The Migratory Bird Treaty Act and bird conservation

Snow Buntings in flight.

Last December, a team led by scientist Tatsuya Amano from the University of Oxford’s Conservation Science Group published an important paper on waterbird conservation. Using data collected across the globe, they examined population changes over the past 3 decades in 461 species of waterbird, including everything from ducks to shorebirds to flamingos. During this time, waterbirds in some parts of the world thrived, but in other places they experienced steep declines. When the scientists looked for an explanation for this pattern, they were able to isolate two key predictors of whether waterbird populations shrunk or grew.

Predictably, the loss of surface water explained some of the decline in waterbird numbers. Central Asia, for example, has lost vast amounts of its surface water due to drought, diversion and damming of rivers, and unregulated water withdrawals for human use; waterbird populations in this part of the world declined steeply. This makes sense: without surface water, these species have no place to live.

Surprisingly, more important even than the loss of surface water was the role of effective governance. Waterbirds declined significantly in countries with weak or ineffective governments, but their numbers grew in countries that were politically stable and well-governed. The overall effectiveness of a country’s government, quantified annually by the World Bank, includes a variety of factors like regulatory quality, rule of law, control of corruption, and accountability, but the most likely link between waterbird population health and governance is through the environmental aspects of governmental regulation. When countries have well-enforced environmental rules and high levels of investment in conservation, waterbirds – and presumably other wildlife – thrive. For example, Iran, with weak regulation of hunting and limited protections for wetlands, saw substantial declines in waterbirds. During the same time period, waterbirds thrived throughout the countries of the European Union, where protections for birds and their habitats are stringent.

Coincidentally, two days after this study of waterbird populations was published, the US Department of Interior announced that it would no longer strictly enforce the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, one of our oldest and most important environmental laws, and one of the few that specifically protects birds.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act was originally enacted in 1918 to implement a convention on bird conservation between the US and Great Britain, acting as the sovereign of Canada. The Act was later amended to implement conventions with three other nations that share bird populations with the US: Mexico, Russia, and Japan. Enacted at a time when bird populations faced devastating threats from commercial hunting, the intent of the law was clear: to promote bird conservation by prohibiting the unregulated killing of wild birds. Although clearly motivated by the wanton slaughter of birds taking place at the time, the language of the Act itself is general. Simply put, except as otherwise expressly allowed, it is illegal, “at any time, by any means or in any manner”, to kill any bird that is protected under the Act or to take its nest or eggs.

The Trump administration prefers a different interpretation. According to its memorandum, the Department of Interior now views only those actions “that have as their purpose the taking or killing of migratory birds, their nests or their eggs” as violations of the Act. In other words, only actions intended to directly kill birds count as violations of the Act. This upends the interpretation that has been held by every prior administration in recent history – Republican or Democrat – from Richard Nixon to Barack Obama, which was quite simple: the Act prohibits the unregulated killing of birds, whether the intent was to kill them or not.

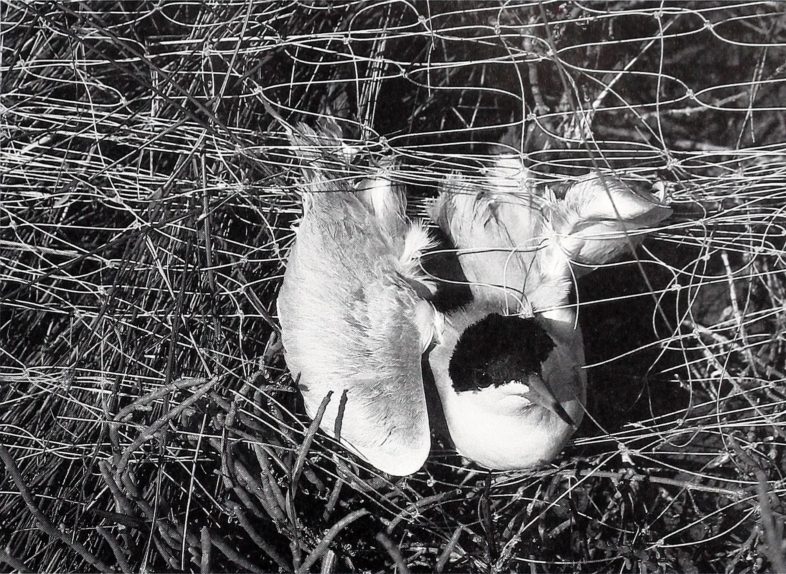

This is not a picayune distinction. Market hunters and milliners are no longer the preeminent threats to bird populations in North America. Outside of the closely regulated and sustainable hunting of game birds, most human-caused bird deaths in the US are inadvertent. Each year we unintentionally kill hundreds of thousands of birds when when they are poisoned by pesticides or in tailing ponds at mines or oil wells, when they collide with wind turbines or communication towers, or when they are caught accidentally in gill nets. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act has been the only tool to address these important but otherwise unregulated sources of mortality, and now even that modest bastion of regulation looks to have fallen by the wayside.

