Common Loon in flight. © Lee Cordner

Those lucky enough to still be spending time on their favorite Vermont lakes may have noticed the disappearance of their resident adult loons, even with chicks still around. Carol Brooke-deBock has been following the two chicks on South Pond in Marlboro, but has seen only a single adult since late August. She actually observed one chick take a short flight, preparing for migration, on September 10. Other people have observed congregations of four to 18 visiting loons (usually on larger lakes). Denis LaPointe reported a consistent group of eight to nine adults on Norton Pond, and Nina Sharp has been sharing Caspian Lake with a group of 10 plus loons during her daily rows.

Loons undergo a partial molt in the fall. These two adults were part of congregation of over 20 loons on Lake Willoughby on November 4, 2007. © Ray Richer

So, when do loons take to the skies? To help answer that question, I’ll refer to a study on 32 loon pairs in Maine and New Hampshire by Lee Attix, who worked for Biodiversity Research Institute at the time. Starting in September, Lee followed loon pairs twice a week until late November (most of the males and females were banded and thus could be identified). He found a lot of variability in the timing of loon departures (see the range of dates compared to average in the table below), but also some general trends. As noted above, some adults start to move or even leave in September, while others stick around until late November. Chicks tend to depart in late October and November, but like the adults, some will leave in late September, and others never seem to get that migration restlessness (labeled “zugnruhe” in textbooks) and are still on the water when ice starts to form. Some of the study’s major findings include:

| Study of 32 Loon Pairs | Average departure time | Range |

| First adult | October 10 | Sept. 3 to Nov. 2 |

| Second adult | October 27 | Sept. 19 to later than Nov. 20 |

| Last chick | October 30 | Sept. 19 to later than Nov. 20 |

- Adults left separately; 62% of the time the female departed first.

- Some adults appeared to leave in early September. However, when an adult leaves his or her breeding lake, it’s often to spend time on a nearby pond and not to the ocean right away. There is a chance some of these early departing adults returned to the territory after being gone for days and weeks.

- Youngest chick when the first adult departed in early September: 8 weeks old

- Average age of chick when the last adult departed: 17 weeks old

- In two-chick clutches, one chick occasionally left before the second adult

- On average, the last chick left three days after the last adult. There were three cases where the chick left 22-37 days after the last adult. The departure of the last adult might be a signal for the chick to also leave, but not always.

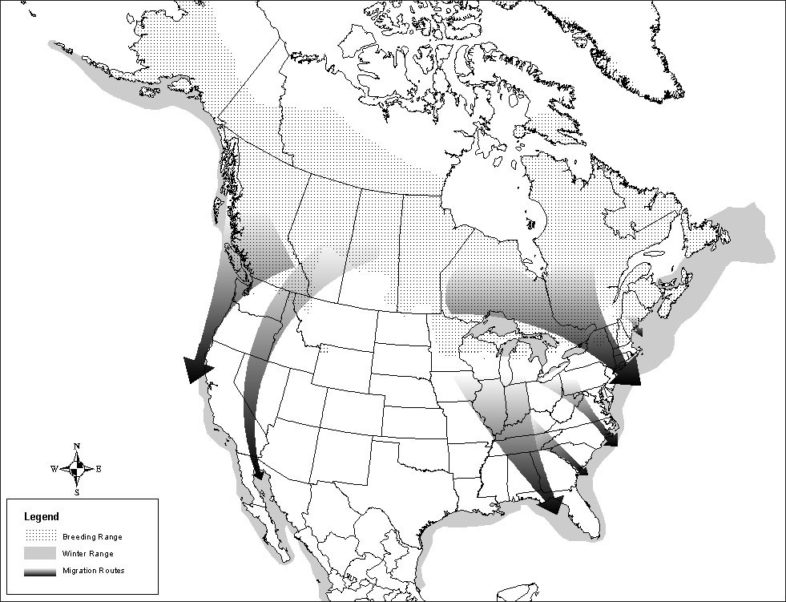

Most New England loons spend the winter off the Northeast coast, with a short migration period of only one to two days. Chicks figure out how to reach the ocean on their own, and likely take a much longer time getting there. Based on a sample size of one in a satellite telemetry study (Kenow et al., 2009), a lone Adirondack (NY) loon chick left in late November and took 56 days to puddle jump from lake to lake, eventually reaching Long Island Sound in January. Chicks usually spend several years on the ocean before returning to their natal lake region. As you’ll see in the map below, loons from the central part of North America will overwinter along central and southeast coasts and the Gulf of Mexico–they have a lot further to fly than New England’s loons!

One study (Paruk et al., 2014) that followed two loons from Saskatchewan revealed that one individual migrated to Lake Michigan and straight down to the Gulf of Mexico, while the other loon flew to the same location in the Gulf via Lake Erie, the Chesapeake, and across the Florida panhandle. How did they choose which route to take? We don’t really know, but once a loon learns a route, he/she sticks with it for years to come.

This map illustrates the variability in migration routes for Common Loons. (Image from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Status Assessment and Conservation Plan for the Common Loon)

After spending the winter eating seafood on the ocean, loons will return to northern, forested freshwater lakes and ponds in the spring, usually in April or early May. The magic of migration in all animals is fascinating; what initiates it, and how do species find their way back in spring to the same lake or forest stand? The sun, stars, Earth’s magnetic field, learned behavior, and genetics are several of the myriad factors that influence these amazing journeys.

References

Attix, L. Loon Conservation Associates. Personal communication and BRI internal report.

Paruk, J. et. al. (2014). Common Loons (Gavia immer) Wintering off the Louisiana Coast Tracked to Saskatchewan during the Breeding Season. Waterbirds 37(sp1):47-52.

Kenow, K., et al. (2009). Migration Patterns and Wintering Range of Common Loons Breeding in the Northeastern United States. Waterbirds 32(2): 234-247.

Eric, This is a great article. Very informative. Thanks. I always wondered how old a chick would have to be to migrate. Some that are hatched in mid or late July are late in leaving because of their age and abilities. Sometimes a younger chick will get caught up in the ice forming. I also found it interesting that the female leaves before the male, but in the spring, the male arrives first…And that the migration patterns vary…

Eric

Very nice article

Our loons have left Metcalf Od

But we are still seeing at times a loon stop by and leave within a few days,

We did see one this morning.

Hope you have a nice fall , looking forward to next spring

How are fires along the West Coast , and perhaps some in the East going to affect migration for our birds? The graphic of loon migration made me wonder. Will the poor air affect them?

Thanks Eric for all you do. I’m now residing in Sun City, Arizona and will not be on Lake Carmi anymore hopefully the Joe & Linda Craig will continue to observe on loon watch day. Best of luck!

Thanks for another great year Eric.

Thank you Eric! The baby loon in the little pond at Joe’s Pond is with 1 adult. Today the baby is doing a lot of “acrobatics” in the water and flapping its wings among other things. Is this how the prep for flight? (lots of scuba diving involved! :))

The acrobatics could be either preening, flushing the feathers thoroughly before more gentle preening. But if any wing rowing involved, this could be part of strengthening the wings for flight.

it seems just all of the above! Very beautiful!

Is it normal that 3 loons are still on the lake in the Laurentians, south of Tremblant on December 10?