Where is Konza Now? Quick Links to Location by Date:

August 31, 2018

September 4, 2018

September 9, 2018

September 11, 2018

September 17, 2018

September 24, 2018

September 26, 2018

October 11, 2018

October 23, 2018

October 30, 2018

November 13, 2018

January 15, 2019

May 22, 2019

So many people wish to be a bird, even if just for a moment. I felt waves of envy when I watched a video of a man in a motorized hang glider imprinting a migration route for hand-reared Whooping Cranes by leading them across the sky. A similar glider offered a bird’s eye view of flying geese for the breathtaking film “Winged Migration,” allowing us to tag along on the birds’ journey.

We all can’t jump into hang gliders, but thanks to technological advances there are other ways to follow a wild migratory bird through its entire, year-round movements.

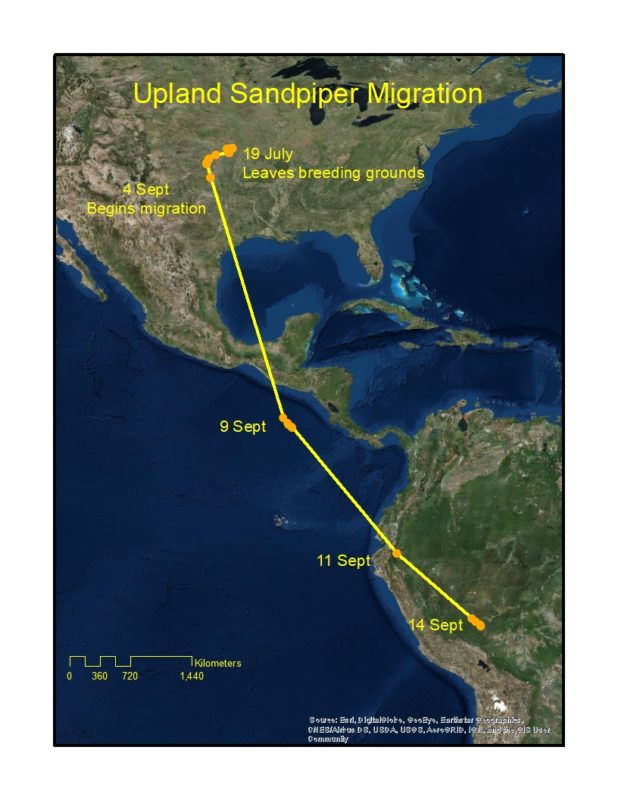

We are currently “live” tracking a free-living Upland Sandpiper. A shorebird that has nothing to do with shores, the Upland Sandpiper is a long-distance migratory bird that lives in grasslands and travels 6,000 miles to South America each winter. In April 2016, we captured this female sandpiper (we call her Konza), graced her with a solar-powered geolocator, and have been following her every move ever since. Funding for this project was provided by the Department of Defense Legacy Program.

The Upland Sandpiper we are tracking, sporting her solar-powered satellite geolocator. We have been following her every move since April 2016, thanks to funding from the Department of Defense Legacy Program. (Photo courtesy of R. Renfrew.)

