Norwich, Vermont – Mountain Birdwatch data lie at the heart of a published study revealing that continent-wide bird surveys may offer important conservation insights, but they can miss rare or isolated species whose habitat lies off the beaten path, such as at high elevations or in remote bogs. The study, led by avian ecologist Joel Ralston and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, in close collaboration with VCE’s Judith Scarl and Dan Lambert, reports how combining data from point counts across the landscape can elucidate how birds in difficult-to-reach habitats are faring.

Their analyses of data from 16 point count programs conducted in spruce-fir forests across the Northeast and Midwest show that populations of four species considered ecological boreal forest indicators — Bicknell’s Thrush, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, Magnolia Warbler and Blackpoll Warbler — are in significant decline. Two other species, Gray Jay and Evening Grosbeak, previously believed not to be of conservation concern, also showed significant declines.

“This is the first time anyone has combined local point count data from several different sources to estimate population trends at a larger spatial scale for these spruce-fir forest-dependent species. This is the first time we have a regional look at trends in this group of birds,” says Ralston. Details appear in the current issue of Biological Conservation.

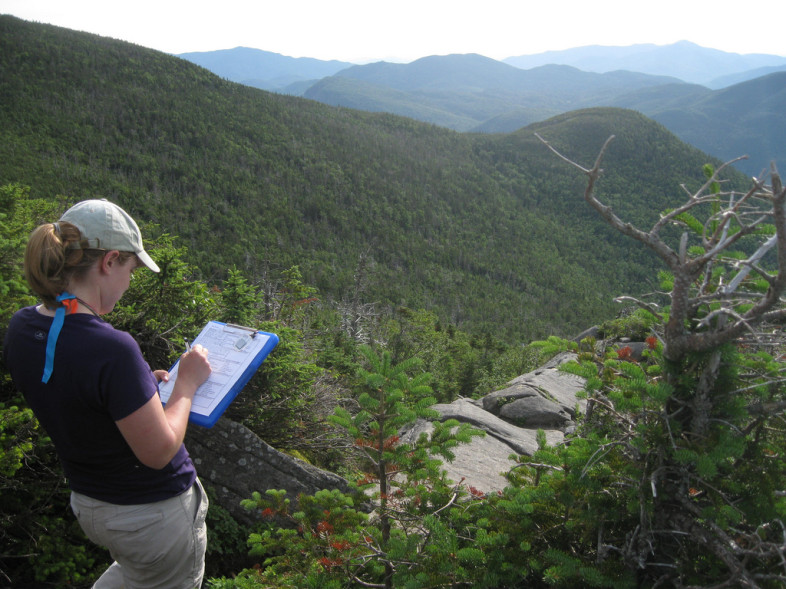

“Anyone who has hiked, waded, climbed, or trudged through spruce-fir forests can understand the challenge of trying to survey these birds,” says VCE’s Scarl. “Yet understanding population trends across this broad region is critical for conservation.”

As VCE and our Mountain Birdwatch volunteers know well, habitat specialists like Bicknell’s Thrush are poorly monitored in continentwide survey programs like the Breeding Bird Survey and National Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, because they inhabit places where few observers venture. For example, the Breeding Bird Survey covers roadside habitats, Ralston says, “but the birds we wanted to study don’t usually live by roads. They live in remote bogs, in thick, hard-to-penetrate spruce forests and on tops of mountains.”

Although regional monitoring programs like Mountain Birdwatch have been conducted for years, or even decades, in these areas, the information had never been compared across surveys or regions.

For this study, the researchers identified point counts conducted between 1989 and 2013 in spruce-fir habitat in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Maine, New York’s Adirondack and Catskill Mountains, Vermont’s Green Mountains, and New Hampshire’s White Mountains. They included counts that could yield at least eight years of data. They identified 14 bird species as either obligates, i.e. those that nest only within spruce-fir forests, or associates, those that prefer spruce-fir but can use other forest types.

In combining these data, the researchers controlled for differences in how surveys were conducted, and they calculated detection probabilities to estimate population trends for 14 species. When possible, trends were estimated separately for each species in the Northeast, in the Upper Midwest and across the entire study region.

Results showed that seven, or 50% of the species, had experienced significant declines: Olive-sided Flycatcher, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, Gray Jay, Bicknell’s Thrush, Magnolia Warbler, Blackpoll Warbler, and Evening Grosbeak. Five others had significantly increased: Red-breasted Nuthatch, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Swainson’s Thrush and Palm Warbler.

Lambert notes, “In the Northeast, we’ve been concerned about boreal lowland and mountain birds for many years. These results challenge us to develop new strategies to stem the decline of spruce-fir birds within and beyond our region.” The authors point to factors such as pressure on spruce-fir woodlands from commercial forestry, human-centered development, insect pest outbreaks, and climate change as worrisome hurdles for spruce-fir specialist bird species.

This study should be particularly valuable to conservation managers by enabling them to examine the data from multiple angles, including the overall picture for each species, by region, or within a single local survey. Ralston notes, “We hope the methods we’ve introduced are useful to our colleagues concerned about spruce-fir birds, but also to anyone studying any type of rare community requiring management and conservation.”

It can be important for managers to assess data by region because there might be places where a species of concern is not declining, Ralston points out. “You can pick those out from our results, and local managers really need that information.” For example, the analysis did not find any birds declining in high-elevation habitats in the Adirondack and Catskill mountains. “Even birds declining regionally seem to be doing OK there,” he says.

An example is the Swainson’s Thrush, which is declining across the U.S. according to national surveys such as the Breeding Bird Survey. However, Ralston and his colleagues found that high-elevation populations in the East are significantly increasing. He explains, “We think it’s because this species is moving up the mountain slopes. Scientists at the Vermont Center for Ecostudies have been noticing more and more Swainson’s Thrushes in their high-elevation surveys in recent years, and our results support their local observations at a regional scale. National surveys that don’t sample high-elevation forests have missed this.”

Overall, the study highlights the need for more formal monitoring in rare and inaccessible habitats. Coauthors with Ralston include UMass Amherst scientists Bill DeLuca and David King, Gerald Niemi of the University of Minnesota Duluth, Michale Glennon of the Wildlife Conservation Society, and Judith Scarl and Daniel Lambert of VCE. This work was funded by the Northeast Climate Science Center at UMass Amherst, which provides scientific information to help land managers effectively respond to climate change.

Contact:

- Chris Rimmer, Vermont Center for Ecostudies, Executive Director, 802-649-1431 x1,

- Joel Ralston, 413-545-2665,