The “Nose” of Mt. Mansfield is obscured by low clouds. Deep snowpack slowed our travel in the forest.

With deep snowpack on Mt. Mansfield remaining, yesterday we installed automatic bird song recording devices, phenology cameras that record the melting of snowpack and the greening of vegetation, and tiny data loggers that record air temperature and changes under the snowpack as it slowly melts. Together these give us a picture of the timing of migratory bird arrival coupled with the emergence of spring and finally summer in the high elevation fir forest.

Mike Manley from Stowe Mountain Resort took time out of his busy day to give Kent McFarland (behind the camera) and Jason HIll a lift up the mountain with all our gear.

With nearly 6 feet of snow at the famed “stake” on Mt. Mansfield, installing the equipment was going to be no easy task. Thankfully, Stowe Mountain Resort stepped in to help us once again. A trip up the face of the mountain in a snowcat made hauling equipment easy. From Toll Road access to sleeping quarters in the ski patrol building, over the last 25 years, they’ve always given us a huge logistical boost.

We know that anthropogenic climate change has already caused dramatic shifts in phenology in many parts of the world. For example, warmer average temperatures have caused spring wildflowers in New England to bloom a week earlier on average now than they did in the late 1800s. We know far less, however, about what changing phenologies mean for the health and viability of biological populations.

If warm winters mean that plants flower earlier and produce leaves earlier, what does this mean for the pollinators that visit the flowers or the herbivores that eat the leaves? Or what about the birds and other predators that eat the pollinators and herbivores? Is their phenology advanced, too, so that the timing of their emergence matches that of their food sources? Or do they find themselves suddenly out-of-sync with the resources that they rely upon?

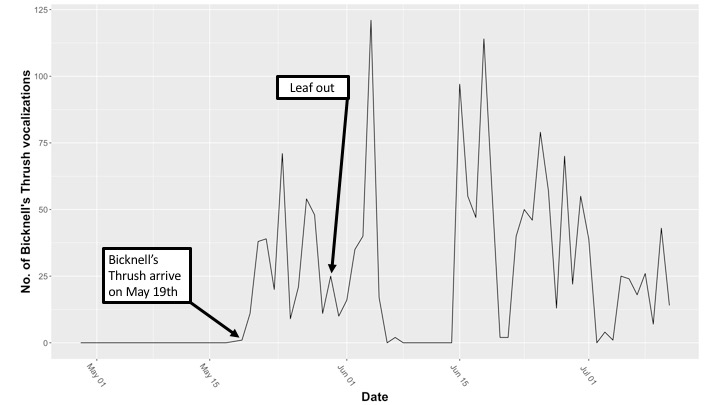

Automated recording devices give us calling frequency of Bicknell’s Thrushes. Notice the lack of vocalizations for a few days in June when a late snowstorm blanketed the mountain last year.

The goal of the Mansfield Phenology Project is to start answering these kinds of questions at site where we’ve been studying bird populations for nearly a quarter of a century. We’re using a variety of tools to track snowmelt, leaf-out, emergence of arthropods, and the arrival and breeding of migratory birds. We hope to learn how climate change is changing nature’s calendar on Mount Mansfield and whether plants and animals are adapting or suffering. Doing so will allow us to better document the impacts of climate change in an iconic New England landscape and better understand the conservation challenges facing its inhabitants.

This study is largely a long-term investment whose value won’t be clear for many years to come. Although one or two years of phenological data may reveal little, in 20 years a biologist – maybe one of us, but probably not – watching the sunrise over the Worcester Range, listening to a Bicknell’s Thrush sing, will be glad that data we’ve begun collecting under the Mansfield Phenology Project exists.

Watch this short video from last year about VCE’s Mount Mansfield Phenology Project and see how the equipment works and learn about some of the early results.

More Images from Mt. Mansfield

Automatic Recording Device deployed on Mt. Mansfield. Each morning and evening it will turn on and record all birds calling and singing for several hours.