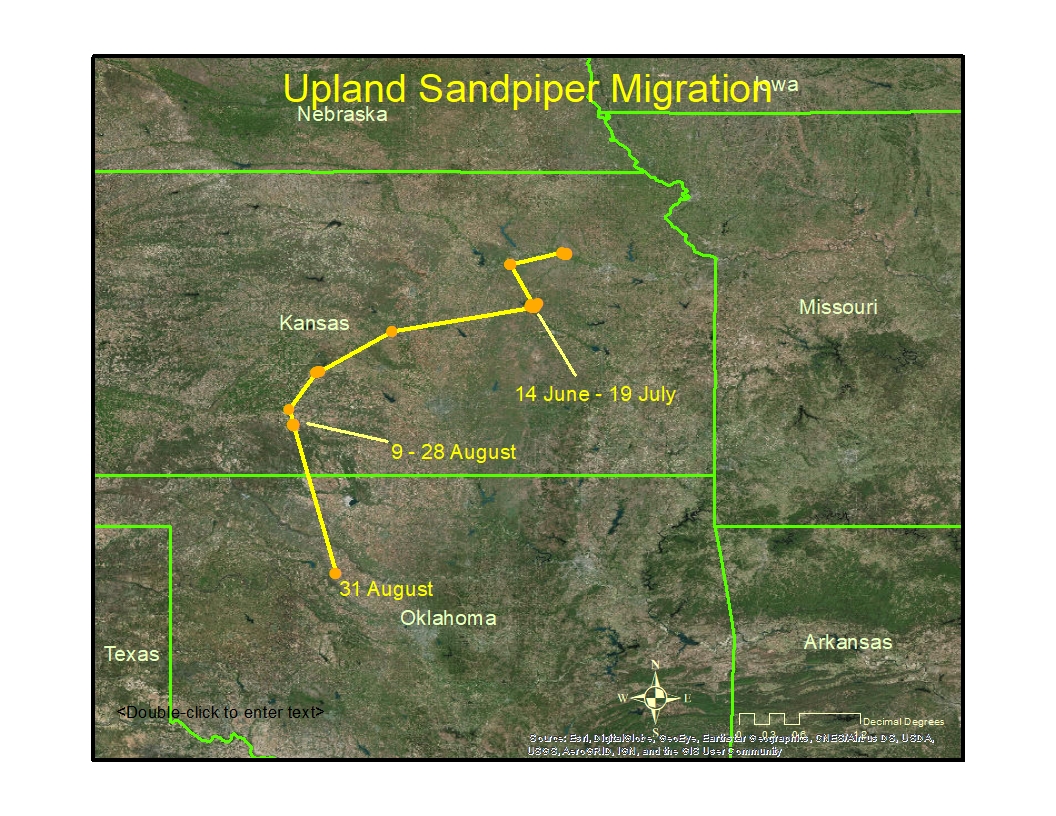

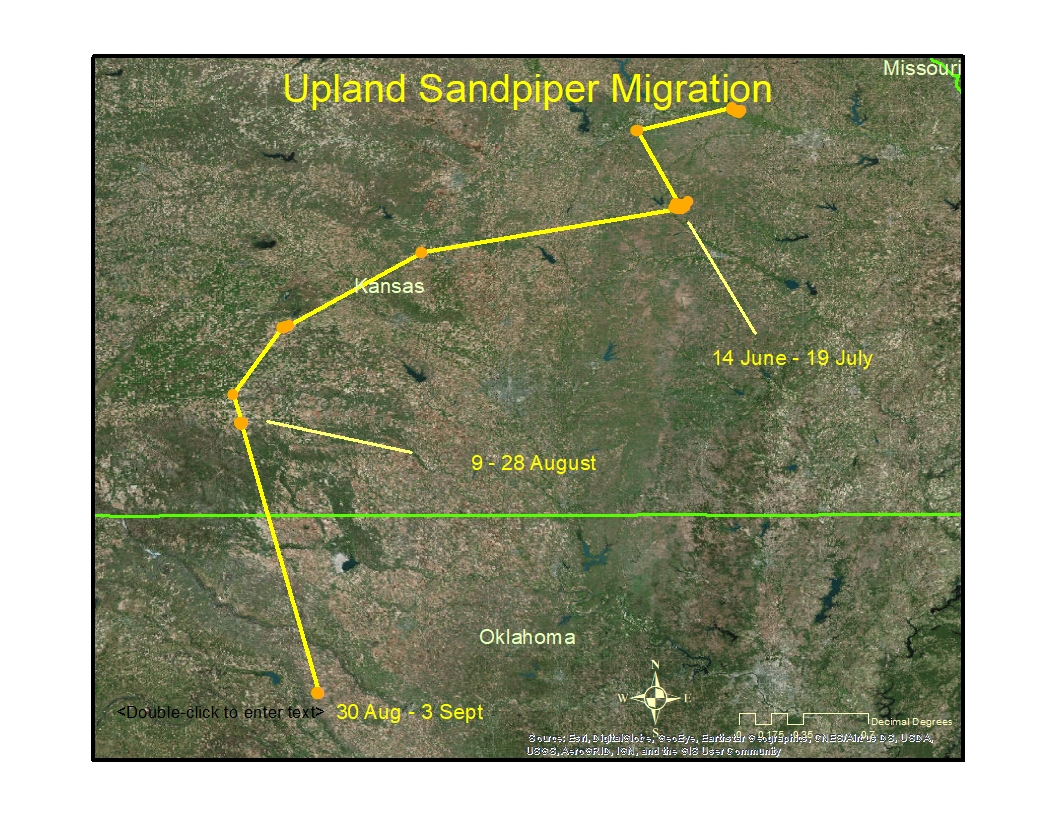

Starting from her breeding grounds in Kansas, we will post new maps to show where Konza travels, stops, and overwinters, as an Argos satellite detects and records her location and transmits the data. As we embark on year three of tracking her moves, we promise to not give out any spoilers.

Watch Konza head back to the wild after receiving her solar tag in 2016:

August 31, 2018

As of today, Konza is already on her way south, about 400 km southwest of her breeding area, recorded this morning in Oklahoma USA. Where will she go next? Stay tuned!

Current location: Oklahoma, USA

Countries visited: USA

September 4, 2018

Konza is still in the same location in Oklahoma, undoubtedly fattening up for the journey ahead. The diet of Upland Sandpipers is 97% insects year-round, and some of the heaviest weights have been recorded in September, just before their long flight south (Houston et al. 2011). When we captured this bird on 23 April 2016, she weighed 196g. Although we cannot definitively know the sex of an upland sandpiper, females weigh more than males, and birds that are heavy or light enough can be assumed to be female or male, respectively. The average mass of all nine presumed females we captured in spring 2016 was 191g, while the 10 presumed males we captured averaged 136g.

We’ll post an updated map and social media alert once Konza is on the move again!

