Blackburnian Warbler, one of the 13 species that have significantly declined over the past quarter century in Vermont. / © Bryan Pfeiffer

VCE Releases a Major Report Today Documenting the Status of Vermont’s Forest Birds

A 25-year study of Vermont’s forest birds, including woodpeckers, warblers and other iconic species, has documented a 14.2 percent overall population decline during the period, raising concerns about birds and forests alike.

In one of the longest-running studies of its kind in North America, the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE) also issued practical recommendations for landowners who may want to conserve or manage their forests for bird abundance and diversity. Vermont forests support more than 125 bird species, VCE reported, and more than 47,000 jobs in the state.

“Whether we enjoy them at the feeder or in the woods, birds are vital to the health of our forests,” said Steve Faccio, a VCE biologist and principal author of a report on the study titled The Status of Vermont Forest Birds: A Quarter Century of Monitoring. “If we ignore these trends in bird populations, we risk losing not only birds but the vitality of our forests as well.”

“Whether we enjoy them at the feeder or in the woods, birds are vital to the health of our forests,” said Steve Faccio, a VCE biologist and principal author of a report on the study titled The Status of Vermont Forest Birds: A Quarter Century of Monitoring. “If we ignore these trends in bird populations, we risk losing not only birds but the vitality of our forests as well.”

While they require forests for nesting and migration, birds in turn promote forest health. They foster tree growth, for example, by consuming leaf-eating insects. Birds also disperse seeds and pollinate trees and other plants.

In its study, VCE methodically counted birds in 31 mature, unaltered forest tracts across the state each June for 25 years during the peak of breeding season. Overall, the counts revealed a 14.2 percent decline in abundance among 125 bird species from 1989 through 2013, with some species increasing, some decreasing and some remaining unchanged.

VCE went on to analyze in detail 34 of the most abundant and widely distributed forest bird species. Thirteen species (38 percent of the total) declined significantly during the period, including Canada Warbler, White-throated Sparrow and Great Crested Flycatcher. Eight species (24 percent of the total) increased significantly, including Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Mourning Dove and Black-throated Green Warbler. Thirteen species showed no significant change, among them the Vermont state bird, Hermit Thrush.

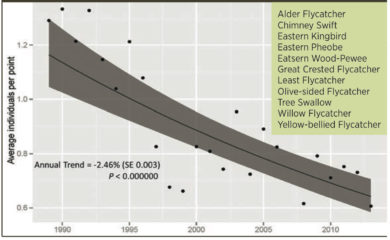

As a group, aerial insectivores (the 11 species listed in the box) have declined by 45% on FBMP surveys, corroborating an alarming trend in North America.

One guild of birds in particular — called “aerial insectivores,” which catch and eat insects on the wing — showed the most disturbing decline: a 45 percent drop in abundance over the 25-year study period. These included Chimney Swift, Eastern Phoebe, Eastern Wood-Pewee and Tree Swallow. The steep decline, VCE reported, most likely reflects broad-scale changes in insect populations, attributed to a variety of causes, such as pesticide use, acid deposition and climate change.

Any number of factors, including routine or “natural” changes in forest composition, affect bird populations. As a forest matures, its mix of birds will inevitably change. The study came during a period of statewide forest maturation, dwindling insect populations, and the arrival of West Nile Virus in Vermont. But VCE identified several “imminent, serious threats” to birds and forests:

- Fragmentation and Parcelization – As forests become fragmented by roads, development and other non-forest land uses, the amount of edge habitat increases, exposing interior forest breeding birds to predators and other threats. Additionally, many interior forest birds require large, contiguous forest blocks for breeding success.

- Non-native Invasive Species – More than half of Vermont’s tree species are threatened by three non-native insects: the emerald ash borer, Asian longhorned beetle, and hemlock wooly adelgid. Moreover, invasive earthworms are changing forest ecosystems by over-consuming leaf litter, which alters understory vegetation and soil structure and has been linked to declines among certain ground-nesting birds, including Ovenbird and Hermit Thrush.

- Climate Change – A warming planet may gradually but profoundly alter forest biodiversity, productivity and economics. Climate change alters the timing of routine seasonal events, such as tree flowering and insect emergence. When a bird species’ life cycle no longer coincides with these events, it may lose access to insect food for itself and to feed its young.

- Acid Deposition – Acidic compounds in rain, snow and fog leach nutrients from soils, limiting their availability for tree growth. Birds may be particularly sensitive to soil calcium depletion because they require calcium to produce eggshells.

VCE concludes its report with a series of practical recommendations for forest property owners who might be considering outright conservation or forest management to promote bird abundance and diversity. Among the objectives is “heterogeneity” in forest stands — trees of varying ages — which supports a full suite of Vermont’s native forest birds. The guidelines are not intended for commercial timberlands.

- Forest management in mature stands should strive to emulate natural disturbance events, such as wind and ice storms. These widespread, but infrequent events result in small-scale perforations in the forest canopy. Foresters can achieve this with small single-tree selection, or variably sized group selection cuts (0.1 to 1 acre).

- Retaining a high proportion of large trees can support canopy and cavity nesters. If snags are uncommon, retain or girdle medium to large, low-vigor trees.

