Red Fox Sparrow (Passerella iliaca iliaca). Factumquintus/CC-BY-SA-3.0.

Late each fall, and then again early in spring, Fox Sparrows visit my backyard. Large and brightly colored, at least by sparrow standards, they are a harbinger of the changing seasons and a delight to watch during their brief stay. Sometimes they even sing during their brief spring stop-over, a beautiful set of downward, slurred whistles.

Most field guides and general references depict Fox Sparrows as a bird that nests only in the boreal forest of Canada and Alaska and the high mountains of western North America. The eastern subspecies of Fox Sparrow—the Red Fox Sparrow (Passerella iliaca iliaca)—has traditionally been considered a passage migrant through New England, stopping off briefly in late fall and early spring as it travels to and from its breeding grounds in eastern Canada. However, several summers ago, while working in western Maine, I encountered several singing males in mid-June. As this seemed quite late for birds supposedly migrating through the region, I was intrigued. When I returned to camp that evening, I pulled off the shelf a copy of Ralph Palmer’s Maine Birds, now almost 80 years old but still the definitive reference on the birdlife of Maine. As expected, Palmer describes Fox Sparrow as a “transient,” a passage migrant that moves through the state early in spring and again late in the fall but most certainly not a breeding species. So what were these birds that I’d found singing in the middle of June doing? Why was a species that supposedly only migrates through the region present during the breeding season and apparently defending territories?

These questions led to a two-year long effort to piece together its current breeding range, which I’ve written about in a paper submitted for publication at the scientific journal PeerJ. The story goes something like this:

Beginning in the early 1980s, birders in southern Quebec—well south of the known range of the species—began noticing Fox Sparrows during the summer. A few years later, scientists working on a study of how efforts to control spruce-budworm outbreaks in Maine affected bird populations found a Fox Sparrow that they suspected was nesting (thanks to Jeff Cherry, the field leader for this study, you can see the eBird checklist for this record here). In 1983, a Fox Sparrow nest was finally discovered in far northwestern Maine, a stone’s throw from the Canadian border.

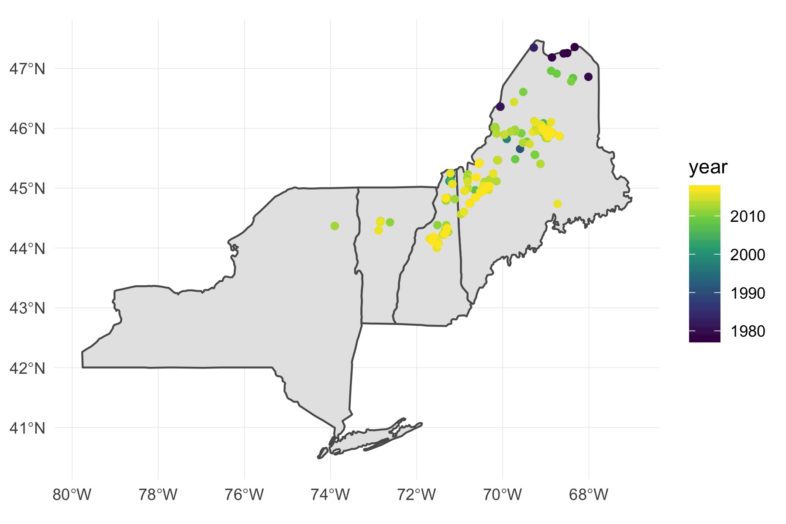

After that, the floodgates seem to have opened. Fox Sparrows were reported nearly every summer in increasingly far-flung locales, first in the mountains of western Maine, then near Mount Katahdin, and finally, by the mid-1990’s in northern New Hampshire. In 1996, a birder discovered the first Fox Sparrow nest in New Hampshire, near the northern town of Pittsburg. From there, they appear to have moved south, and are now a regular summertime resident throughout the White Mountains. A few have even showed up on Mountain Birdwatch surveys conducted in the Green Mountains of Vermont and at least one individual has been seen and heard singing on Whiteface Mountain in the Adirondacks of New York. Based on an analysis of checklists submitted to eBird, it seems that Fox Sparrows are showing up wherever there are young, dense forests of spruce and fir, whether it be the stunted krummholz forest of our mountaintops or the old clearcuts of commercial forestlands scattered throughout northern New Hampshire and western Maine.

A species never known to nest in New England prior to the 1980s, Fox Sparrows have expanded their breeding range south by about 400 km in a span of less than 30 years, and seem to be on track to continue this remarkable journey. If past trends are any indicator of the future, they will likely become at least occasional nesters in suitable habitat in Vermont and New York (and indeed, may already be). Although I haven’t conducted an exhaustive search of the ornithological literature, I can think of few other bird species that have shifted their range so dramatically in such a short period of time, and none that have done so by moving north to south!

The breeding range of Fox Sparrow (Passerella iliaca iliaca) has expanded southward out of Canada’s boreal forest by several hundred miles since the early 1980s. Colored dots on the map show the location and year of eBird checklists that contain an observation of Fox Sparrow.

What explains this phenomenon? Right now, the answer is anyone’s guess. One possibility, though, is that we’ve inadvertently created a lot of suitable habitat for Fox Sparrows through our logging activities. The Fox Sparrow vanguard arrived in Maine at about the same time that large areas of the state’s forests were being clearcut in response to the great spruce-budworm epidemic of the time. Dog-hair stands of spruce and fir sprung up in many of them. As a bird that loves thick stands of young evergreens, this may have offered a wealth of new nesting habitat that allowed new populations to become established and grow.

We’ve grown used to stories of climate change causing rapid shifts in the distribution of plants and animals across the globe, with southern species marching northward as the climate warms. Very rarely, though, do we see the opposite: a boreal species charging southward.

Much remains to be learned about our new breeding resident: what is driving the southward expansion, what implications exist for the species that make up the biological communities colonized by Fox Sparrows, and where Fox Sparrows will finally stop. In the meantime, though, keep an eye out as you explore the wilds of the northeast and don’t be surprised to see one of these boisterous northerners next summer. And if you do—don’t forget to post your sighting on eBird!

In paragraph four you mention a study on the effects on bird populations on spruce budworm control measures. Could you be willing to share that citation?

Thanks.

Here is the link to the ebird checklist that will give you the citation.

https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S35906856

You can contact me directly if you have questions. I was the field leader for that study.

Thanks Jeff, I was part of the study too. I wondered, that’s why I asked for the citation. I didn’t think there had been that many studies like it back then, and I remembered the fox sparrow. Lynn

This is an intriguing article! I’m curious, though, by your alternate use of the word “expanding” and “shifting”. “Expanding” suggests to me that the birds continue to nest in their historical locations, and maybe the population is increasing. Whereas “shifting” might mean that fewer and fewer of them are nesting in the northern part of their historical range, and more are nesting in the southerly regions. Thanks for clarifying!

Well, as far as I know, “expanding” is probably more accurate. You’re correct that shifting implies a mix of gains and losses, which doesn’t appear to be the case with Fox Sparrows. The data that I’ve seen about populations in Canada suggest that they are stable, so it doesn’t seem that the southward advance of the population is accompanied by a retraction elsewhere. That said, though, I don’t think we have great data about Fox Sparrow populations along the northern edge of their range. It would be really interesting, though, to look more closely at those populations to see what’s happening with them.