Current location: Oklahoma, USA

Countries visited: USA

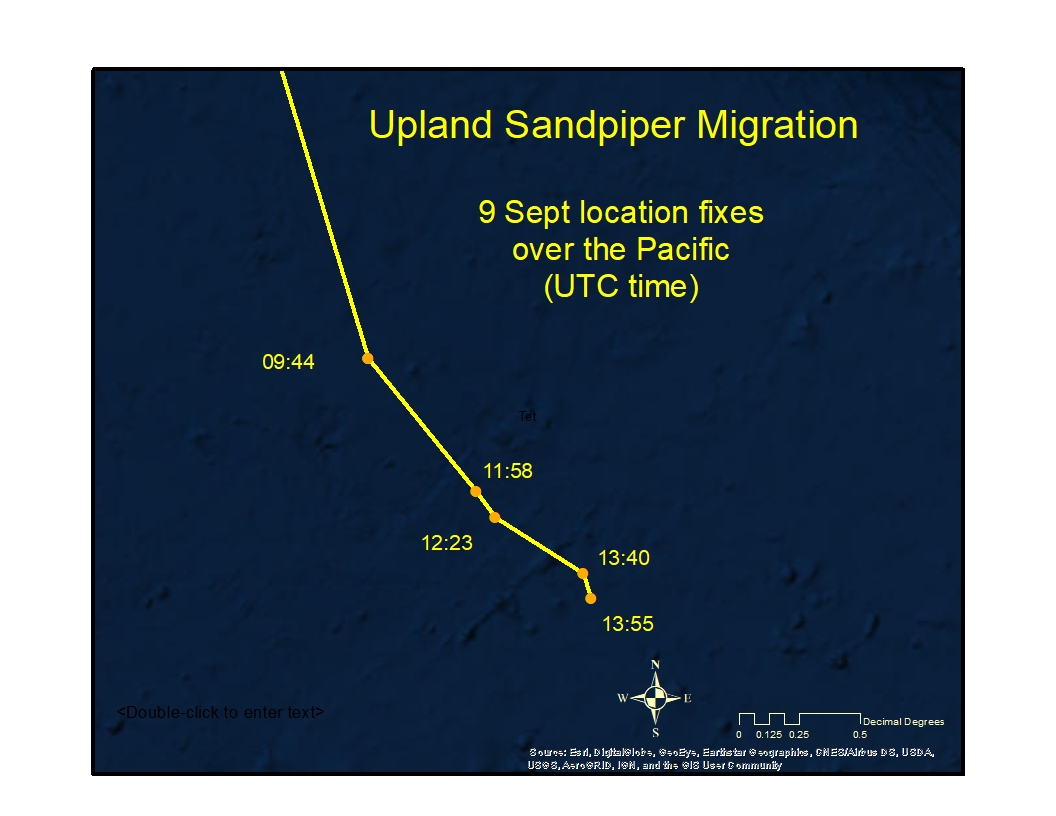

September 9, 2018

Konza is over the ocean!

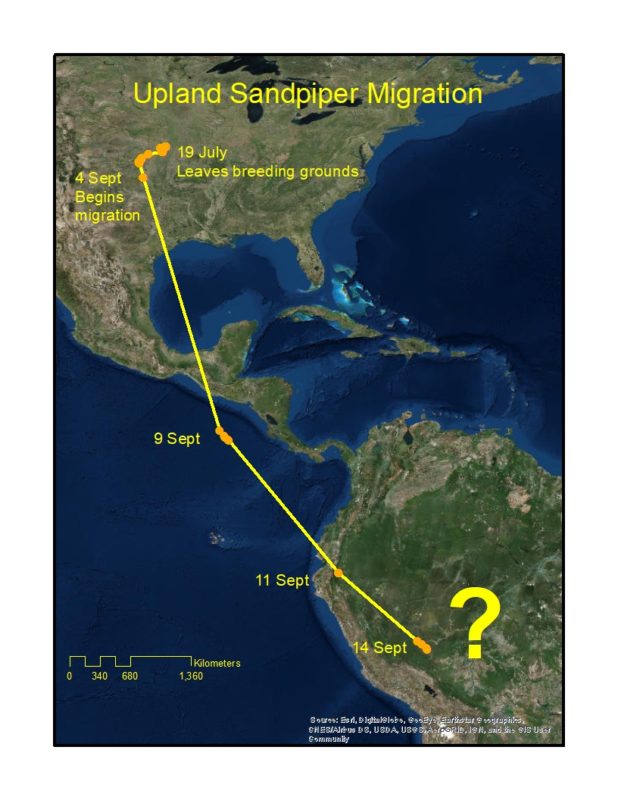

Konza, the Upland Sandpiper carrying a solar-powered satellite tag, left her pre-migration staging location in Oklahoma on 4 Sept. Then her tag went quiet for four days, which isn’t unusual for this technology; a tiny solar-powered battery takes time to charge, especially when under cloudy skies. But yesterday, on 9 Sept., we got what we’ve been waiting for, and the wait was worth it!

Konza is south of Central America, over the Pacific Ocean, on her way to South America! “Over the ocean,” you say? “Where does she stop to eat and sleep while on this trans-continental flights?” The answer: she doesn’t. You may recall reading about one of our other Upland Sandpipers (here) that flew for four days non-stop over the Pacific Ocean without food, water, or much sleep.

“How is that even possible,” (you ask while munching on a piece of fruit while sitting at your desk) “and what do you mean by ’much sleep’? How can she sleep at all while in flight?”

First, birds’ guts grow dramatically larger (to take in more food) as they prepare for long migration flights, and then the gut shuts down during flight to save energy. Birds take advantage of favorable winds and use a host of navigational cues (including smell, celestial cues, and the Earth’s magnetic fields [which they can see!] to navigate. They can even compensate for wind drift if they get blown off course, and yes, they can sleep while in flight by shutting down one hemisphere of their brain at a time.

