Five to seven days of nonstop flight across an ocean, between continents. This mind-bending feat of endurance is undertaken twice each year by Upland Sandpipers (Bartramia longicauda) migrating between North and South America. For those of us who gear up for a two-hour car ride (complete with map and weather reports, coffee, snacks, and a queue of podcasts), a 20,000 km (~12,500 mile) annual journey seems almost impossible to comprehend. Especially when you consider that sandpipers are carrying nothing but the feathers on their backs.

Biologists have long known that Upland Sandpipers migrate between breeding grounds in the northern United States and Canada to their wintering grounds in the Pampas ecoregion of Uruguay and Argentina, but via which course and exactly when they traveled remained a mystery… until now. VCE’s recent paper in the Open Access journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution unveils surprising new information about the species’ migratory patterns.

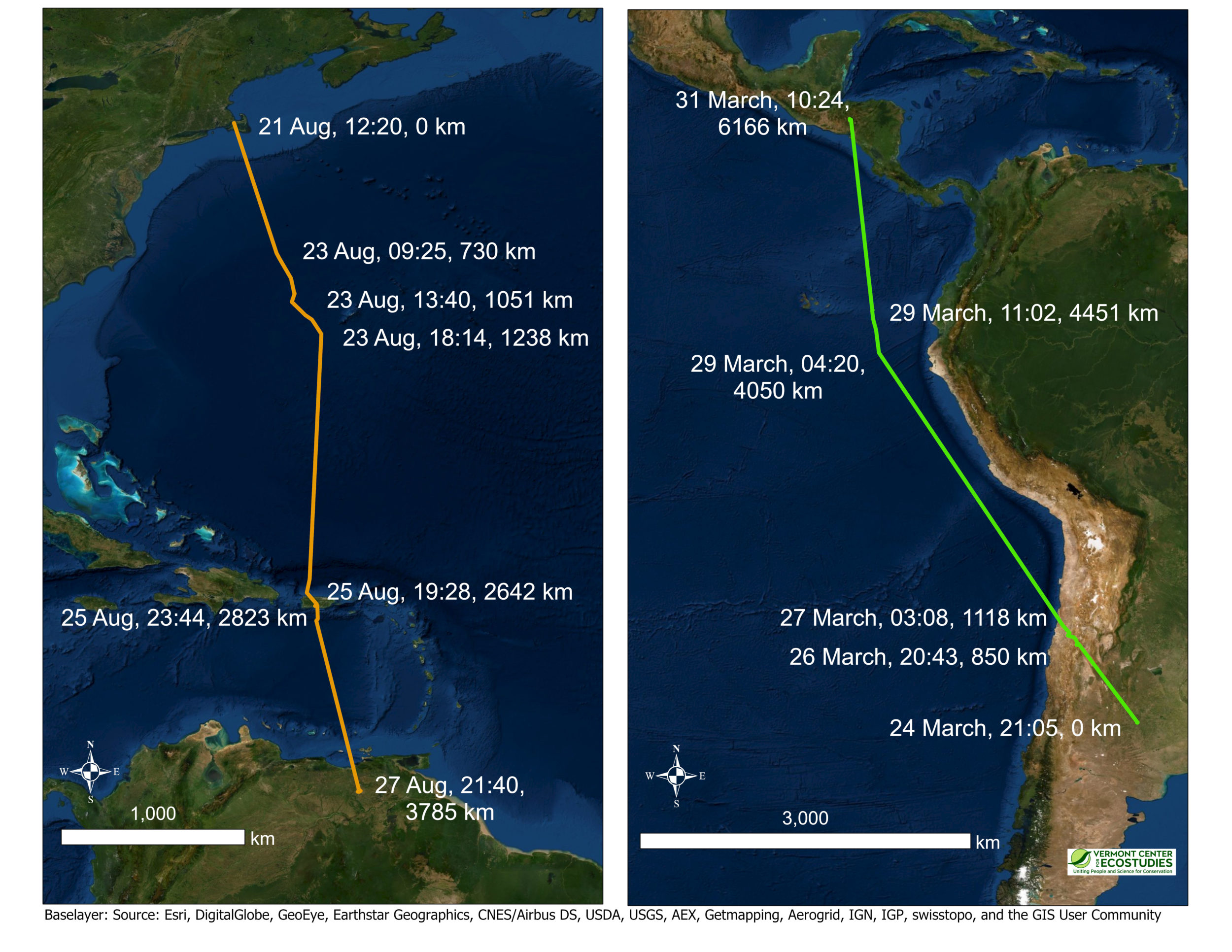

Two examples of migratory segments illustrating nonstop flights over long distances for multiple days by Upland Sandpipers wearing satellite tags. Extreme migratory movements included a southbound flight of 3,785 km in a 6-day period over the Atlantic Ocean from Massachusetts to Venezuela (left panel), and a northbound flight of 6,166 km in a 7-day period across the Andes and along the Pacific coast from Argentina to Honduras (right panel). Annotated values for a subset of fixes in the figure include the date, time (in UTC), and the cumulative distance traveled (km).

