It’s always great to see these spring ephemeral wildflowers after a long winter, but to find all three together in one little patch…ecstasy. (Left to right: Carolina Spring Beauty, Sharp-lobed Hepatica and Bloodroot) / © Bryan Pfeiffer

The month of May is a show-off. Grass glows green under blue skies. Woodland wildflowers break out of the ground and demand attention. Trees flower and leaves burst from long-dormant buds. Songbirds arrive on southern night winds and liven the dawn with a chorus of song. May shouts of life and rejuvenation. Here’s a few bits of natural history for your May days.

Spring Ephemeral Woodland Wildflowers

Canada Violet (Viola canadensis) flowers below the trees before they fully leaf out. / © K.P. McFarland

Spring ephemeral wildflowers are perennial woodland plants that sprout from the ground early, bloom fast and then go to seed—all before the canopy trees overhead leaf out. Often found in calcium-rich woods, these “ephemerals” include Spring Beauty, Dutchman’s Breeches, Blue Cohosh, Hepatica, Wild Ginger, and a few others. Once the forest floor is deep in shade, the plant’s leaves wither away leaving only the roots, rhizomes, and bulbs underground. It allows plants to take advantage of full sunlight levels reaching the forest floor during a short time in early spring.

Many of these plants rely on myrmecochory—seed dispersal by ants. The seeds of spring ephemerals bear fatty external appendages called eliaosomes. Ants harvest and carry them back to their nests and eat them. The unharmed seeds are thrown into the trash bin and eventually germinate. A single ant colony may collect as many as a thousand seeds over a season. Unlike seeds dispersed by birds or wind, on average, a seed is only carried about two meters from the parent plant. With such short distance dispersal, forest fragmentation is a threat to the survival of spring ephemerals. Once these plants are gone from the forest, it is rare that they return.

Long-term flowering records initiated by Henry David Thoreau in 1852 have been used in Massachusetts to monitor phenological changes. Phenology—the study of the timing of natural events such as migration, flowering, leaf-out, or breeding—is key to examine and unravel the effects of climate change on ecosystems. Record-breaking spring temperatures in 2010 and 2012 resulted in the earliest flowering times in recorded history for dozens of spring-flowering plants of the eastern United States.

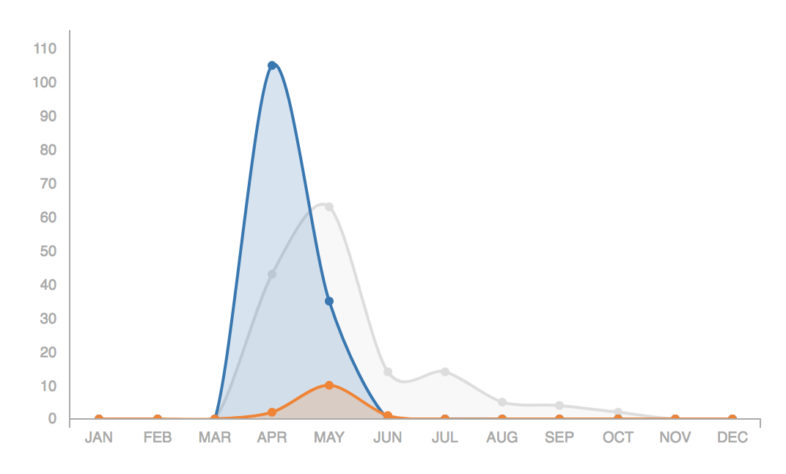

Bloodroot phenology from iNaturalist Vermont. flowering (blue), seeding (orange), and stage not noted (gray). Add your observations too!

Be like Thoreau. Help us monitor wildflower phenology. Find an area to monitor in a forest near you or simply record the status of those plants you find. You can enter your observations on our site at iNaturalist Vermont. Please include a photograph(s) of the plant.

Some Fabulous Spring Wildflowers (click to see field guide at iNaturalist Vermont and search for more):

Trout Lily (Erythronium americanum)

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis)

Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris)

Carolina Spring Beauty (Claytonia caroliniana)

Red Trillium (Trillium erectum)

Painted Trillium (Trillium undulatum)

Starflower (Trientalis borealis)

Dutchman’s Breeches (Dicentra cucullaria)

Squirrel Corn (Dicentra canadensis)

Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

Canada Violet (Viola canadensis)

Wild Ginger (Asarum canadense)

Sharp-lobed Hepatica (Anemone acutiloba)

Early Blue Cohosh (Caulophyllum giganteum) and Blue Cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides)

The Dawn Chorus Begins

From the seemingly simple trill of a Swamp Sparrow to the mimicry of the Northern Mockingbird, a songbird’s ability to learn is music to our ears. As Miss Maudie said in To Kill a Mockingbird, “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us.” The choir begins to warm up in early May and by the end of the month a full concert is conducted each morning.