We’ll give you a minute to let all of that soak in. Meanwhile, Konza is still powering across the Pacific Ocean at a steady ~22 mph on her way to… Well, you tell us! Donate here to keep her transmission signal alive, and tell us where you think she’ll land in South America.

Fall Migration Statistics

September 11, 2018

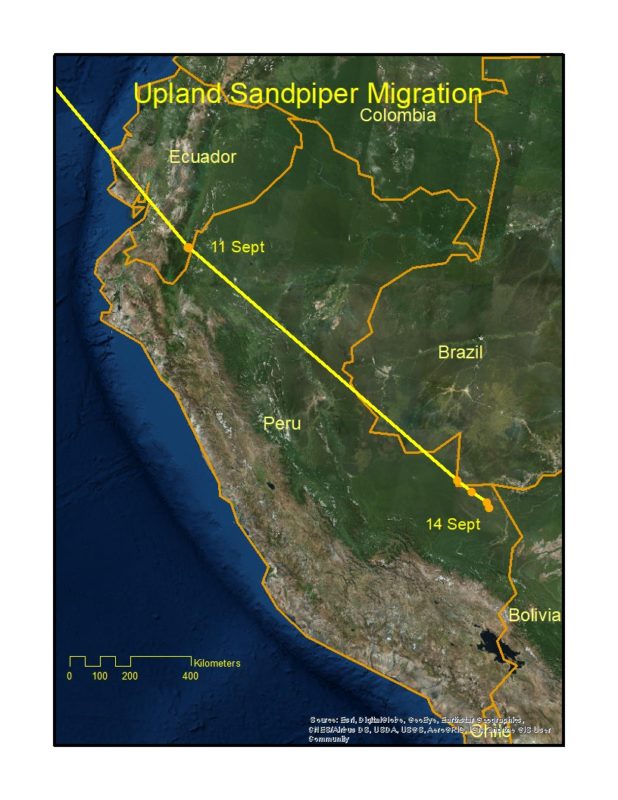

Land ho in Ecuador! And with a fascinating tale to tell… But stay tuned, because Konza still has a long way to go.

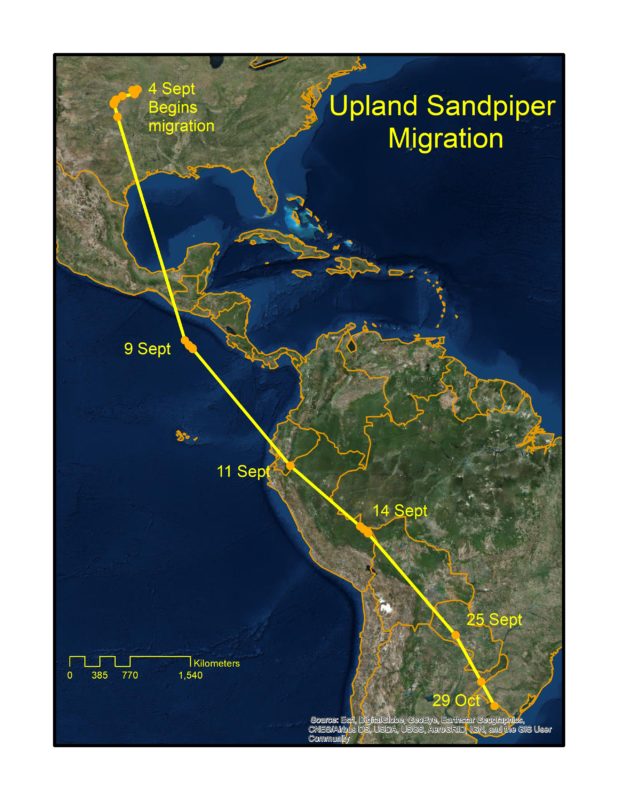

In our last entry, Konza was flying over the Pacific on 9 September. Over the next 48 hours, she flew at least 1,930 km to eastern Ecuador, very close to the border of Peru.

Konza not only endured her oceanic journey, but she also successfully flew past the lakes of Ozogoche in the Andean mountains, where strangely enough, Upland Sandpipers are known to rain from the sky. “Ozogoche” is a merging of the word “ushu,” meaning desirous to eat meat, and “juchi,” meaning lonely. It is such a fascinating tale of Ecuador indigenous people and migrating Upland Sandpipers, that Joe Houlberg, a native of Ecuador, is making a film about it.

Konza not only endured her oceanic journey, but she also successfully flew past the lakes of Ozogoche in the Andean mountains, where strangely enough, Upland Sandpipers are known to rain from the sky. “Ozogoche” is a merging of the word “ushu,” meaning desirous to eat meat, and “juchi,” meaning lonely. It is such a fascinating tale of Ecuador indigenous people and migrating Upland Sandpipers, that Joe Houlberg, a native of Ecuador, is making a film about it.

