By: Desiree Narango and Kevin Tolan

This week, Mansfield’s toll road parking lot was filled to the brim with assistants and volunteers. Besides ourselves, other VCE affiliates included Chris Rimmer, Melory Brandao, Natalie DeVito, Nathaniel Sharp, VCE interns Emily, Julia and Pablo, VCE ‘tick team’ technicians Hannah and Amber, and VCE Executive Director Susan Hindinger. Other visitors included a budding 11-year-old birder who came to see bird banding for the first time and Desiree’s son Finnley, who tells us his favorite bird is the American Robin. It was a beautiful night under the stars for camping and excellent weather for fieldwork.

VCE interns enjoying the Mansfield views (Photo: © Emily Marple)

This week marked the beginning of a very exciting time of the summer–when we start catching fledgling baby birds! These birds are more accurately referred to as juveniles (or hatch-years, i.e., hatched this year) as they have fledged the nest and are now learning how to forage on their own. The team was excited to find this older juvenile Hermit Thrush in the nets, who was likely born much farther down the mountain but had adventured up to the alpine ridge in its travels. We caught hatch-year birds from several resident and short-distance migratory species, like Dark-eyed Juncos (4), a Purple Finch (1), and lots of species like White-throated Sparrows and Golden-crowned Kinglets carrying food, meaning fledglings from some of our longer migrating species are not far behind.

Hatch-year Hermit Thrush (i.e., an individual born this year) (Photo: © Michael Sargent)

| Species | Individuals |

| American Robin | 1 male |

| Bicknell’s Thrush | 3 females and 16 males |

| Blackpoll Warbler | 4 females and 4 males |

| Chestnut-sided Warbler | 1 female |

| Golden-crowned Kinglet | 2 females |

| Hermit Thrush | 2 hatch-years |

| Least Flycatcher | 1 female |

| Magnolia Warbler | 1 female |

| Myrtle Warbler | 4 females and 9 males |

| Purple Finch | 1 female and 1 hatch-year |

| Slate-colored Junco | 2 females, 3 males, and 4 hatch-year birds |

| Swainson’s Thrush | 2 males |

| Winter Wren | 2 males |

| White-throated Sparrow | 3 females and 10 males |

If you’ve been following VCE’s work over the past few years, you may be familiar with our three-year effort to research the late-winter and early-spring movements of BITH using GPS tags–high-tech bird ‘backpacks’ that track movements with a high level of precision. Although the primary time period of interest is March through May, we’ve also gotten a unique look into the migratory connectivity of these individuals or how the population links across time and space. The Mt. Manfield population displays a very high level of migratory connectivity, with the vast majority of individuals overwintering in the Dominican Republic, some only several kilometers apart. The tag data also places most individuals in the mid-Atlantic region on October first and/or October 15th. They also usually arrive at their winter territory before November first. This piece of the puzzle is critical to successfully conserving migratory birds, but it can also be one of the most elusive pieces of data to get.