- Conservation efforts should focus on uncommon or under-represented forest types, on large, contiguous forest blocks greater than 250 acres, and on corridors that connect existing conservation areas. When possible, forest land managers can allow natural processes to occur with minimal human disturbance.

With a 25-year study no small feat, VCE relied on its own staff biologists and a dedicated corps of skilled volunteer birdwatchers, who would rise well before dawn to follow rigorous and long-established protocols for counting birds. Year after year, the birdwatchers would walk the same route through a designated forest site, stopping at five pre-determined points and counting every bird they saw or heard over the course of 10 minutes. For the report, VCE analyzed 2,464 such point count surveys, in which a total of 32,381 birds of 125 species were detected, for an average of 13 birds per point.

With a 25-year study no small feat, VCE relied on its own staff biologists and a dedicated corps of skilled volunteer birdwatchers, who would rise well before dawn to follow rigorous and long-established protocols for counting birds. Year after year, the birdwatchers would walk the same route through a designated forest site, stopping at five pre-determined points and counting every bird they saw or heard over the course of 10 minutes. For the report, VCE analyzed 2,464 such point count surveys, in which a total of 32,381 birds of 125 species were detected, for an average of 13 birds per point.

“That VCE has been able to continue this effort for 25 years is a testament to the dedication of the researchers and the citizen scientists,” said Dr. Allan Strong, an ornithologist and associate professor in the Environmental Program at the University of Vermont. “Perhaps more importantly, much of our understanding of bird population dynamics comes from roadside counts, so having data from interior forests provides a unique perspective on how our bird populations have changed over the last quarter century.”

VCE continues to run the population surveys, known as the Vermont Forest Bird Monitoring Program, which is now in its thirtieth year. This latest analysis relies on data generated during the project’s first 25 years.

The Vermont Center for Ecostudies, with headquarters in Norwich, Vermont, promotes wildlife conservation across the Americas using the combined strength of scientific research and citizen engagement. Working from Canada to South America, from mountains to grasslands, VCE biologists study and protect birds, insects, amphibians and other wildlife. Joining VCE in the work is a dedicated corps of citizen volunteers.

Report available for download: Faccio, Steve; Lambert, J. Daniel; Lloyd, John (2017): The Status of Vermont Forest Birds: A Quarter Century of Monitoring. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4880837.v1

Comments (5)

Pingbacks (1)

-

[…] The bird population in Vermont’s forests has declined 14.2 percent over 25 years, […]

Not one single mention of feral cats. Feral cats should be shot on sight!

Feral cats should not be shot on sight. I agree that cat predation on songbirds is a huge factor in bird deaths, but so are windows, cars, etc. Feral cats are a problem that we created. There are many programs that help Vermonters neuter pets, but not enough people take advantage of them. They allow litter after litter and frequently abandon kittens on the roadsides or leave them in or outside of apartments when they move on. We have the ability as a society to address these issues, but the problem is getting people to do what is right. Also many people let their pets run free. There are many options available to fence your yard in or make catios to allow your cats to roam freely and safely within the confines of your yard, just punch in on Google Images: Cat enclosures. We have had our yard fenced in for 20 years for our 8 cats and it is very possible to do, though people used to laugh at the idea. Killing free-roaming cats is not the answer. The answer is education and getting people to take advantage of the programs available to neuter their pets and be responsible pet owners.

We created feral cats. It is not their fault we humans will not neuter and be responsible pet owners by fencing them in or building catios. We need more education about how to be responsible pet owners. Don’t blame the cats for our inadequacies. Germany has lost 76% of their insect biomass and 15% of their birds in one decade. That is 15% of their birds lost in 10 years. It has been linked to the loss of insects due to pesticides, particularly loss of water insects. We blame feral cats and let Monsanto run wild killing all our insects, weeds, birds and us. Pesticides have been found across the world in 75% of all insects tested. How do we expect any wildlife who lives on insects to survive, including we humans who depend on bees and flies to pollinate our food crops?

Seems different birds are now spending spring around my home in Jericho. More warblers and less chickadees. cardinals and blue jays. Even winter flocks of grosbeaks and golden finches have declined.

I did a Google search for “Missing VT birds” and found this post and I’m fascinated, saddened, and have a bit of understanding.

I don’t live in VT, but I have been going to the same hunting & fishing cabin near Middlebury for over 20 years now for winter weekend, usually in January or February. So, kind of a similar study that VCE is conducting, with admittedly much looser parameters, of course. And not with the intention to study the birds, obviously.

But. For years, we would place bird seed on the windowsills and place a suet cake nearby while we were there. Part of the experience of being up there was watching the birds. The chickadees, especially. They spent hours, sometimes the entire day it seemed, flying down to the sill and picking the seed up. We could see them up close, only a few inches and the windows themselves between us.

The last time I was there in 2019, right before the pandemic, there were noticeably fewer chickadees coming over to visit. The trip was on hiatus the past few years due to the pandemic, but we finally got back there a few weeks ago. It saddens me to report that we didn’t see a single chickadee the entire time we were there. Not one. Honestly, we didn’t see or hear a single bird the entire trip.