An Upland Sandpiper washed up on the shore in the Lakes of Ozogoche region in Ecuador. Photo: © Joe Houlberg

A local woman collects a “sacrificed” Upland Sandpiper in preparation for cooking. Photo: © Joe Houlberg

Each year hundreds of migrating Upland Sandpipers wash up on the shores of lakes in Ozogoche between September and mid-October. It is said that the birds “commit suicide” by flying head first at very high speeds into the lake. For the twenty-five local indigenous communities in the region, this act of sacrifice is sacred. “Cuvivie” they call the species, based on the sound that it makes. For hundreds of years, the communities have celebrated the arrival of the sacrificed Cuvivie, which they collect along the shores to feast on. The indigenous of Ecuador celebrate the Upland Sandpiper with great fanfare out of their appreciation and respect for the bird that dependably provides for them every year.

Note: Since leaving her breeding grounds on September 4, Konza has flown 5020 km (3120 mi) in one week.

Fall Migration Statistics

Current location: Ecuador: in a narrow grassy valley at 1500 m elevation, and <10 km from the Peruvian border

Countries visited: USA, Mexico (flyover), Guatemala (flyover), El Salvador (flyover), Costa Rica (flyover), Colombia (flyover), Ecuador

Distance flown from 2018 breeding grounds: 5020 km (1920 mi)

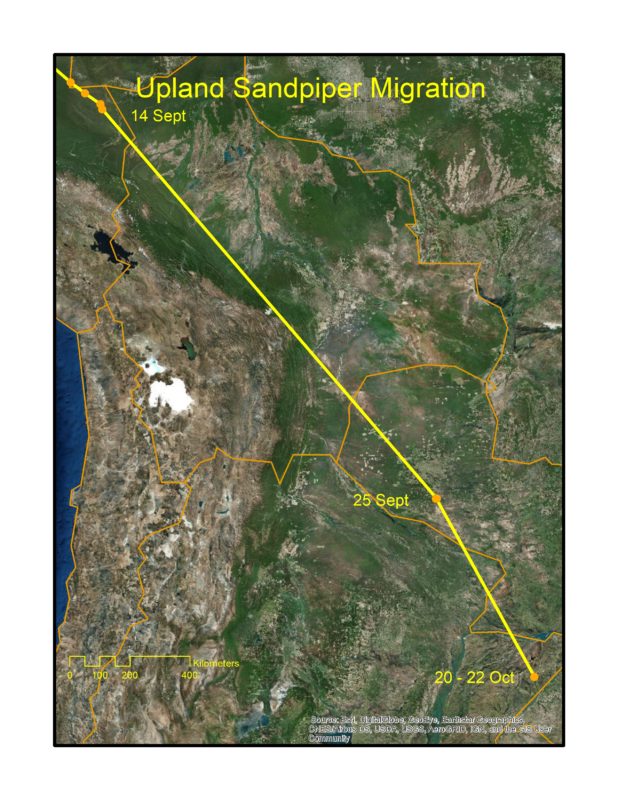

September 14

From ocean to forest – breaking down barriers

When we last tuned in on September 11th, Konza had terminated her transoceanic crossing over the Pacific with a brief stop in southeastern Ecuador, near the Peruvian border. Our latest transmission on September 14th shows Konza 1,300 km farther, in southeastern Peru near the border with Bolivia. The last three transmissions from her solar satellite tag on the 14th are within a few hours of each other, and she was still on the move. She has been passing over forested regions of eastern Peru.

To a grassland bird, dense forests are fairly similar to oceans when it comes to migration. Long-distance migrants such as Upland Sandpiper and Bobolink usually fly nonstop over enormous forested regions (think: the Amazon). They tend to stop on either side of these vast, inhospitable tracts of land to rest and refuel. Our best guess is that she has since made a landing somewhere in the open savannas of northern Bolivia. Another transmission from Konza is soon due; all we need now is for the satellites to be in the right positions to detect her 5g tag. Keep an eye out – we’ll be in touch again soon!

Fall Migration Statistics

Current location: In the air over Southeastern Peru, near the Bolivian border.

Countries visited: USA, Mexico (flyover), Guatemala (flyover), El Salvador (flyover), Costa Rica (flyover), Colombia (flyover), Ecuador, Peru

Distance flown from 2018 breeding grounds: 6320 km (3930 miles)

September 24, 2018

No Word from Our Bird.

The latest update on Konza is… there is no update. There have been no transmissions since our last update on 14 September.

Don’t panic just yet.

This has happened before, with a variety of ultimate outcomes. Sooner or later, every tag stops reporting, never to be heard from again. It is usually difficult, if not impossible, to know whether the bird perished (and the tag is in water, on the ground, or in the stomach of an unfortunate predator), or if the tag simply stopped functioning. Tags can fail internally, or the antenna becomes damaged from water or wear and tear.

One Upland Sandpiper we tracked previously made it as far as Texas by October, and subsequent transmissions came in only every few months until the following March—and then there was nothing. If during this time the tag had reported from the same location in Texas, we would have inferred that the tag was lying on the ground, either because the bird had shed the tag or died. However, at one point the tag reported from about 15 km away from the previous position, suggesting that the bird was still wearing the tag, but the tag had ceased to function properly.

We are rooting for one or more of the other potential explanations for this radio silence from Konza. We have had cases where a tag went silent for days or weeks, and then Bam! It started transmitting regularly again. We can only speculate as to why this happens.