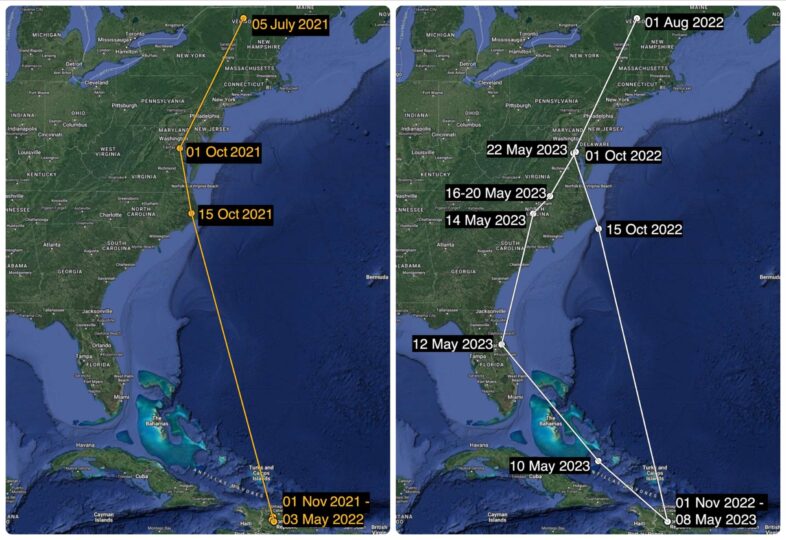

Two consecutive years of GPS data from female Bicknell’s Thrush #2821-7910, who currently holds the record for the highest elevation, documented Bicknell’s Thrush during the winter season at ~2,500 meters above sea level. (Note: migratory pathways between points are assumed and not actual tracking data).

This was a successful week for our GPS study. Between Tuesday and Thursday, we recovered 3 GPS tags (although only one unit yielded “good” data). Despite the small number of GPS tags we’ve managed to deploy on females, we recaptured a familiar face that some readers may remember from a 2022 blog post: female #2821-7910. In 2022 she set the record as the highest elevation Bicknell’s Thrush we’ve ever documented, so we were ecstatic to have recaptured her for the third consecutive year with an incredible 60 GPS fixes stored on her GPS backpack! Having two consecutive years of high-resolution spatial data gives us a special look into her nonbreeding behavior. She was near Washington D.C. on October first in 2021 and 2022, actively migrated on October 15th, and returned to her high-elevation winter territory by November 1st. In 2022 she was on her territory until the GPS battery died on May third, but the longer-lasting battery in 2023 shows that she moved off territory on May eighth or ninth before moving north through the Bahamas and Florida.

Young (Second-year) male Bicknell’s Thrush with a Motus Nano Tag (left) and After second-year male bird with a GPS tag (right). You can tell the bird on the left is a young bird by the pale streaks on its greater covert feathers in the wing. (Photo: © Michael Sargent)

As exciting as recapturing this female is, there’s still much work to do in deciphering a missing chapter of the Bicknell Thrush life cycle–what are females doing? So far, most (but not all) of the tracking tags deployed on Bicknell’s have been on males, primarily because they are much more abundant in our male-dominated population (depending on the year, there are roughly 2.5 males for every female), and males respond more aggressively to playback. This is reflected in our captures this season: 77 males but only 10 females! This sort of ‘male-biased’ research is widely common in ornithology, meaning conservation decisions could be potentially geared toward the habitat needs of just males instead of being inclusive toward both males and females.

The sun sets on Mount Mansfield (Photo: © Emily Marple)

Fortunately, new funding secured by Bicknell’s Team 2.0 (composed of many members of the VCE team) will further advance our Mansfield research by implementing a new spin to the research: focusing on the full annual life cycle ecology of female BITH. In 2024 we’ll focus our efforts on studying female survival, migration, and habitat selection on the wintering grounds to fill gaps in their conservation, such as what aspects of land use and global climate change might be driving declines and limiting populations of this sensitive alpine bird.

One of the technologies we’re using is Motus tags, which we are deploying on young birds and females to provide a better understanding of the migratory behavior and timing of these understudied individuals. This past winter, a team from VCE traveled down to the Dominican Republic and deployed 21 “nanotags” on unsexed Bicknell’s. Motus tags are automated radio telemetry tags that last multiple years and can provide information on the movements of birds throughout the annual cycle without the need to recapture. A network of towers hosted by universities, schools, non-profits, and private landowners worldwide provides data on where birds are migrating by detecting the radio tags and submitting their data to the centralized Motus network. In the next few years, we will be deploying more Motus tags on breeding females to provide essential data about when they arrive to and depart from Mansfield, daily activity, and fall and spring migratory pathways. Importantly, these tags will also help us estimate where survival is lowest since data recovery is not solely dependent on birds surviving their return migration to Mansfield for recapture. Stay tuned for new insights as we dive into the ecology and conservation of female birds.