In a first for this species, our team (myself, former VCE biologist Rosalind Renfrew, and Brett Sandercock of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, in Trondheim, Norway) used lightweight satellite tracking tag data (and some complicated math) from nine Upland Sandpipers to describe a series of new discoveries.

We learned that sandpipers regularly crossed major ecological barriers during migration, which included long oceanic flights, high elevation mountains, and tropical forests. We documented new staging sites at canefields in the mountain valleys of Colombia, grasslands in the Llanos of Venezuela, and at airports (e.g., Baltimore Washington International Airport, Maryland) along the Atlantic Coast of the U.S. Unlike many bird species who overwinter in a single location, individual Upland Sandpipers used multiple discrete areas up to 1,500 km apart on nonbreeding grounds. In one instance, a sandpiper tagged in Massachusetts overwintered in Brazil less than 100 km away from another sandpiper tagged in Kansas; and two sandpipers that were captured 27 km apart in Kansas overwintered ~2,600 km apart from each other in central Brazil and Uruguay.

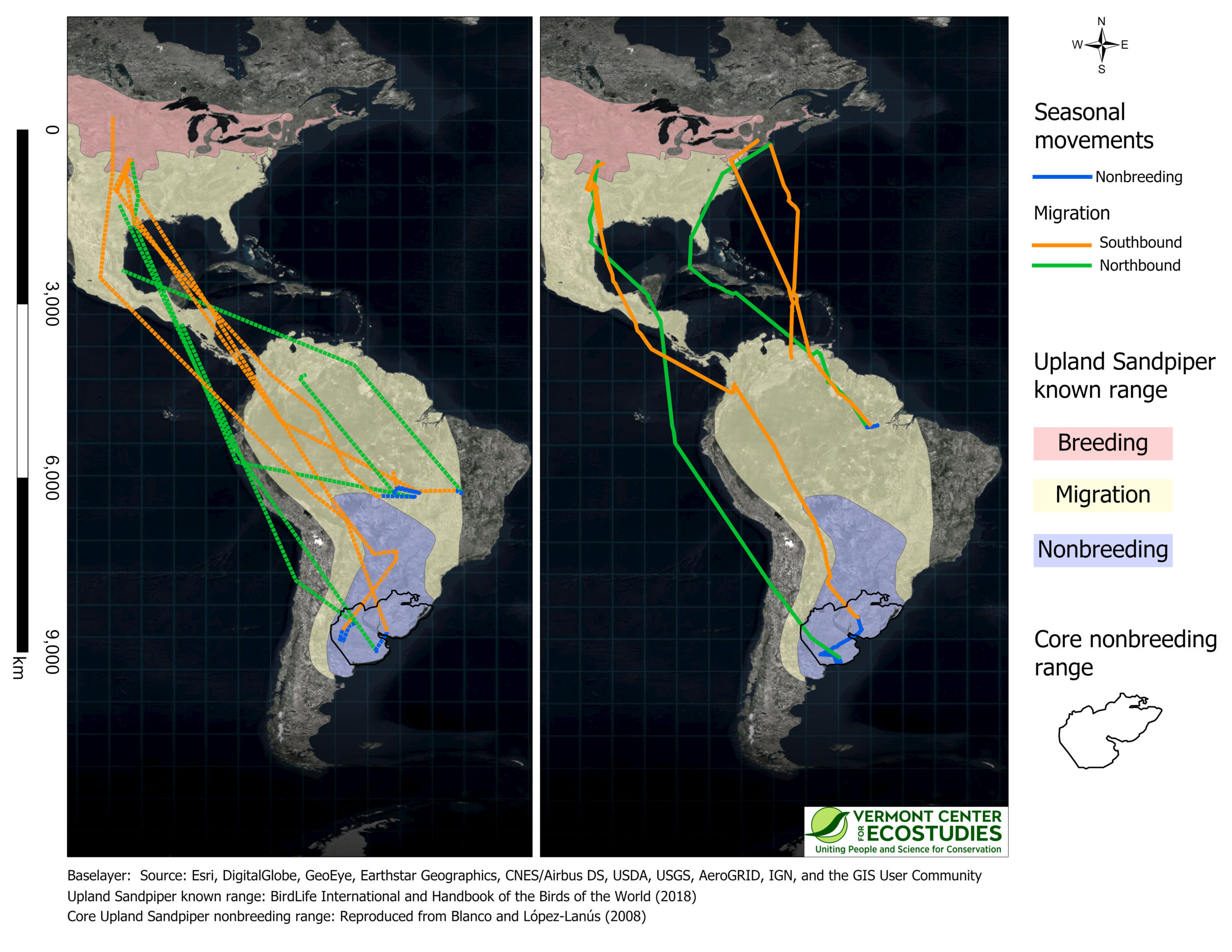

The annual movement paths of nine Upland Sandpipers captured in Kansas or Massachusetts and tracked with GPS (left panel, dashed lines, 5 birds) or solar-powered PTT tags (right panel, solid lines, 4 birds). Movement paths include southbound migration in autumn (Aug-Nov, orange), winter movements (Dec-Feb, blue), and northbound migration in spring (Mar-May, green). Colored semi-transparent polygons are the known breeding, migration, and nonbreeding range of Upland Sandpiper from BirdLife International and Handbook of the Birds of the World (reproduced with permission). The core nonbreeding range (black polygon, both panels) represents the area that is considered to have the greatest density of Upland Sandpipers on the nonbreeding grounds (reproduced with permission from Blanco and López-Lanús, 2008; http://lac.wetlands.org/Publicaciones/Nuestraspublicaciones/tabid/3079/mod/1570/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/2245/Default.aspx).

Perhaps the most dramatic discovery, however, came from the Amazon rainforest. I don’t think anyone, including us, would have confidently predicted what we discovered: some of these Upland Sandpipers—a species thought to inhabit large open grasslands exclusively—spent the nonbreeding season on partially flooded river islands in the Amazon basin! Just as extraordinary, this area is almost 1,000 km north from the nearest site previously known to host overwintering Upland Sandpipers. Taken together, we hope this suite of discoveries moves the needle forward substantially in terms of adapting and improving the global conservation strategy for this shorebird species.

The full article, “Migration Patterns of Upland Sandpipers in the Western Hemisphere,” is freely available on the Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution website. In addition, all of the raw and processed tracking data are freely available for the public to view, and other researchers to use, at Movebank.org.