We do know that in order to transmit a tag’s location, satellites need to “see” the tag and triangulate on the location. Konza may be in a spot where the tag simply cannot communicate with the satellites. For example, if Konza is in a dense forest or a narrow valley (such as a river channel), the possibility that a satellite’s path will cross in the right place to obtain a fix on her tag is greatly diminished.

Transmissions may be further inhibited if she isn’t taking flight and instead remaining on the ground, in which case the antenna is on or very close to the ground. Or, perhaps the solar-powered tag is not getting enough charge during a major weather event; or, perhaps the bird preened her feathers so that they are covering the solar cells.

We don’t know, and we may never know. We can only patiently wait and hope that Konza survives with her tag intact. Welcome to the world of suspense and uncertainty experienced by scientists who track migrating birds!

You can be confident that if and when we hear from Konza, we will update you immediately. Meanwhile, try to get some sleep.

September 26, 2018

We’ve Heard from Our Bird!

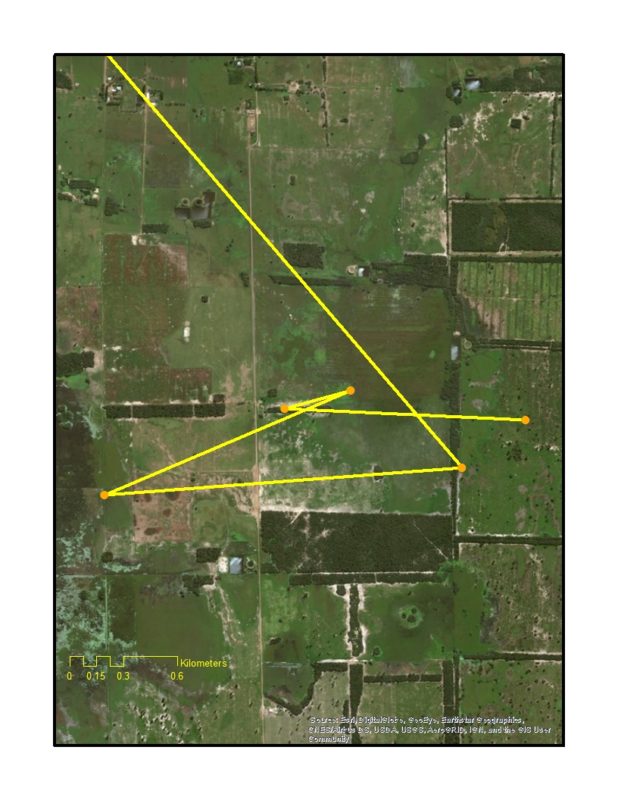

The wait is over! Last night Konza’s tag pinged five times in the span of four hours, all from an agricultural field in Paraguay. Check out the map below to see her movements on this new landscape.

You might recall we last “saw” Konza 11 days ago in Peru, near the border of Bolivia. She has since traveled through Bolivia, but she probably stopped there at least once. Now we find Konza at the southern tip of a region in Paraguay known for its Mennonite farmers.

Konza has now survived perhaps the most challenging legs of her journey: the Pacific Ocean, the Andes, and the vast forests of Peru. Crossings over these inhospitable habitats require adequate fat stores and cooperative weather; therefore, it may come as no surprise that for most bird species the migration period is considered the riskiest in the annual cycle.

Once Konza crossed into Bolivia, there was ample open habitat for her to choose from. In our three years of following her, this is her first known stopover in Paraguay. “Stopover” is a hint. From what we know from past years, she has yet to complete her southbound journey to her wintering grounds. Go Konza, go!

Fall Migration Statistics

Current location: Agricultural fields in Paraguay.

Countries visited: USA, Mexico (flyover), Guatemala (flyover), El Salvador (flyover), Costa Rica (flyover), Colombia (flyover), Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay

Distance flown from 2018 breeding grounds: 8,020 km (4,980 miles)

October 11, 2018

No News is Not Always Good News.

Since our last update on 26 September, we have not received a single transmission from Konza.

While this 15-day transmission gap is longer than the last worrisome hiatus, we still hold out hope that she is out there, alive and well. As we mentioned in our 24 September update, there are a number of explanations that could account for Konza’s radio silence. If Konza did perish, her tag could still be functional, but lying on the ground in a position such that it is not being charged by the sun or detected by satellites. These two lengthy transmission gaps in a row could perhaps point to a compromised or gradually failing tag. We can only guess. We sent word of her last location—in Paraguay—to bird conservation colleagues in the area in case they knew someone who could look out for her.

We continue to patiently wait and hope that Konza is alive with her tag intact. We’ll wait another month, and if we haven’t heard from her, submit our final post. Meanwhile, if her tag pings us a location, rest assured you’ll hear from us right away!

Over and out, for now.

Fall Migration Statistics

Last known location: Agricultural fields in Paraguay

Last known countries visited: USA, Mexico (flyover), Guatemala (flyover), El Salvador (flyover), Costa Rica (flyover), Colombia (flyover), Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay

Last recorded distance flown from 2018 breeding grounds: 8,020 km (4,980 miles)

October 23, 2018

Save your fears for Halloween – Konza has come through again!