A Forster’s Tern accidentally entangled in fishing net. From the article “Hope for Migratory Sea Birds” by Cynthia Henderson Vega, which appeared in the Winter 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

The Department of Interior relied in part on judicial uncertainty to justify its reinterpretation of the Act as a prohibition only on illegal hunting and unregulated oology. And indeed, courts have long split on how to interpret the meaning of the statutory language. Some have held that the Act applies to any activity that results in the killing of birds, whereas others have held that the Act only applies when birds were intentionally killed.

Yet the Act has been a successful tool for bird conservation despite this uncertainty. In a remarkable letter, 17 former high-level Department of Interior officials, including political appointees from the Obama, Clinton, and George W. Bush administrations, wrote Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke encouraging him to reconsider this policy. As they put it, the Act “can and has been successfully used to reduce gross negligence by companies that simply do not recognize the value of birds to society or the practical means to minimize harm. Your new interpretation needlessly undermines a history of great progress, undermines the effectiveness of the migratory bird treaties, and diminishes U.S. leadership.”

Under previous administrations, the Fish and Wildlife Service, empowered by a commitment to conservation at the highest levels of government, used the Act to signal the seriousness with which they viewed any activity that led to death of birds. Industries whose activities threatened bird populations – oil and gas, fishing, coal, wind and solar power, and electric-transmission utilities, to name a few – understood the rules and, as a result, acted proactively to take measures to minimize the risk that they would, in the course of carrying out otherwise-legal business activities, kill birds.

With the Trump administration signaling its lack of interest in holding industries accountable for causing unnecessary bird deaths, little incentive exists for maintaining the common-sense conservation measures that previous interpretations of the Act required. Oil producers working to keep migratory birds away from toxic tailing ponds or wind-power companies that shut turbines down during peak bird-migration times may see no reason to continue these activities. Commercial fishing fleets need no longer worry about solving the problem of seabirds drowning in nets or on baited lines. One of my first jobs out of school involved helping engineering firms to comply with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act during the construction of bridges and roads, which generally involved things as simple as waiting to tear down an old bridge until Cliff Swallow colonies had fledged their young. Now, even minor acts of conservation like this will be harder to come by.

Cliff Swallows nesting beneath a bridge in North Carolina. Photo by Ken Thomas (kenthomas.us).

Given the scope and breadth of the Act, the significance of the recent change in interpretation by the Trump administration is not easily overstated. The Act currently affords protection for more than 1,000 bird species, including every species native to the US. Indeed, it is the only legal protection for most of them; unless a bird species is otherwise specifically protected by law – for example by the Endangered Species Act or the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act – then regulations promulgated under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act represent their only formal line of defense. This would include almost any bird that you’ve seen in Vermont in the past year: Hermit Thrush or Scarlet Tanager, Tree Swallow or Chimney Swift; none are specifically protected by any Federal law save for the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Hermit Thrush, our state bird, is one of many species protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

As we know from the Tatsuya Amano’s work on waterbirds, and from our country’s own history of successes and failures in bird conservation, weak or inconsistently enforced laws and stingy investments in conservation will eventually lead to the demise of wildlife populations. Unfortunately, we appear well on our way to meeting both of these conditions. Federal and state investment in conservation in the US has declined sharply over the past decade (for example, see here or here) and, with the decision to weaken the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and similar efforts targeting the Endangered Species Act, we are poised to enter an era of in which environmentally damaging activities will no longer face strict regulation.

The US Congress enacted the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918 as a response to our collective failure to regulate our own worst behaviors, and in doing so created the conditions that allowed for one of the great conservation success stories of all time. Now, in the form of a 41-page memorandum, we face a failure of governance that may undo many of the gains we have realized in bird conservation. What’s more, we risk these gains for no good reason: the change in policy is a solution in search of a problem. For decades, administrations of all political stripes have found ways to balance the needs of people and of birds within the broad outlines of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Abandoning the principles of conservation enshrined in the Act will benefit few, if any, people, but will surely come at a cost to the birds that we all cherish.

Unless and until we are rid of Trump there is no hope of his growing a frontal cortex. The most effective way to restrain business-for-profit that imperils migratory birds is surely limited to direct action against the malefactors themselves. Birders, one thinks, are better organized than many other interest groups concerned with the natural world and ought to attempt boycotting where feasible in birds’ defense and cry for the pangolin. Peter Wackell

It amazes me that any country can be quite so cavalier about its international treaties, as the USA.

It is a very sad reflection on the times in many ways. Particularly so if we consider that the treaty is 100 years old. We have hardly progressed since, and now this is a huge step backwards. It really speaks volumes about our collective inability to rise to the challenges of the twenty-first century – biodiversity collapse and climate change.