Funding for this research project was provided by the U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program (Project 15‐764).

I don’t know which is more amazing, the feat of the Upland Sandpipers or the feat of the scientists. How wonderful it would be if all around the world, citizens celebrated what we can learn about the other living creatures around us. Thank you!

Many thanks! I can say with confidence, that the birds do the hard work. 😉 The satellite tags that are currently available do not reliably record flight altitude, but that would have been great to document. We have good evidence from other shorebirds that flight altitude during those long overwater journeys can be as high as 15,000 feet or more. The birds also likely rotationally shut down (i.e., rest) part of their brains while flying for many days on end–there’s more and more evidence that migratory birds (like whales and dolphins) do this. Wonderful stuff.

Any info or insights on whether Upland Sandpipers migrate individually or in flocks?

Very impressive information! Great work to continue with!

Good question. We don’t know for sure, but I’ll take a guess and lay out my logic. The Upland Sandpiper populations in the northeastern US/southwestern Canada are much smaller than populations throughout the rest of their range (e.g., the northern Midwest and the Canadian prairie pothole region). In our study, birds from the east of the range traveled through Florida or the Caribbean during migration. On eBird, the vast majority of Upland Sandpipers observations in Florida and the Caribbean are of lone birds migrating through. In contrast, eBird observations from Texas and Central America (where our Midwestern birds migrated through) are not often of just 1 bird–those reports are generally of 4-10 birds…sometimes much larger. My interpretation of this observation pattern is that Upland Sandpipers most likely fly solo, and that you see groups of sandpipers in Texas and Mexico during migration b/c multiple sandpipers happened to stopover in the same place/patch of grassland. Remember, the population size of Upland Sandpipers passing through Texas/Mexico is many many times larger than the population size of Upland Sandpipers passing through Florida/Caribbean so you’d expect these chance meet-ups. If they migrated in small groups regularly, I would expect many more observations of more than one sandpiper during migration in Florida and the Caribbean (even with the relatively small population size of this species in the NE US and SE Canada).

Another line of reason: we documented extremely weak migratory connectivity in our study for Upland Sandpipers. For example, we tagged two Upland Sandpipers on their breeding territories in Kansas, just 17 miles apart. Those two birds overwintered >1600 miles apart in South America and took different routes through Central America even. Similarly, two birds that we tagged in Massachusetts spent the winter ~675 miles apart in South America. The bottom line: if you’re an Upland Sandpiper, then you probably don’t want to follow any other Upland Sandpiper during migration–they’re likely not going to the same place as you!