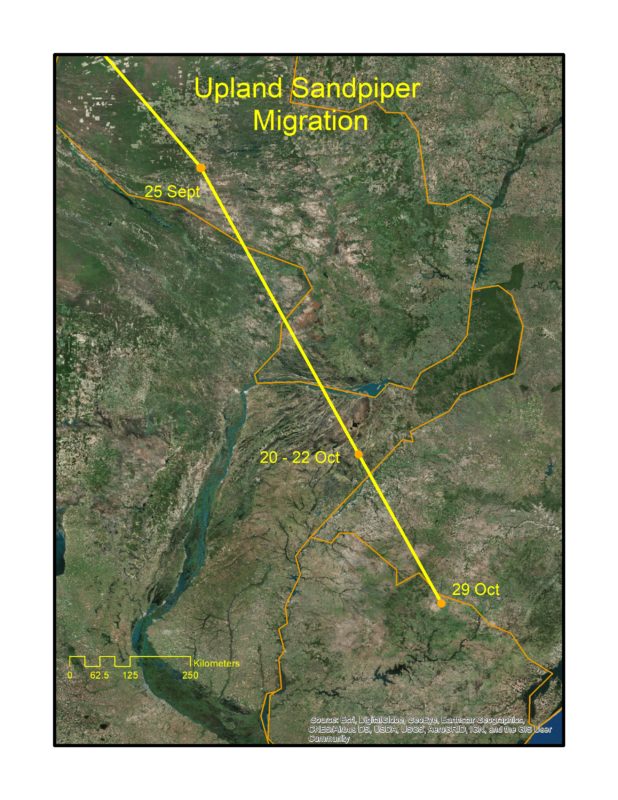

Konza is still with us! A pair of Argos satellite transmissions on October 20th and 22nd now places her in northeastern Argentina, the major host country for wintering Upland Sandpipers and in a region within their core wintering range. Konza is 400 miles southeast of her last location, reported nearly a month ago. Neighboring Uruguay is also home to Upland Sandpipers this time of year, where they can be found on vast cattle ranches and other agricultural fields.

When tag transmissions are few and far between: The few, intermittent data points received lately from Konza could suggest her solar tag is failing. Perhaps components degraded in severe heat, or moisture snuck into the sealed unit. Maybe her antenna became worn. Alternatively, perhaps it’s working just fine, but sitting at an angle that causes her feathers to block the solar cells from recharging. Whatever the case, we will now hope that her tag will continue to transmit locations!

The day between these last two transmissions from Konza, an iNaturalist user posted some photos the likes of which we have never seen before: a dead Upland Sandpiper in the middle of a city. This individual was found in Buenos Aires, about 400 miles south of Konza’s current location. It’s the first we’ve heard of a dead Upland Sandpiper found in a city, but if it was to happen, Buenos Aires would be a likely location.

© Romi Galeota Lencina,/ CC BY 4.0 iNaturalist observation 17743580

The timing of this report was quite a coincidence with Konza’s recent transmissions, although not exactly kismet for the deceased bird, which appears to have suffered a collision with a building or wire. Like many other species of birds during their migration, Upland Sandpipers fly at night, and can become disoriented by city lights. Collisions with buildings is a common but largely preventable hazard to migratory birds.

Konza may not have finished her southbound journey yet. In past years she’s been known to proceed a bit further. Plus, she doesn’t necessarily stay in one place all winter. Researchers using geolocation technology are finding that movement patterns of many migratory bird species are more complicated than we had previously assumed. We know almost nothing about whether Upland Sandpipers repeat their migratory patterns from year to year, and to what degree they may be “site-faithful,” returning to the same migration stopovers or wintering grounds each year. In this third year in a row of following Konza, each data point she provides is gold. We are witnessing an Upland Sandpiper’s movements across multiple years for the first time, ever.

You’ll hear from us next when we hear from Konza. If you don’t lose hope, neither will we.

Fall Migration Statistics

Last known location: Wetlands in northeastern Argentina

Last known countries visited: USA, Mexico (flyover), Guatemala (flyover), El Salvador (flyover), Costa Rica (flyover), Colombia (flyover), Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina

Last recorded distance flown from 2018 breeding grounds: 8,660 km (5,380 miles)

October 30, 2018

Konza adds one more country to her extensive travelogue.

The globetrotting sandpiper continued her southeast journey for another 212 miles during the last week, bringing her just 10 miles inside the northern border of Uruguay.

A known favorite of Upland Sandpipers everywhere, Uruguay boasts vast expanses of cattle ranches where much of the global Upland Sandpiper population spends the winter. Their mainly insectivorous diet has not been studied in South America, but in North America they often feed on grasshoppers, crickets, and beetles (including the larval stage) as well as a variety of other taxa, including weevils, spiders, snails, earthworms, and even crawfish (Houston et al. 2011).

Organophosphate insecticides are known to be highly toxic to birds, and their use on crops in South America caused concern about harming species such as Upland Sandpiper that feed in agricultural fields. One study tested the blood of migratory shorebirds in Uruguay, Paraguay, and Argentina, and found that Upland Sandpipers were not being exposed to these pesticides at harmful levels. They did find evidence of exposure in the Buff-breasted Sandpiper, another migrant with a winter range that overlaps with the Upland Sandpiper (Strum et al. 2010). In recent years, however, the use of organophosphates has been phasing out as it is gradually replaced by neonicotinoids—which pose major problems for some insects, and potentially the birds that forage on insects or treated seeds (but that’s a different story).