This is when birders are most delighted. They can’t help themselves. They’re calling out each species as they hear the song, sometimes to themselves just to acknowledge the wonder, other times to people around them that might not be noticing the fine vocals. Bird watching by ear is a craft that takes years of practice.

Here are six tips to help you learn to bird by ear:

- Learn to listen. Stand and listen to each and every bird song you can hear. Learn to just pick them out first. Just notice them.

- Master the bird songs in your yard first.

- Associate songs with something memorable: ‘Drink your teeeeaaa” is what the Eastern Towhee says. Black-capped Chickadees call out, ‘cheeese burger.’

- Track the singing bird down and identify it visually.

- Go birding with experienced birders. Don’t be afraid to ask them lots of questions. Most love to pass on knowledge.

- Record them with your smartphone or other device and identify them and study them at home later. Before you know it, you’ll have them in your song book.

- eBird and the Macaulay Library have a fun new tool: the eBird photo + sound quiz. Quiz yourself on 20 images or sounds from birds anywhere in the world, all based on media uploaded by eBirders everywhere. Warning: your spare time may never be the same.

- Check out all the awesome recordings by birdwatchers on Vermont eBird and add your own.

- Be patient. It takes years to learn them all, but it is worth it!

SPRING EPHEMERAL BUTTERFLIES

Copulating West Virginia White butterflies. / © K.P. McFarland

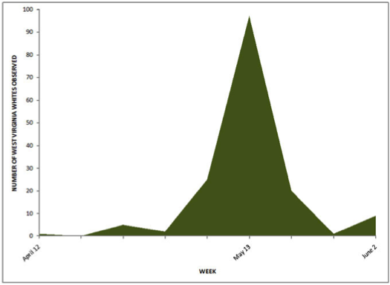

It’s not a gaudy butterfly. It isn’t the biggest or the smallest. In fact, it’s mostly just white. But this butterfly is unusual; it only flies in forests. It’s an ephemeral spring wildflower groupie.

To see this butterfly you need to get to rich, mature hardwoods with spring wildflowers early in the season. Our other, more common veined white, the Mustard White, does fly in woods, but it has distinct dark veins in its first brood (when it may be confused with West Virginia White). The West Virginia White always has faint gray scaling along the veins. And, unlike the Mustard White, it only flies early in the season. Their flight is slow and close to the ground. Follow a woodland stream until you find the host plant—and the butterfly. Its caterpillars only feed on Crinkleroot (Cardamine diphylla) and Cut-leaved Toothwort (Cardamine concatenata).

But there’s a dirty player in the field—introduced Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata). Garlic Mustard was first found in the United States about 1868 on Long Island. Invasions of Garlic Mustard are causing local extirpations of toothwort, and chemicals in Garlic Mustard appear to be toxic to West Virginia Whites, yet the adults are attracted to it and lay eggs on it.

Here’s a pair of spring form Mustard Whites, their close cousin, below for comparison. Add all of your butterfly sightings to eButterfly!

Licking the Spring Air

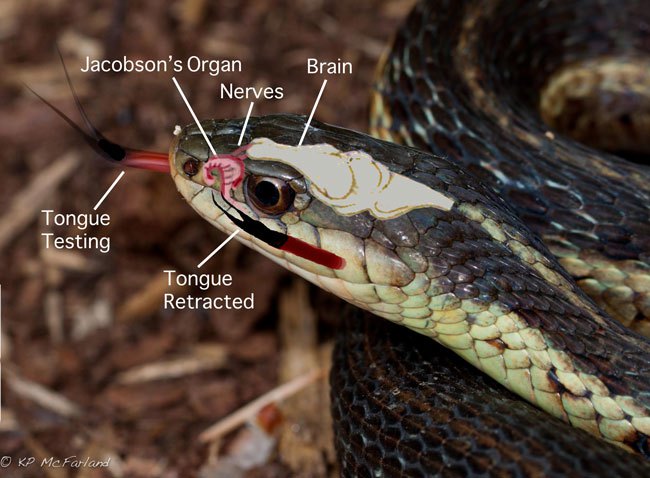

When it comes to tongue wagging, snakes beat even the best gossipers in town. Their tongues seem to flick in, out, and about incessantly as they bask in the spring sun. Like the ears of a gossiper, the snake’s tongue searches for information.

Garter snakes have especially colorful tongues—a bright red base and glossy black forked tips. They are also highly sensitive chemical collectors. With each tongue wag, airborne molecules are captured for analysis. Even with its mouth closed, the snake can slide its tongue through a space in its upper jaw.

Inside the mouth the tongue’s forked tips deliver captured molecules to the vomeronasal organ (VNO), also called the Jacobson’s organ, located in the palate below the nasal cavity. In mammals this organ opens to the nose, but in snakes it opens to the mouth via small ducts. The tips of the tongue are drawn over narrow grooves in the roof of the mouth, which pass chemical information into the ducts and up to the VNO.

