Morning view from The Putney School © Kevin Dernier

My day of bird banding starts at 3 a.m., when I wake in my tent, quickly dress in my heavy field clothes, and drive to the field site, parking far away so the birds don’t know I’ve arrived.

Weaving through the thorny Multiflora Rose, I open the mist nets one by one. Last night’s rain, another torrential downpour in a resoundingly wet summer, has drenched the vegetation. And now I’m also drenched from the waist down.

It’s time to set the bait. Quietly, and with practiced movement, I duck under wild grapevines and skirt around rosebushes. I place my speaker at the foot of my most promising net, wedged in a section of habitat where, while scouting, I’ve seen my target move through. I retreat a distance and activate my lure, and the speaker begins to chirp, warble, and meow.

It doesn’t take long before the male arrives to investigate. He skitters up a branch on the opposite side of the net from the speaker, getting the height advantage before he glides over my net to find the intruder. My target follows her mate across the gap, but her approach is lower and she meets the net, falling into one of its pockets. I spring from my hidey-hole and make my way to her. Two days of unsuccessful netting have finally paid off: I have my target.

Jack Maynard 2023 via Macaulay Library, ML611275322

This female Gray Catbird is one of many breeding in the dense, shrubby landscape of The Putney School in Putney, Vermont. She likely arrived here in early May, paired up with her mate (which I caught weeks earlier), and—judging by her fluid-filled brood patch—has an active nest. While I wish I had caught her sooner, she is exactly who I was hoping for.

At my banding station I give her a unique set of color bands to distinguish her from the other banded catbirds on the plot. I also make her a custom harness for a radio transmitter. She is the tenth female I’ve tagged for my study, and thankfully, I will never need to recapture her to get the data I need. As dawn breaks, I pack up and set off for some well-earned coffee at the Putney Diner.

Banded and female Gray Catbird © Kevin Dernier

In the past, VCE researchers have used the same type of radio transmitter and others like it to study the migratory movements and territory sizes of birds using radiotelemetry, a method of tracking radio signals emitted from a transmitter on an animal. Tools like Motus Wildlife Tracking Network can simplify this work by creating a standardized system of receiver towers to detect the large- or small-scale movement of animals on the landscape.

Kevin Dernier with a fledgling Gray Catbird on the Putney campus © Kevin Dernier

I’ll be evaluating whether this technology can serve a new purpose: studying behavioral patterns. Specifically, I’m testing whether automated radiotelemetry can be used to collect fine-scale data on how female songbirds spend their time during the breeding season. Under the mentorship of VCE Conservation Scientist Dr. Desirée Narango, I am collaborating with The Putney School, which hosts a Motus receiver on campus, to study the catbirds nesting on their property.

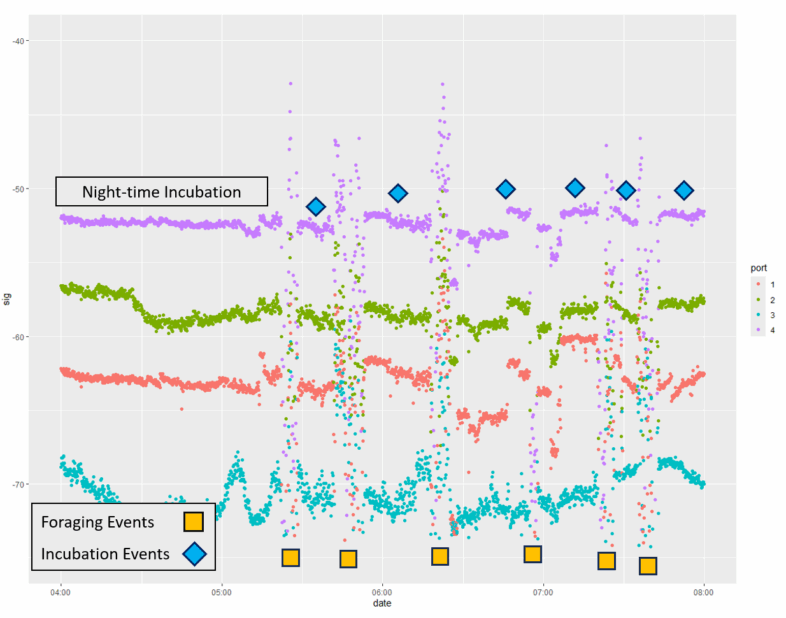

This research takes advantage of a simple principle of radiotelemetry: A receiver will detect the transmissions from a radio transmitter on a bird and record how ‘strong’ the signal is of each detection. As that bird moves around the receiver, the signal strength will be highly variable as the bird moves closer, further, or changes its orientation. When the bird is holding still relative to the receiver, the signal strength of each detection will remain fairly constant. In effect, we can study how much time birds spend “active” and “inactive” by looking at the patterns in variation of the signal strength.

Detection signal strength over time for tagged female GRCA 189 on June 22nd, 2025.

This method has been previously used to study the activity patterns but not the breeding behavior of migratory songbirds. I’m testing whether we can quantify the time a tagged female is sitting on her nest versus actively foraging, by looking at the same patterns in signal strength variation. To do this, I find catbird nests and set up cameras to monitor nest behavior. I’ll then compare the ‘true’, video-recorded behavior of the female with the estimated periods of inactivity from the telemetry receiver.

At the same time, I’m interested in using this method to better understand how Vermont’s summer weather patterns, like high rainfall or hot temperatures, might affect female behavior. For example, during high rainfall events, a female may spend more time protecting her young than feeding herself, to avoid exposing the young to cold and wet conditions. This summer has had some pretty significant fluctuations between periods of rain and dry, and hot and cold, providing ample variation to see how females adjust their behaviors.

As any mother could attest, reproduction tends to be much tougher on females than males. In birds, the energetic and nutritional cost of forming eggs, keeping them warm, and then feeding the hatchlings until they’re fledged and fending for themselves is already incredibly high, even with the male pitching in. When you throw extreme weather into the mix, her parental instincts may drive her to sacrifice even more time she could spend foraging in her short breaks off the nest towards keeping eggs warm and dry. So it’s possible the extremely wet spring and summer we’ve had so far may cost the female birds, which could ‘carry over’ to other stages of the annual cycle, like migration. But the first step is determining how to track the behavior of these skulky, secretive birds.

Gray Catbird female incubating her eggs– collected during trial for this study. I will compare the time female catbirds spend on the nest in our videos to the time estimated from the telemetry detections.

My hope is that this study will provide another tool for avian ecologists studying reproductive behavior. With luck and persistence, we may one day be able to piece together how the reproductive burden affects females season-to-season and year-to-year, and devise management practices that address the impact that severe weather events could have on them.

Acknowledgements: This research project is made possible with generous funding from the Wilson Ornithological Society and the VCE Peter Brooke Explorers Fund.

This article offers a fascinating glimpse into the meticulous process of bird banding and the innovative use of technology to study bird behavior. The authors passion for wildlife research is truly inspiring!Mercury Coder

This article offers a fascinating glimpse into the meticulous world of bird research, blending personal dedication with cutting-edge technology. The authors passion for tracking Gray Catbirds is palpable, making complex scientific work accessible and engaging.