Fall Migration Statistics

Last known location: Ranchlands of northern Uruguay

Last known countries visited: USA, Mexico (flyover), Guatemala (flyover), El Salvador (flyover), Costa Rica (flyover), Colombia (flyover), Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay

Last recorded distance flown from 2018 breeding grounds: 8,995 km (5,590 miles)

November 13, 2018

Where in the World is Konza?

Apparently, Konza has found a suitable spot to rest her weary wings, at least for now. We received several transmissions from Konza’s geolocator tag placing her at the same location in Uruguay that we last reported on October 30.

She is foraging on insects by day, perhaps at a more leisurely pace now, and roosting right on the ground at night. Although we expect that she may make another move, she won’t be in any particular hurry to do so, and won’t need to travel as far. Food is abundant in South America’s austral summer, presumably enough to warrant the long trek.

Konza is probably loosely affiliated with others of her kind right now. Upland Sandpipers can be found in the same fields but they are somewhat dispersed or scattered. Unlike birds that flock during the non-breeding season to benefit from “safety in numbers,” Upland Sandpipers do not feed or roost in groups.

So… has she settled down into her new winter home? Assuming we continue to receive transmissions, we will post again when (and if) she makes her next move!

Fall Migration Statistics

Last known location: Ranchlands of northern Uruguay

Last known countries visited: USA, Mexico (flyover), Guatemala (flyover), El Salvador (flyover), Costa Rica (flyover), Colombia (flyover), Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay

Last recorded distance flown from 2018 breeding grounds: 8,995 km (5,590 miles)

January 15, 2019

Radio silence does not equal radio (or bird) death.

We have not abandoned you, nor have we been hiding behind doubts or fears that Konza has perished. We have kept our promise to you.

Our promise was to report the next time Konza moved, or if we had evidence of her passing. Neither of those events has occurred. So… we are breaking our promise, but only because we don’t want you to forget about Konza!

While this is not Konza, this lovely photo can help us imagine her enjoying Upland Sandpiper life in Uruguay! / © Rollin Tebbetts

Konza’s geolocator tag is still beaming coordinates every few days from Uruguay, within a 3-km radius of our last update location. This is interesting because we anticipated that she might have moved from this place after a few weeks, which she has done before. One has to wonder what compels her to stay versus trying out another spot. Is it an abundance of easily-acquired insects? Social cues from other Upland Sandpipers in the area? Perceived and/or actual protection or freedom from predators or disturbance? It may be a combination of these and other factors.

We are fairly sure, although we can’t be certain, that Konza is alive and well, and that we are not instead receiving transmissions from a tag lying on the ground. How do we know this? A tag transmitting from the ground would likely result in fewer transmissions and low-quality location data, and eventually, a complete halt in transmissions if the solar cell isn’t well-positioned to charge the battery, or the antenna is obscured. We are still seeing regular transmissions with quality data—a good sign!

So like Konza, we sit tight. We wait to see what she does (or doesn’t) do. Since she likely won’t take to the skies and head north for another few months, a change in her wintering location is still very much in the realm of possibilities. We’ll keep you posted, as promised!

May 22, 2019

Ummm… Konza?

Long time no see, Konza fans! You may be wondering why this update has taken so long. Well, it’s because we wanted to wait a little while to collect more data before reporting back.

You see, since December Konza’s solar-powered geolocator tag has been regularly reporting—from Uruguay. That’s not right. By now she should have landed on her breeding grounds on the Konza Prairie in Kansas. During the first two years that we tracked her movements, her solar tag revealed that she began her northbound migration around 20 March, give or take a few days. Like most other Upland Sandpipers, she arrived at her breeding grounds around mid-April. But this year, according to her tag, she hasn’t moved from her overwintering area.

Apparently, the tag has been sitting on the ground in the grasslands of Uruguay with the solar cells facing up (allowing the tag to remain charged) and in such a way that it is still able to communicate with satellites. If the bird had succumbed to a predator, the tag likely would have been damaged, laying on its side, or upside down. The tag’s upright position and ongoing functionality suggests it may have simply fallen off, unharmed. The harness that kept the tag in the proper position on Konza’s body is made of material that is not intended to last forever, but to eventually break down. Continual exposure to the blazing sun and intense ultraviolet radiation in South America likely helped the process along.

We suspect, and would also like to believe, that Konza is now back on her breeding grounds after flying north, liberated from her extra baggage. Thus, we conclude our story of Konza, grateful to her for giving us a better understanding and appreciation of the species’ extraordinary migration. May our payback be the conservation of her species.

(Side note: On my recent trip to Colombia, I spotted this Upland Sandpiper on its northward migration. Perhaps this bird and Konza shared the same wintering ground? We’ll never know, but it’s fun to think about in any case.)

You can read more about my trip to Colombia for grassland bird research and outreach on my three-part blog on the VCE blog. Click here for Part I.

Wow I love this. I’d love to track bar tailed godwits from alaska to nz.

Just a tremendous and inspirational story unfolding! Thank you!

Nice going Konza! So remarkable. Thank you for the updates

Oh, just when I thought we wouldn’t hear from her, she’s back! May the study move forward.

Great story!!! Please keep doing projects like this one.

We would love to! Always looking for ways to fund this kind of work, and encouraging colleagues to pursue it as well.