The VNO has two openings in the palate. Its forked tongue may actually allow the snake to have stereo chemo-sensation. If an odor is stronger on one side, the snake can ascertain direction to the source. The chemo-sensation of the VNO in snakes is much greater than in most mammals. The next time you see a snake, don’t be alarmed by its tongue wagging. It’s just tasting your scent.

Spring Wildfire

Feeding holes from Pileated Woodpeckers shine bright with fire. / © KP McFarland

Wildfires in the northern hardwood forests are relatively rare, as evidenced by the fact that the forest is not fire-adapted like those in the southern or the western portion of the continent. Even in the southern New England hardwood forests, many of the trees, such as oak, hickory, and red maple, sprout vigorously from burned stumps and trunks after a fire. But the northern hardwood forest comprises more fire-sensitive species such as hemlock, beech, and sugar maple; anything more than a quick ground fire can kill a mature tree in the northern hardwood forest.

As if on cue, wildfires ignited around Vermont this spring. Several of our biologists are also volunteer firefighters, and while in the woods fighting wildfires, they’ve also got an eye on forest life. Read more in a blog post from biologist and firefigher Kent McFarland.

Licking Sap

While our human tongues are completely controlled by muscles, a bird’s tongue has small bones sheathed with tissue and muscle over its entire length. These small bones are collectively called the hyoid apparatus. And, woodpeckers and hummingbirds have an exceptionally large hyoid apparatus to support a long tongue.

Two bones wrap completely around the back of a woodpecker’s skull and attach near the base of the upper bill near the nostril to allow the tongue to extend and retract far from the mouth. When woodpeckers stick their tongue out they contract muscles which force the hyoid bones forward propelling it from the mouth.

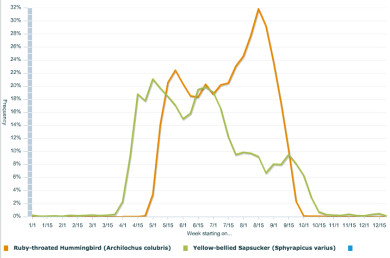

Annual phenology of Ruby-throated Hummingbird and Yellow-bellied Sapsucker from birdwatchers reporting observations to Vermont eBird. Hummingbirds arrive shortly after sapsuckers and take advantage of their sap wells.

But not all woodpeckers have long, barbed tongues. The Yellow-bellied Sapsucker has a relatively short tongue with feather-like bristles on the tip. These help the birds lap up sap via capillary action as it oozes from small rows of holes they drill into tree bark.

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds that have just arrived take advantage of these tapped trees in the early spring when there are few flowers. With their similarly long, brush-tipped tongue, hummingbirds hover near the holes and lick the sap. They can extend and retract their tongue about 13 times a second. They use the same technique to lap nectar from blooming flowers.

EGGS AND ALGAE

Egg masses with and without algae. / © K.P. McFarland

Peer into a woodland vernal pool in New England right now and you’re liable to find masses of developing Spotted Salamander eggs. Many of them have a green hue visible throughout the gelatinous mass. Most things lying in water eventually get coated in algae. But in 1927 Lambert Printz realized this was a special green algae only found on these eggs and formally named named it Oophilia, meaning egg loving, amblystomatis, from the genus name for spotted salamanders.

In the 1980’s biologists wondered if perhaps there was more to the relationship between algae and animal. They found that spotted salamander embryos grown without green algae didn’t develop as quickly. It was thought that the algae perhaps provided more oxygen for eggs in potentially oxygen-poor waters.

However, biologists recently reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science that they discovered green algae actually living inside the cells of developing spotted salamander embryos. In an Indiana University press release biologist Roger Hangarter said, “With the ability to use gene-specific probes, it is now possible to determine the presence of organisms that may not be easily visible by standard light microscopy. In the past, researchers looking with simpler light microscopy techniques than are available today failed to see any algae in the salamanders.”

This special symbiotic relationship is termed endosymbiosis, in which two species not only share living space with each other, but one actually lives inside the cells of another. They found evidence of green algae in salamander oviducts suggesting that transmission may occur from one salamander generation to the next via transmission through eggs.

Learn more about vernal pools on the VCE web site.

The first picture in your post shows a Sharp-lobed Hepatica. I’ve always wondered how you determine whether a particular Hepatica is Sharp-lobed and Round-lobed. They all look the same to me! Any guidance you can provide would be appreciated.

Love your newsletters!

The difference is in the leaves and bracts of the flowerhead. “Sharp-lobed” refers to the leaves with 3 deep lobes which are pointed on the ends of the lobes. Likewise the floral bracts have pointed tips. This compares to the “Round-lobed Hepatica” where the ends of the leaves are more rounded, as are the tips of the bracts.

This is truly beautiful. Love the focus on ephemera. Thank you!

As always Kent, wonderful writing and photos. Thanks.