helping House Bats Raise Pups

Little Brown and Big Brown bats are frequently found in buildings, and sometimes in tree hollows or under peeling bark, and are often referred to as “house bats.” These two species are common visitors to residences from about mid-April to October, although the Big Brown Bat may overwinter in attics.

During the summer months, females of both species form colonies, sometimes in large numbers, in attics, barns, sheds or under shingles. This is where they give birth and raise their young. Males also frequent buildings, either alone or in small groups. The females give birth to a single pup in late June or July. At birth each weighs less than an ounce with flesh colored skin covered with fine silky hair. They open their eyes for the first time within 24 hours. The pups in the colony will sometimes huddle close together for warmth while their mothers go out to forage for insects during the night. They won’t be able to fly for 21 to 28 days.

Little Brown Bats begin to emerge from the attic to forage for the night. You can see one slipping out for the night in the red circle. / © K.P. McFarland

The Little Brown Bat used to be one of the most common tenants in some buildings and bat houses, but due to the devastating effects of a fungal disease known as White-Nose Syndrome, this species has suffered a 95 percent population decline in recent years. By putting up a bat house, you can provide critical roosting sites for bats in your area and benefit from their insect eating abilities.

Learn more about bat houses from the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. Listen to Outdoor Radio as they visit a colony and learn more.

How To Catch a Dragonfly AND TELL US ABOUT IT

Vermont has 142 species of dragonflies and damselflies, and catching one in a net is a lot more challenging than it might appear. So we’ll turn to an “encore edition” of Vermont Public Radio’s “Summer School” series. In one episode, VCE Research Associate Bryan Pfeiffer offered a lesson on swinging for dragonflies in the big leagues.

Thanks to the tireless efforts of odonate experts Mike Blust and Bryan Pfeiffer, and over 300 other observers, the Vermont Dragonfly and Damselfly Atlas covers the distribution of 150 species known from Vermont, including all of the resident and regular migrant species, as well as all known vagrants – individual insects appearing well outside their normal range. Blust and Pfeiffer conducted fieldwork across Vermont for years, with the help of other enthusiasts, and compiled an amazing dataset of Vermont’s odonates that we continue to grow today at the Vermont Atlas of Life.

One of our objectives is to document dragonfly and damselfly distributions that may be shifting as a result of climate change. For example, of the 31 species added to the state list since the year 2000, Vermont lies on the southern edge of five, none of which is common or appears to be expanding. However, Vermont lies at the northern edge of 16 of these new species, and 10 show signs of expansion, many becoming quite common.

You can help us record and map all the dragonflies and damselflies in Vermont, rare or common. Take digital photographs and submit your observations to Odonata Central or the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist. There is much to discover about biodiversity in our own backyards.

A Pitcher Plant’s Web of life

Pitcher Plant. /© K.P. McFarland

Find yourself a sphagnum covered bog in New England and you’re sure to find a pitcher plant. But peer a little closer and you’ll find a whole self-contained world within it.

Northern pitcher plants (Sarracenia purpurea) grow as a rosette and produce 6 to 12 new tubular leaves each season. A bunch of pitchers next to each other likely belong to the same individual. New leaves open every few weeks and the “pitcher” that is formed fills with rainwater. Leaves capture the sun for photosynthesis during their first year, but as they age they are used by the plant to capture prey for 1 to 2 years before they fall apart. The small prey die and break down in the pitcher. The plant absorbs nutrients from the prey that are not available from the acidic bog.

The prey are attracted to the pitcher by a sweet sugary secretion on the lip of pitchers, as well as color and scent. Because of a waxy, slippery coating on the lip of the pitcher, they sometimes fall into the water inside the pitcher and find it difficult to climb out because of very fine, downward-angled hairs on the walls of the leaf.

Nicholas Gotelli from the University of Vermont and Aaron Ellison from Harvard Forest studied the effects of increased inputs of atmospheric nitrogen from acid precipitation. They discovered that as more nitrogen is added to bogs the pitcher plants shift from producing water-filled pitcher-shaped leaves to flat leaves that are used for photosynthesis. This is an amazingly fast morphological change.

There is a complex web of life living within each pitcher. The base of the food web is comprised of captured prey, mostly ants and flies. These are shredded and partially consumed by Pitcher Plant Midge (Metriocnemus knabi) and Pitcher Plant Fly(Fletcherimyia fletcheri) larvae. Shredded prey are processed by a host of bacteria and protozoa. These are in turn prey to a filter-feeding rotifer (Habrotrocha rosi) and a mite (Sarraceniopus gibsonii). Larvae of the Pitcher Plant Mosquito (Wyeomyia smithii) feed on bacteria, protozoa, and rotifers. Older mosquito larvae (third instar) eat rotifers and smaller mosquito larvae (first and second instar).

Gotelli and Ellison found that the web of life extends outside of the pitcher too. The leaves exude a sugar that attracts ants. Some ants forage successfully while a few fall into the pitcher. Two moths, the Pitcher Plant Moth (Exyra fax) and The Pitcher Plant Borer (Papaipema appassionata), only use the Pitcher Plant as a host plant for their caterpillars to feed and grow. The larvae of the Pitcher Plant Moth can drain and kill individual pitchers. The Pitcher Plant Borer feeds on the roots and can sometimes kill the entire plant. Repeated or heavy feeding by the moth larvae reduces the amount of available sugar to the ants.

Check out the hidden world of the Pitcher Plant the next time you are on a boardwalk through a bog. Here are some bogs with boardwalks in Vermont:

Finding Ferns

One June day a few years ago I took a two-hour fern tour of Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park with a small group. We were able to find 22 species of true ferns and document 17 of those with photos on the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist. There are 36 species of true ferns known in the Park, out of the 65 species found in Vermont. Finding nearly two-thirds of the species in the Park in just a few hours was a lot of fun and incredibly helpful for learning and comparing the identifications of each species. There are over 8,000 fern observations in the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist, representing 62 verified species now.

Naturalist examines Goldie’s Fern closely. © K.P. McFarland

Ferns and their allies are seedless vascular plants. So how do they reproduce? Their life cycle has two different stages; the sporophyte (most of the mature plants you normally see), which release spores, and gametophyte, which releases gametes. The spores grow into tiny gametophytes with both male and female organs that release and capture sperm. A fertilized egg develops into a new sporophyte. It’s a very strange system. Check out this graphic that really helps to show how it all works.

Perhaps Vermont’s most famous fern is the Green Mountain Maidenhair Fern, which was formerly described in 1991. It is only known from about 7 places in northern Vermont and adjacent Quebec in rare serpentine soils.

You can find a key to the ferns and their allies at GoBotany and learn more about each species. From rare to common, there’s plenty to find and learn about Vermont’s ferns. Explore, find, photograph, and share your observations with the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist.